The story of Orpheus’ descent into the underworld to retrieve his beloved Eurydice has fascinated people for centuries.

Plato wasn’t a fan. He thought Orpheus took the easy way out. He reasoned if Orpheus really wanted to be with Eurydice, he should have just killed himself and joined her in death forever. Descending into the underworld, so he could recover his wife and still enjoy an earthly existence, showed only half-hearted devotion. He saw it as a case of Orpheus wanting to have his cake and eat it too.

It was the Roman poet Ovid who made this tale into the romantic story we know today. In his version, the god of love refuses to let Orpheus reconcile himself to the death of his wife and inspires him to make the journey to the underworld. Orpheus charms the rulers of the underworld and their attendant Furies with his passionate song. They weep tears for his loss, and allow him to take Eurydice back into the sunlight.

The only proviso was the famous interdiction: Orpheus must never look back as he undertakes the treacherous climb to the mortal realm. Despite this warning, overcome by his passion and fearful he might lose his beloved, Orpheus makes the fatal mistake of turning to look at his wife. In doing so he loses her for eternity.

On many levels, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice doesn’t make sense. Why throw away at the last minute everything you’ve struggled so hard to get? The composer Offenbach memorably thought the story fundamentally absurd and lampooned it in his comic opera Orpheus in the Underworld, an opera best known these days for giving us the music of the can-can.

