He was known simply as “O Tom” by the mountain villagers who were his brothers-in-arms, and his name is still revered in Crete today, particularly in his beloved Amari Valley.

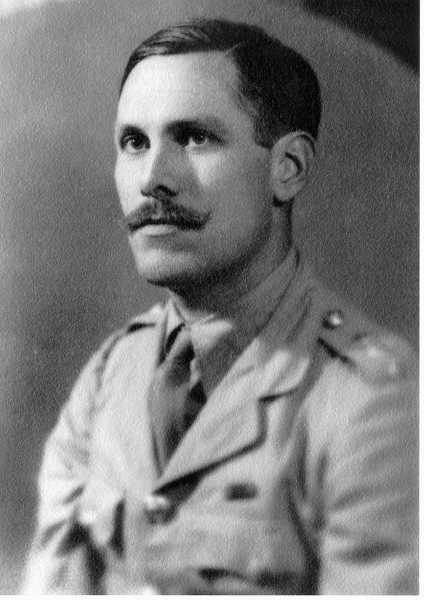

With his near perfect command of Greek, his handlebar moustache, and shepherds’ clothing, Tom blended almost seamlessly into the mountain culture, his British gait betraying him to sharp-eyed locals, but not to the occupying Germans

Tom James Dunbabin’s story is one of an extraordinary individual and a remarkable bond. A modest, unassuming man, Dunbabin became central to the Allies’ relationship with the Cretan resistance between 1942 and 1944, but his roots were half a world away.

He was born in Hobart in 1911, moving with his family to Melbourne as a child, and later to Sydney. From a young age he demonstrated academic brilliance, achieving outstanding grades throughout his schooling. In 1928 Tom won the prize for the highest general proficiency in his final year at Sydney Grammar School and enrolled at Sydney University a year later. When his family relocated to London, he moved to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He graduated with a Literae Humaniores Degree (Classics) in 1933, and set out on a career as an ancient historian and archaeologist.

For two years at the British School of Archaeology in Rome, he studied the Greek colonisation of Italy for his PhD thesis. He then relocated to the British School of Archaeology in Athens, taking part in excavations at Knossos, Crete from 1936 to 1939. While at Knossos, Tom became engaged to fellow archaeologist Doreen de Labillere on the terrace of the Villa Ariadne, the headquarters of the British School. They married in 1937 and had two children; John in 1938 and Katherine in 1941. Elected a fellow of All Souls College, his academic career was interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1939.

Tom enlisted in the British Army, trained as a commando, and was transferred to the Intelligence Section in July 1940. The following year he was recruited into the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and sailed to Egypt. Posted to Force 133, he landed on Crete in April 1942 and, except for brief periods spent in Cairo, lived with the shepherds in the mountains of Crete for the following three years.

With his near-perfect command of Greek, his handlebar moustache and shepherds’ clothing, Tom blended almost seamlessly into the mountain culture, his British gait betraying him to sharp-eyed locals, but not to the occupying Germans.

During his time in Crete he was based in the Rethymno and Heraklion prefectures, but mostly in the Amari Valley, living in caves on the slopes of Mount Ida and the Kedros Mountains. He depended entirely on local shepherds for his safety, and on villagers for food and clothing.

Throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, SOE organised local resistance groups and supplied them with arms and equipment to carry out sabotage operations. In Crete, the severe retaliatory reprisals meted out to civilians caught assisting the resistance made effective operations hugely difficult. Suspects were tortured and their villages burnt to the ground. Dozens of villages were destroyed and over 2,000 civilians killed because, in Tom’s words, “they were sturdy chaps who looked as though they might belong to resistance groups”.

Tom’s role, as SOE leader on Crete, became one of collecting information about German dispositions and troop movements, and transmitting this information to the Allied Middle East HQ in Egypt. Information and documents were gathered by brave Cretan collaborators working in Heraklion and Chania, often as assistants to the Germans, who passed them to runners, who took them to Tom and his radio operators in the mountains. Propaganda campaigns targeting the occupying force undermined their loyalty and resulted in many defections, including the Italian General Angelo Carta.

Tom became well known for his strong leadership in SOE, his steadfast dealings with Cretan resistance leaders, and his understanding of the Cretan people. As the war in Europe turned in favour of the Allies, resistance leaders, believing an allied invasion of Crete was imminent, were determined to take action against the German occupiers. Tom, aware of the Allied invasion of Sicily, knew an Allied attempt to retake Crete was unlikely. His diplomacy skills were severely tested in preventing the lightly-armed resistance groups attacking the dispirited, but well-armed Germans, actions that could only lead to disaster for the Cretan fighters and the local population.

In October 1944, the Germans withdrew from most of the island, forming a defensive ring around Chania. Tom, the senior British officer on Crete, worked with local officials and resistance fighters to successfully implement civilian rule, without the bloody battles between left and right that engulfed mainland Greece. His wise counsel, tireless work schedule and engaging approach became legendary. Many times he pleaded with military officials in Egypt for humanitarian supplies to prevent Cretan starvation. Winter food stores had been plundered by the retreating Germans, who destroyed what they couldn’t take.

In early 1945, Tom left Crete and was appointed as Monuments, Fine Arts and Antiquities Officer in Athens, with the task of cataloguing the war damage and pilfering of treasurers from Greek museums and archaeological sites. Before taking up the appointment, he was given a month’s leave in Britain, spending it with Doreen and the children. While there he resolved that following his Athens appointment, he would return to his family and academic career in Oxford.

At war’s end Tom retired his military service and took up his fellowship at Oxford University as Reader in Classical Archaeology. He continued his work in Greece and other Mediterranean countries, spending time in Athens at the British School. From there he maintained his connections with Crete, visiting the island and always regretting that he never had enough time to see all his friends.

In 1948 he published his monograph, The Western Greeks, on the Greek colonisation of Italy from the eighth to the early fifth century BC. His view that these settlements were for trade, rather than conquest and expansion of empire, was accepted with reluctance by his peers, but has since been supported by excavations and studies. Tom’s last book, The Greeks and their Eastern Neighbours, explored Hellenic contacts with the eastern Mediterranean in the eighth and seventh centuries BC.

In early 1955, Tom returned from his last trip to Athens suffering from back pain. His condition deteriorated and he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, a disease that today remains almost always fatal. On 31 March he died at the age of 44.

His family was devastated and his passing was felt around the world. Doreen and the children had lost their husband and father, and his Tasmanian relatives one of their “favourite sons”. On Crete there was huge sadness at the loss of one of their own. The honouree citizen of Athens and Heraklion was praised for his work as resistance fighter, masterful politician and humanitarian. A reluctant hero, Tom would have been uncomfortable with the thought of being honoured in death.

My uncle began to write an account of his time in Crete in the early 1950s but was unable to complete it before his death. In 2010 I received a copy of his first handwritten draft, and realising its significance, I transcribed it.

In 2015 the transcription, along with Tom’s biography, was published in Heraklion, in Greek and English, by the Society of Cretan Historical Studies.

Copies are available from the Historical Museum of Crete at www.historical-museum.gr, and through the author by emailing tom@bangor.com.au