A personal pilgrimage to the home of the island’s unique connection to Australia’s Anzac story led me to Lefkada in late May 2016. Lefkada and the nearby island of Ithaca share a connection to Homer’s great tale of the warrior Odysseus and his voyage to and from war. In the early 20th century some archaeologists argued that Odysseus’ ancient Ithaka was in fact modern-day Lefkada. Various sites on the island were placed in Homer’s story. I will leave that argument to the experts but Lefkada has another story of emigration and return connected to war.

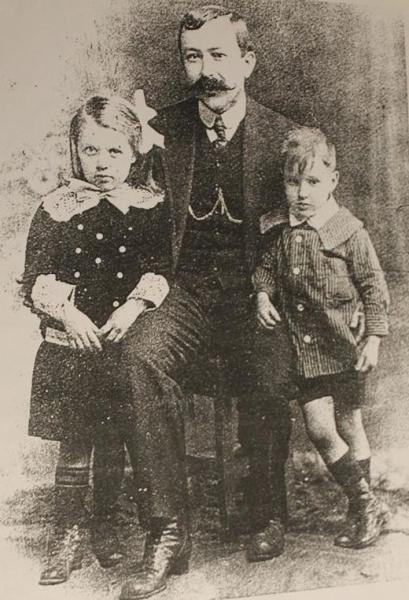

Lefkada, Ithaca, and Kastellorizo share the honour of being the sources of some of Australia’s first Hellenic migrants. From the late 19th century and into the early 20th century, many Greek villagers made their way to distant Australia to make their fortune. One of these was Gerasimos Zampelis from the village of Marantochori in the south of Lefkada.

The road to the village winds along the western coast of the island, dotted with seaside resorts and hotels. But as I turn north to the centre of the island, I see a different Lefkada – one of trees, farms, vineyards, and lush gardens.

The village sits nestled in its valley with high mountains towering above.

I am told by locals that in the past the lack of water made it difficult for many villagers to make a living. A photograph taken by German archaeologist Wilhelm Dorpfeld in 1901 shows a hardy village home – but the struggle to escape poverty is obvious. It is from this Marantachori that Gerasimos and his brother left at the turn of the century.

Today the village is green and abundant. The homegrown wine of the village has won many awards. And the variety of local honey, olives, and herbs on offer at the roadside booths is testimony to the abundance and quality of local produce. I am a guest of Gerasimos’ relatives and they maintain a magnificent cottage garden of which any Greek Australian would be proud – tomatoes, potatoes, lettuce, herbs, all sorts of fruits, plus chickens and sheep – as well as olive trees and grapevines. The hard-working Katy Zampelis is justifiably proud of her garden.

Lefkada – like all of Greece – has been affected by the financial crisis. But the local abundance and the improving tourism provide an optimism for life in the village. Katy’s partner Costas says that no matter what they will survive. “You can’t put two feet in one shoe,” he tells me.

Back in the 1940s the situation was very different. The withdrawal of the Italians brought the Germans to Lefkada. Now, just as in Crete and elsewhere in Greece, many villages contain moving memorials to the deadly reprisals carried out by the Germans on the people of Lefkada.

Katy’s mother Panorea Zampelis was 94 when I met her. She told me of how twelve local villagers were murdered by the Germans in retaliation for the resistance of the local people to the occupiers. She tells of other villages who suffered a similar fate. As I travel across the island – from Lefkada town itself to that in Marantochori’s neighbouring village of Kontorena – marble memorials stand testimony to the resistance of the Greek civilians.

Dressed in her traditional Lefkadian dress, Panorea poses with her gun as she tells me of the time the Germans came to Mandarochori. Her resistance is palpable and one that any Cretan or Maniot would be proud of.

Lefkada is indeed a beautiful island – as are many of the Ionian islands that came be seen from its coasts and mountains. Not far from Mandarochori the famous beaches of southern and eastern Lefkada dot the coast. Many of these are tiny inlets, like Afteli and Ammoussa. Costas tells me of how a famed resistance fighter would attack the Germans from the sea, only to withdraw to caves along Lefkada’s coast out of reach of the enemy. Sitting on one of these beautiful beaches with their turquoise water one can imagine the andartes finding safety in the myriad of inlets, many almost inaccessible by land.

As I drive along the west coast there is much evidence of the recent earthquake suffered by the island. The roads are strewn with rocks and cracked in many places, making the drive slow and arduous. One of the most tragic images I have is that of the church and cemetery in the little village of Athani.

The power of the earthquake is shown in the collapsed church building and broken gravestones. Yet somehow the church tower remains erect while the church beneath has been reduced to rubble.

When the Ionian islands – and especially Cephalonia – suffered a worse earthquake in the early 50s the devastation was catastrophic. And during this time of need, some of Greece’s erstwhile Allied defenders came to her aid. Patrick Leigh Fermor, philhellene and former SOE agent who had fought in Greece in the Second World War, came to the Ionian islands to promote British aid for the locals.

As I travel further up the coast – to the beautiful beaches of Kalamitsi and Kathisma – and enjoy a bathe in the Ionian Sea, I imagine what the Australian sailors who came to this sea in the First World War thought of the islands they passed. It is not well-known that six Australian warships defended the Ionian and Adriatic Seas, based at Corfu and Bari in Italy. They sailed the region for three years, calling in to ports and no doubt interacting with the locals. I wonder if they ever made a call at Lefkada.

It is fitting that my thoughts end with the sea. As Odysseus sailed these waters, so did the Anzacs and so did Gerasimos as he made his way to distant Australia. But unlike the wily Odysseus he was never to return.

But his son – young James, born in the Melbourne seaside suburb of St Kilda – would come to Greece, perhaps as a sort of proxy for his father.

He would fight alongside fellow Anzacs and other Allied troops to defend his father’s homeland from the invader. From Servia in the north all the way to Crete, Private Zampelis’ service would make both Australia and Greece proud. Sadly he would be killed in Crete in May 1941 and his body never found after the war. He has the distinction of being the only Hellenic Anzac to have served and been killed in the Greek campaign of 1941.

James’ fight stands as a fitting comparison to the brave Panoera, for whom the memory of the war and the responsibility to defend her homeland is never far from her mind.

Moves are afoot to memorialise James’ service in Melbourne and at Mournes in Crete where he was killed. Maybe there should also be a memorial to James in this little village of Marantochori to commemorate the sad homecoming of this son of one of its villagers who died defending Australia, Greece, and freedom 76 years ago.

The Lefkadian Cultural Association is holding a commemorative event in honour of the Lefkadian Anzacs who served in WW1 and WW2, including Private James Zampelis, at Moonlight Receptions, 622 Nicholson St, North Fitzroy, VIC on Sunday 22 October starting at 2.00 pm. For more information contact clairegazis48@gmail.com

*Jim Claven is a historian, freelance writer and member of Melbourne’s Battle of Crete and Greece Commemorative Council. He has researched the story of the Hellenic link to Anzac over many years, including the story of Private James Zampelis. He acknowledges the support and hospitality of the Zampelis family both in Melbourne and on Lefkas, without which this story could not have been written.