This year we commemorate the 76th anniversary of the battle of Greece and Crete in 1941. The struggle against the German invasion was fought over the length and breadth of the Greek mainland and on to the fateful defence of Crete. One of those thousands of diggers was Richmond’s Bernard O’Loughlin. This is the story of Bernard and some of his comrades who fought in Greece and escaped – Bernard to Crete – and the brave Greek locals who aided him.

Across the length of Greece and on to Crete, the end of battle would often lead to capture. But for many – indeed hundreds of Allied soldiers – defeat would be followed by a successful evasion from capture – and a return to Allied lines on Crete, or to the Middle East.

These escapees wrote later of the generous and brave help they received from the ordinary people of Greece, a help essential to their escape. This is the story of four escapees from Corinth and the Argolid in the weeks following the battle of Corinth Canal on 26 April 1941.

Some, like the former New Zealand shepherd 24-year-old Corporal Fred Woollams of the New Zealand 19th Infantry Battalion, who had taken part in the battle of Corinth Canal and successfully made his escape eastwards – would encounter many colourful and brave characters on his journey to evade capture.

He was once helped by a friendly Greek mountain shepherd in the hills north of Megara. His name was Panayioti but Fred called him Pete. Despite speaking little English, Fred wrote that: “He talked all the way, but we understood very little, except when his words were made plain by gestures; he did not seem to mind whether we answered him or not …”

Taken to his small hut in the mountains where the poor Panayioti lived with his family, Fred and three other comrades were fed “beautiful brown bread”, “white goat’s milk cheese” and milk. Later they would enjoy olives and “a huge wicker-covered bottle of wine.” For breakfast Fred enjoyed a meal of milk, cheese, bread and tomatoes. This brave man and his family and friends would hide Fred and his friends for three months. On another occasion Fred was walking in the direction of Loutraki when he came across another helpful shepherd. He described the shepherd in terms that will be familiar to many: “He was dressed in native costume – a bluish smock and pleated skirt, and long white stockings. Below his knees were black garters and on his feet, not the national shoe, but one with rubber soles. Girded round his waist was a wide leather belt, a pouch, and a huge sheath knife.”

These were just two of the many locals of the region who would hide and look after Fred – despite the reality of German retribution – for more than 20 months.

Prior to his capture in 1942, Fred would enjoy many lively local celebrations – even a wedding – in his mountain hide-away. As he enjoyed tucking into some of the wedding food, he was amazed when the wedding party began firing off their weapons in celebration – and all in occupied Greece!

It is no surprise that Fred dedicated his memoir Corinth and All That to both his comrades and to those who helped him: “to the men who fell at Corinth … [and] to those Greek people who, at the risk of their lives, sheltered Allied soldiers.”

One Australian soldier – Private George Smith of the Australian 2/6th Infantry Battalion – would live to tell one of the most amazing stories of escape. Separated from his unit before the battle of Corinth, George was wandering the Greek countryside north of Corinth when he had a strange encounter. Taking to “the bush” as he said, George met up with a “Greek chappie” as he wrote: ” … he could speak English. He said to me ‘You remember Young and Jacksons?’ I said I did and he said ‘Well, that’s where I want to get back to, to Melbourne … during this war I came over for a holiday and got caught up … and now I’m trying to get back.’ He said he knew how to get to Crete. He kept me under cover. His people had some land, and he knew some hiding places … He got hold of a small boat …”

And the rest – as they say – is history. George, with the aid of his new Greek Australian comrade made it to Crete and safety.

The story of two other diggers who escaped was told by Australian war correspondent and poet Kenneth Slessor in the pages of the Melbourne daily newspaper The Argus on the 26 May 1941. He had interviewed these men in Egypt after their successful escape from capture at Tolo.

Australians Major Bernard O’Loughlin of the 6th Division and Captain Henry Bamford of the 2/3rd Infantry Battalion had been responsible for organising the dispersal of Allied troops awaiting evacuation at Nafplio and Tolo to assist in the smooth operation of their evacuation.

As the Germans approached Tolo on 29 April many of the exhausted troops resigned themselves to captivity. Bernard and Henry decided to make a run for it and had made off into the hills surrounding Tolo and headed east.

The 36-year-old Bernard was from the inner Melbourne suburb of Richmond. The only son of Mr and Mrs James O’Loughlin of Waltham Street in Richmond, he had been educated at St Ignatius. Before enlisting, he worked as a law clerk in a solicitor’s office in Bourke Street, Melbourne. Twenty-four-year-old Henry was from Bowral in New South Wales.

Bernard would describe his 15 days on the run and at sea as being “hunted like animals”, in a game of “perilous hide and seek” that he would remember as “the most intense of his life”. Bernard’s escape would lead to him being Mentioned-in-Despatches.

Essential to their survival was the advice and aid from the locals. Soon after leaving Tolo they were advised to head to what he called the village of Krindion, most likely modern day Kranidi, the modern day home of James Bond (otherwise known as Sean Connery!), more than 64 kilometres away in the easternmost part of the Argolid.

