There’s an old journalist motto: “If the truth gets in the way of a great story, well, so much for the truth.” Okay, this is not something taught in any media school, but it is a joke often heard in bars where journalists hang out, sharing stories.

As far as great stories go, how about the absolute greatest guitar legend in rock history, Jimi Hendrix, paying respects to one of the absolute masters of bouzouki Manolis Chiotis? The tale is well-known, and it has been circulating for years, from obsolete magazines to TV shows looking to fill airtime, to the clickbaity websites of our times. According to the apocryphal tale, when asked by a journalist how it felt to be the greatest guitarist ever, the man who dissected The Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock answered: “You believe I’m the best because you have not listened to Greek Manolis Chiotis playing his bouzouki.” When did that happen? When did this interview take place? Who was the reporter? Where was it printed – or broadcast, for that matter? Nobody knows. There is no evidence, no source of origin, nothing to give this story any credit. And yet, Mary Linda herself, the legendary singer, wife and artistic alter-ego of Manolis Chiotis went on to perpetuate the myth, by stating in a TV interview that the famous rock god was a frequent punter in the pair’s regular residencies in New York’s 8th Avenue Greek nightclubs, admiring Chiotis technique and going into lengthy discussions with the bouzouki player. Old age is known to do terrible things to memory, which is not the best storytelling tool, either way, as Mary Linda knows too well, being a seasoned entertainer. It doesn’t matter if she grew to believe that story, or if she deliberately chose to confirm it, despite no other source existing; the likelihood of Hendrix being mesmerised by Greek bouzoukia in 1965 (as the TV show in question, Mihani tou hronou – Time Machine claimed) is next to none.

In fact, one of the most acclaimed music journalists in Greece, Phontas Troussas, has tried to debunk this myth in his blog, Diskoryxeion (Vinylmine), presenting two sources of reference: the dates of Jimi Hendrix’s live recordings (detailed in a collector’s site at angelfire.com/indie/jypsyeye/Hendrix_CollectorsList.pdf), which doubles as a rather accurate timeline of his performances and, on the other hand, the dates when Chiotis travelled to the US – this was an era when transatlantic journeys were a big deal, after all.

CHIOTIS IN NEW YORK, NO JIMI IN SIGHT

According to a story printed in the leading daily Greek newspaper Ta Nea, Chiotis visited the States three times: in 1956, in 1959 (when Hendrix was still in high school, that is) and last, but not least in 1964, which is the most significant, since this visit lasted four years until 1968. What was Jimi Hendrix doing during these years? He was playing with artists such as Little Richard, BB King, and the Isley Brothers, before being ‘discovered’ by Chass Chandler, the Animals’ bassist, who became his manager and urged him to move to the UK in 1966.

His claim to fame in the US is his now-legendary appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 (his only visit to the US, that year). So, as Troussas presumes, the only possibility of Chiotis and Hendrix meeting would not be in 1965, when Hendrix was practically unknown, nor in 1966, when he was in the UK, or even 1967, given that Monterey is in California and Hiotis was in New York.

This leaves no other option than 1968, the last year of Chiotis’ New York residency. The Hendrix performance timeline allows researchers to entertain the possibility of this happening in March or April 1968. Unless, this happened before Hendrix became famous, before his trip to UK, sometime between 1964 and 1966. If this is the case, kudos to Mary Linda who remembered the name of this unknown session musician marvelling at Chiotis’ technique.

There is nothing to suggest that this story is true. Chiotis and Linda were photographed with Grace Kelly, Prince Rainier of Monaco, Maria Callas, and Aristotle Onassis and their appearance in the White House, where President Johnson granted them an indefinite ‘green card’, has not been disputed. Other things don’t add up. Leaving aside the fact that bouzouki and guitar are two very different instruments, the two musicians have no similarities in technique or esthetic approach to music; anything to signify that Hendrix might have the slightest interest in Chiotis and his music. Furthermore, the ‘greatest guitarist’ hoax is a long-standing one, and not always with a reference to Greek artists. The most prevailing urban legend has Hendrix appearing on The Tonight Show and answering the question by a nod to either Eric Clapton, Rory Gallagher, or obscure christian-rock virtuoso Phil Keaggy, whichever source one opts to believe. This story is also false. Hendrix appeared only once on the show, and the audio clip of this appearance (the video has not survived), has no evidence of such discussion. He did appear in another popular talk show of the era, The Dick Cavett Show, where he offered praise to an up-and-coming guitarist, Billy Gibbons (later to be associated with ZZ Top), though he did not call him the greatest guitarist – nor did he ever say that the greatest guitarist was a sleek suit-cladded bouzouki player from Greece.

