Dora Houpis moved in with her parents on 25 March to be with them when the Covid-19 restrictions enforcing home isolation and social distancing came into effect.

The previous week on 20 March, marked the 49th anniversary of her family’s arrival in Australia on board the Patris, the second-last ship to bring Greek migrants to Australia.

She has used this time as an opportunity to find out more about her parents’ lives and, in particular, her father Spiros:

There is an 87-year-old Greek man in Melbourne who, at the age of 36, migrated to Australia from Greece, with his wife and three children,on the Patris, in 1971.

Hundreds of thousands of Greeks had made the same voyage before him.

That man is my father, Spiros Houpis. He wants to tell the young Greek generation, about his generation of migrants who faced extreme hardships in their country and who came to Australia because of this country’s mammoth white-Australia immigration program.

He wants to tell the young about war, disasters, resilience and perspective in the face of the Coronavirus pandemic.

He wants to dedicate his story to all the Greeks who have migrated to Australia, particularly between 1945 and 1975. He wants to do this because he says many οf them experienced, metaphorically-speaking, “The Passion of the Christ” (Τα πάθη του Χριστού”.

At dawn, on 17 October 1941, the Nazis invaded the adjoining villages of Lower and Upper Krousouves, in the Greek province of Macedonia – they burnt them, killed all the men aged 16 to 65 years old, and left the elderly and widows to bury their dead. This was in retaliation for the two villages habouring resistance fighters.

This day was the end of my father’s world, but it was not the end of the world.

With his father and adult brother dead, he was now the head of the family. He was seven years old.

My father and his 13- and 19-year-old sisters walked 25km to his mother’s mountain village of Vrasna. His mother rode on a donkey.

“Then we had war with weapons,” he said. “There were the Germans, Bulgarians and Italians.

“Now, with the Coronavirus, we have a war without weapons. It’s a big difference.

“You can’t leave to go outside, but at least you have food to eat. You just don’t have the freedom.”

READ MORE: When coronavirus arrives in your isolated Greek town

“Yes, my mother sent me out to the village to beg twice in 1941,” my father said. “She sent me, not my sisters, because I was young and wasn’t ashamed.”

He said he was given five to six pieces of bread for his begging efforts.

“There was nothing else. Even if you wanted to, there was nothing else.”

Then the spring came five months later in 1942. The wheat was harvested and his mother made bread. The olive trees bore crop and they marinated olives.

“We didn’t have oil, but at least we had bread and olives.”

The Second World War ended and the Greek civil war began.

“Brother fought brother” in that war. Then, three years later, in 1949, it too ended, the communists were defeated and Greece began rebuilding.

Greek government officials asked the surviving villagers of the decimated Upper and Lower Krousouves to come down from the mountain, unite and rebuild one amalgamated village on the Thessaloniki-Kavala Highway. The village elders agreed.

So, the government built them a new village on the important trade and carriage route and gave it a new name, Nea (New) Kerdillia, named after the nearby Kerdillion mountain range.

There was then peace and some prosperity. He learnt a trade. He married off his sisters, Stavroula and Chrisanthi, and gave them dowries.

READ MORE: 10 things to do: Keep calm and think Greek

Then he married a girl named Panagiota, from the same village and had three children. He named all his children after people who had died. Angeliki (Angela), after his mother who was buried on the day he went to ask for his prospective wife’s hand in marriage (“λόγο”), Thomas after his brother who was murdered by the Nazis, and Theodora after his seven-year-old brother-in-law who died of a burst appendix, in 1944.

He established a building business to feed his family and served as mayor.

Then the military junta took over on 21 April, 1967. By 1971, he decided to leave for Australia.