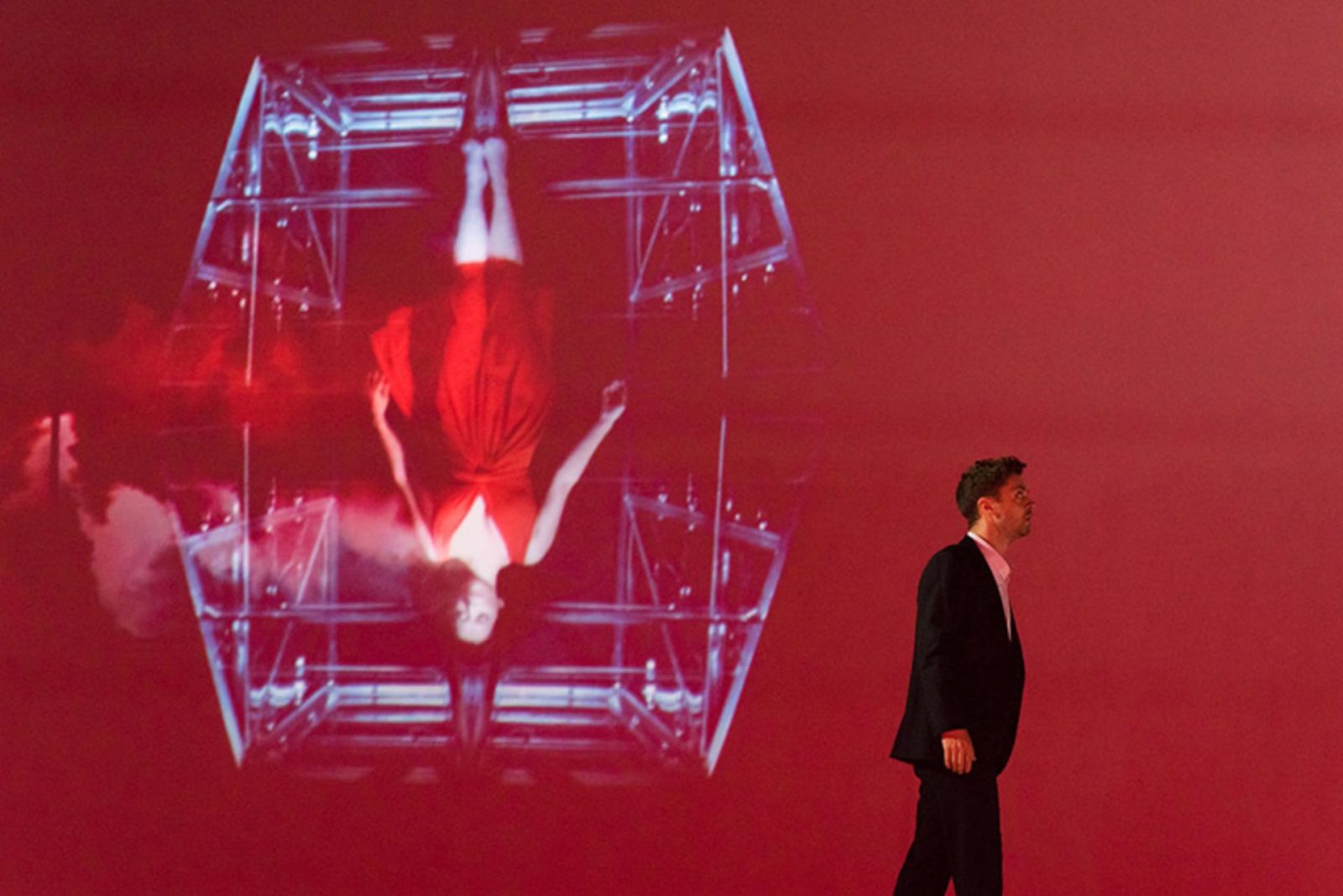

Orpheas us not supposed to look back at his true love. Photos: Jade Ferguson, QPAC

Offenbach’s is just one of dozens of operas based on the Greek myth. But the most enduring is by 18th century composer Christoph Willibald Gluck.

An exploration of tragedy

Underpinned by Ovid’s version of the story, Gluck’s opera is on now in Brisbane in a radical reinvention by Opera Queensland and Circa. It is raw, physical, and confronting.

Gluck is famous for adding a happy ending to Ovid’s tale. In his opera, the goddess of Love is so moved by Orpheus’ despair at his double loss she violates the laws of Hell and reunites him with Eurydice at the end.

This production resists such moments of unadulterated joy. This version is interested in exploring the tragedy implicit in this story. Is this myth about the power of love or the triumph of death? This production argues it is both.

The opera may be called Orpheus and Eurydice, but this opera is no two-hander. The dramatic centre of the opera is the figure of Orpheus, played with intense vulnerability, passion and desperation by British countertenor, Owen Willetts.

This concentrated focus on the figure of Orpheus is reinforced in this production by the decision to set the opera in a stark, bare asylum. At times, there is nothing on stage but white walls and Orpheus’ anguish.

READ MORE: Nikolas Karagiaouris on the past, present and future of opera in Greece

Orpheus’ descent into Hell is envisaged as a descent into madness. Staging the opera as a form of psychodrama permits a clever casting move in allowing Circa artistic director Yaron Lifschitz to combine the roles of Love and Eurydice. This creates a much more substantial female role that serves to balance Orpheus. The twin roles are sung by a highly assured Natalie Christie Peluso.

Orpheus and Eurydice is not an opera traditionally associated with powerful physicality, so the decision to pair opera singers with circus performers is an interesting one. On the whole it is a successful partnership, but at times the novelty of the acrobatics threatens to draw attention away from the singing and the drama.

It is hard to lament for the death of Eurydice when you also want to applaud the triple somersault you’ve just caught out of the corner of your eye. The vibrant athleticism of the circus performers also has a tendency to show up the chorus. As they roll, tumble, leapfrog, and pirouette on stage, the circus troupe makes the largely static chorus look decidedly flat-footed.

Yet, as the opera progresses, the value of the collaboration begins to show itself. Watching Orpheus and Eurydice physically clamber up the bodies of the acrobats and stumble as they take each precarious step – balancing on shoulders, heads and outstretched arms – powerfully evokes the physical demands of descending into the underworld.

The final act in which chorus, principals and circus performers combine to stage the twin triumph of love and death, is a remarkable piece of performance. Completely captivating and deeply moving.

Lifschitz and his production team should be applauded for attempting to take this story seriously. In situating this opera between the opposing poles of love and death, they have produced a cerebral drama that invites us to reflect on what it means to be mortal.

Orpheus and Eurydice plays at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre, South Bank, Brisbane, through to 9 November.

* This article first appeared in The Conversation. Alastair Blanshard is the Paul Eliadis Chair of Classics and Ancient History Deputy Head of School at The University of Queensland.