JAZZMEN IN GREECE

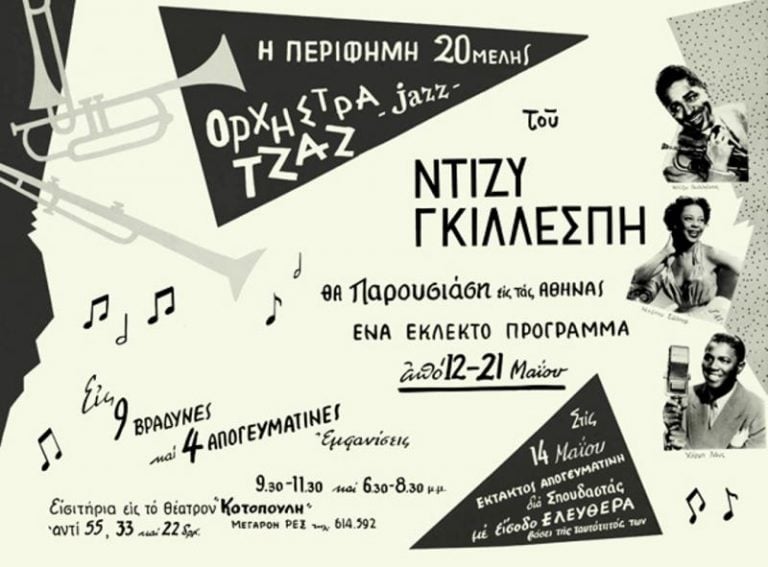

This is not to say that international stars were ignorant of Greek music. The 60s was the era when Greece blossomed as an international tourist destination, as well as a filming location. It was also an era when the US State Department started an ‘ambassadorship’ programme for jazz musicians who travelled around the world. Both Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie played in Athens, the latter being famously photographed with the traditional attire of the Evzones in the Acropolis for his album Dizzy in Greece, which was not a live recording. This visit, which occurred in 1956, offered another opportunity for myth-weaving, this time by one of the most significant Greek composers, Mimis Plessas, who had studied and performed in the US. In an interview for the Jazz & Τζαζ magazine, he stated how Dizzy asked him to suggest a Greek song for the concert. The composer made a jazz arrangement to a traditional song A Boat from Chios, instructing the legendary trumpeter (who was perplexed by the irregular rhythm) to do what another trumpet player had done before, pointing to Ziggy Elman and his famous solo in Benny Goodman’s great hit And the Angels Sing. Plessas says that it was Goodman’s drummer, the Greek American legend Gene Krupa, who turned the ballad (sung by Martha Tilton) to a kalamatiano, but the truth is that Ellman was just referencing the klezmer music of his Jewish ancestry (other nations, from the Balkans up to Russia, also claim the few exotic-sounding bars). Plessas then says how Dizzy taught him and Quincy Jones the basics of film scoring, helping them make their first steps in what resulted in a long, prolific and lucrative career.

So yes, musicians tend to embellish things, and Benny Goodman did not play a kalamatiano song, or any other kind of traditional Greek music (in fact, in this recording, sitting in the drummer stool was not Gene Krupa, but Lionel Hampton). He did, however meet a Greek music legend, in New York, at the same place and time when the alleged Hendrix and Hiotis encounter took place: a Greek nightclub on 8th Avenue, in 1965. The club was called Ali Baba and it featured clarinettist Tasos Halkias, one of the famous Epirot clan of musicians, and a true master of traditional clarinet.