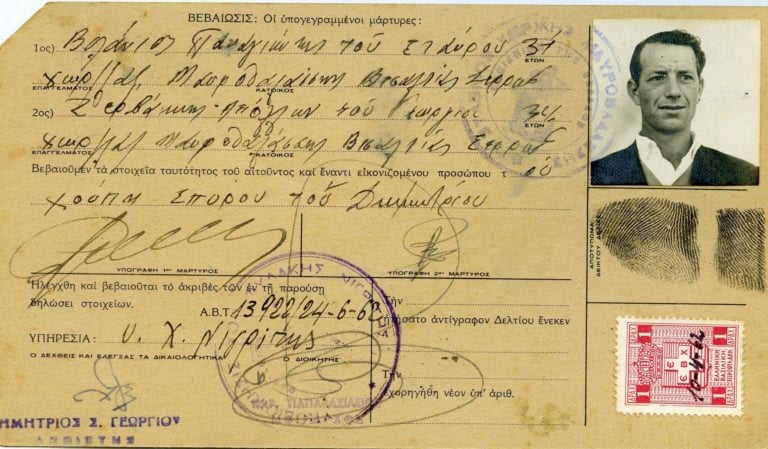

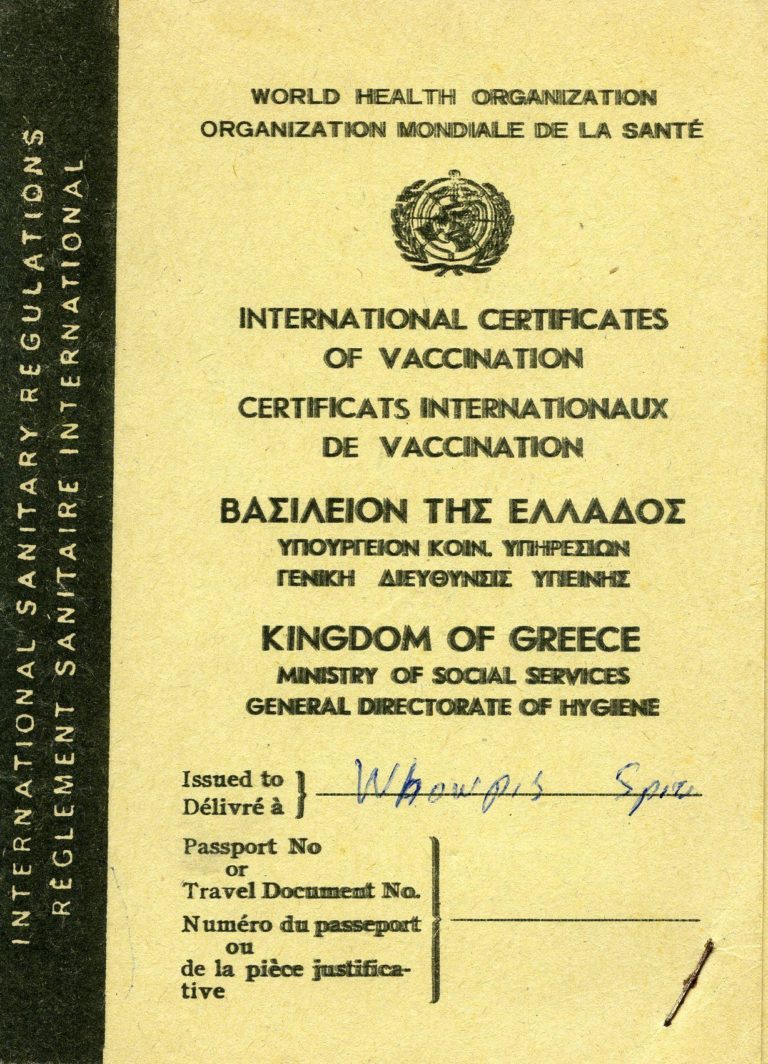

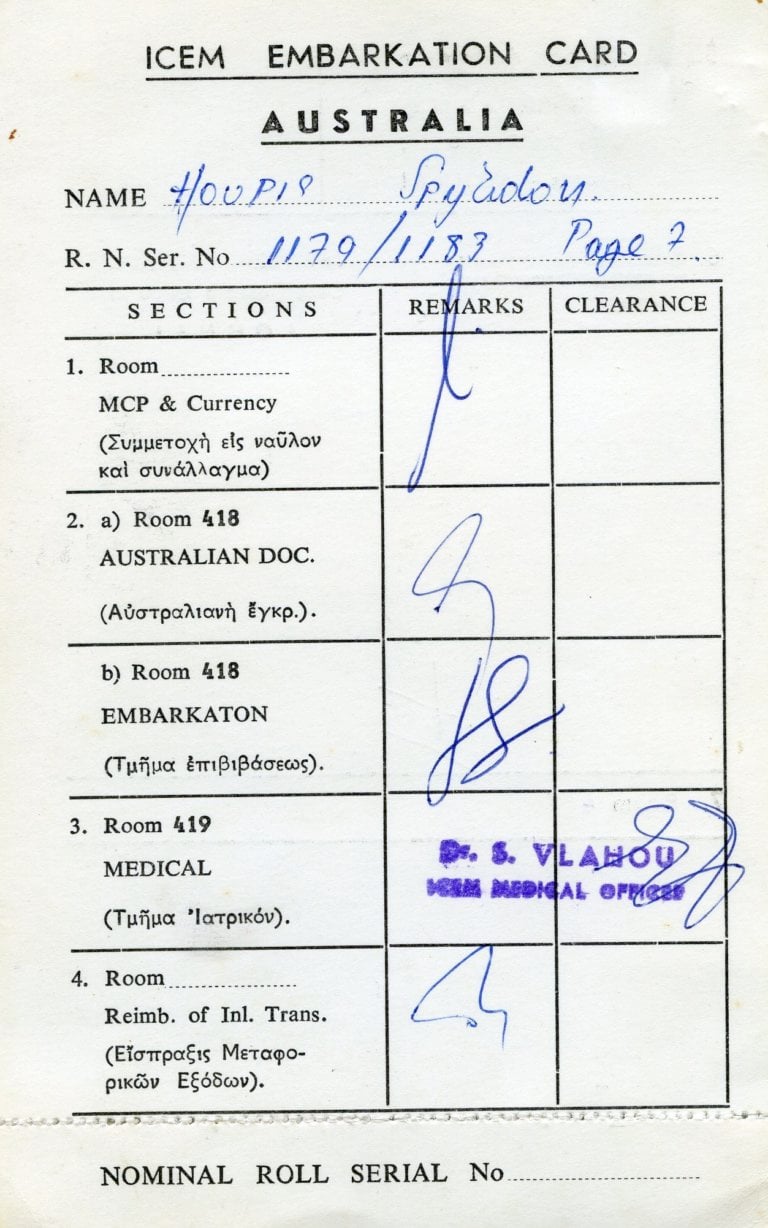

The Suez Canal was closed, so he landed in Melbourne, Australia, on 20 March 1971,( see scanned boat boarding pass) after nearly a month travelling by plane and sea.

He was now displaced for a second time. He was 36-years old and again the head of his family, this time of a wife and three children.

There was peace in Australia, but life was hard. He spoke no English and his builder qualifications weren’t recognised. He worked in factories instead.

He bought a house, educated and married off his children. He became a grandfather.

He fell sick and was sacked from the metals factory where he had worked. He recovered his health and qualified for an age pension at 65 years old.

Now, 22 years later, the Coronavirus, has come along and has locked him and his wife in their home.

“It’s a bora* (a strong, cold wind from the north),” he said. “It will pass.

“At least you can go to the shops.”