From there they could reach the coast and cross to the Island of Spetsas – and hopefully on to Crete.

The drive today takes just over an hour, taking you up into the hills lying inland of the coast. The journey took Bernard a lot longer as he had to avoid the roads. Crossing the hills – often guided by escaping Greek soldiers – Bernard had to cope with the pain of injuries to his knees following a head-on collision he had suffered outside Thebes earlier in the campaign.

As he trudged along nursing his wounds, Bernard was following in the footsteps of other sick and injured travellers. For two thousand years and beyond before him, people from across the Ancient world would come to the healing centre of the Asklepieion nearby, nestling in the shadow of the great amphitheatre of Epidavrou.

Emerging from the hills to the coastal plain overlooking the sea, Bernard and Henry would be helped – as Fred had been – by the trusty Greek shepherd. Bernard recounted that here “… we met an old shepherd driving his flock back for the night. We were dead beat after our 14-hour climb over the hills, and he offered to shelter us in his hut. His wife and daughter and a Greek soldier were there, and we shared their supper – milk, warm from the sheep, rye bread, cheese and fiery wine.”

Nearing Krinidion, Bernard and Henry were warned by locals of the dangers of the village – it was now controlled by the Germans!

But they still needed to get through village to get to Spetsas. The brave locals devised a daring solution that would see Bernard and Henry driven straight through Krinidion – in what Bernard described as “a ramshackle old car” – huddled in the rear, their army caps removed. In an escape worthy of James Bond, they were waved through the German checkpoints unnoticed as their local driver grinned and waved his security pass – a pass approved by the Germans themselves!

Further south, at another village opposite Spetsas, Bernard and Henry were transported by more locals across the sea to the island where they joined up with 60 other Allied troops evading capture.

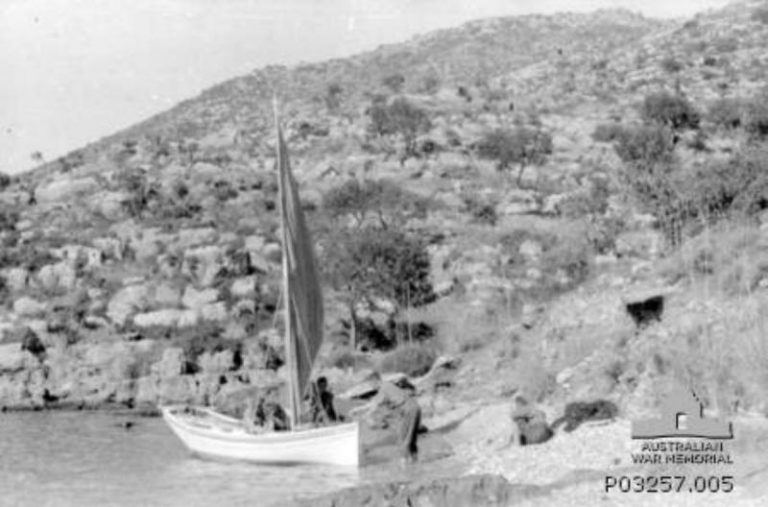

Four days later – on 6 May – Bernard and Henry and their new group sailed from Spetsas in an old ship. Commanded by “an old Greek skipper named George” and guided by a school atlas, the ship engine needed constant repair by the two Anzac engineers aboard – one Australian and the other a New Zealander. After a stop at Milos, Bernard and his group made landfall on Crete on 10 May to a warm local welcome: “A crowd welcomed us on the wharf and we had a feast of bully beef and biscuits, and settled down for a rest in camps.”

Unlike the 6,000 other Australian troops who were now prisoners or war, Bernard had escaped captivity. He would return to convalesce in Cairo. Bernard was awarded the Order of the British Empire. Not bad for a young St Ignatius boy from Richmond.

Bernard survived the war and was discharged in 1946 – returning to Richmond, a suburb that would welcome thousands of new post-war migrants from the land that he had fought to defend.

The story of the escapees of Corinth and the Argolid was repeated across the length and breadth of Greece, from Macedonia to Crete. Bernard and Henry, Fred and George are just four of the hundreds of Australians and other Allied soldiers who made their escape from captivity with the help of the local Greek population. Their journeys and their helpers should be remembered and honoured both here and in Greece.

* Jim Claven is a freelance writer and trained historian with a Masters degrees from Melbourne’s Monash University. He has researched the Anzac trail in Greece across both World Wars, and especially the Hellenic connection to Anzac through the role of Lemnos in the Gallipoli campaign. He has been secretary of the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee since its creation and is a member of the Battle of Crete and the Greek Campaign Commemorative Council. Jim thanks Jenny Krasopoulaki and the Pankorinthian Association of Melbourne and Victoria for encouraging his research. This is part three of four of his articles on the Anzacs at Corinth and the Argolid. He can be contacted at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au