“One day, the boss lady came and told me that a dozen people came in the club, Benny Goodman among them,” he narrates in his biography Remembrances and Notes of Tasos Halkias (written by Andreas Chronopoulos). “They were interested in a tune which was supposed to be written in the form of Greek traditional lament (miroloi) and they did not know how. It was for a movie of Richard Sarafian, and a scene features a mother losing their daughter, so they needed a lament and somebody told them of the Ali Baba club where a man named Tasos Halkias plays, who could help.” The movie in question is Richard Sarafian’s Andy, a drama about a man of Greek origin with intellectual disabilities, and the challenges his family faces. The film’s composer, Robert Prince, was known in jazz circles and had arranged some Benny Goodman tunes (not least among them the Meet the Band number, in which he introduced his players), which gives some credit to the story. But again, it’s the storytelling itself that makes it charming: “When the boss lady told me that we have Benny Goodman in the house, knowing who he was, I became too nervous and could not play what they wanted. She was acting as an interpreter – because I couldn’t speak English and Goodman said: ‘I want him to play a miroloi. What is this thing?’.” The clarinettist, nervous, first headed to the bar, downed a couple of whiskeys and then went on stage. After he played, the ‘king of swing’ was impressed by his ‘Byzantine’ glissandi and the fact that Halkias did not read music. “He loved it, he was crazy about it. He got up on stage, kissed me and gave me a mouthpiece with his name on it, and a few reeds.”

GREEK MUSIC LOOKING FOR VALIDATION

Strangely enough, another acclaimed traditional clarinettist, also named Halkias, though not related, also claims meeting Goodman and Armstrong in New York. There is an ongoing animosity between Petro-Loukas Halkias and the members of the Halkias clan, because the former has implied being related to them, when in fact he is not – they claim that he also stole that story. But he has another interesting story of his own, which he never fails to deliver, when he is featured in a TV show. That, while in New York, he became a member of the Musicians’ Union and attended a few of the meetings, where dozens of musicians of different origin were present. Asked to play a tune from Greece, he played a pogonisio and one of the members went up and asked to buy part of the melody, paying him $1000 for it. His name was Richard Finch and he used the few bars he ‘bought’ as a basis for the 1975 international disco hit That’s the Way I Like It by KC and the Sunshine Band. Is this true? Waiving his rights for the cheque, Petro-Loukas Halkias lost his chance of appearing as one of the songwriters. But his story is certainly a crowd-pleaser.

Why are these stories always coming up, despite at least some of them being so obviously false?

Because Greek artists – but mostly Greek media – are always looking for some kind of international validation of their merit. Do they need it?

Petro-Loukas Halkias is an extraordinary virtuoso, whose career is by now noncontestable (his willingness to work with musicians from Africa and India has also resulted to some magnificent works of art); Mimis Plessas is the composer of one of the most iconic Greek music albums ever recorded, O Dromos, and the creator of a large number of classic hits – being the only musician in Greece to be equally fluent in folk music, bouzoukia, soundtracks, and jazz. As for Tasos Halkias and Manolis Hiotis, these gigantic pillars of Greek culture, neither of them ever needed this kind of external ‘international’ validation. Their music is an integral part of the whole of Greek culture. Tasos Halkias is the eternal beacon of Epirotic music, a true master of the Greek clarinet and an artist whose teachings on the importance of tradition – and advice as to how best preserve it, remain as true and relevant today as ever. As for Hiotis, he was a true genius of the bouzouki, the man who single-handedly changed the course of the instrument, the way it is fabricated, people’s perception of it, the history of Greek folk music as a whole. It was Chiotis who added a fourth (double) string to the instruments three strings, changing its tuning and allowing it to play the ‘Western’ scales, along with the ‘Eastern’ ones. This helped him infuse folk music with Latin and swing elements, creating his signature sound. He was also instrumental in the creation of the bouzoukia culture, taking folk music out of the neighbourhood tavernas and dives it was heard and building a ‘Greek nightclub’ concept around it. The rest, as they say is history (but nobody seems to claim ownership for it).