Every day in Athens people stroll past ancient statues; statues that were sculpted in classical times. But imagine if these statues could talk and tell their stories; stories of a culture and a language that are far removed from our current world of text speak and social media posts.

Well what if I told you that somewhere in the Mediterranean, there are statues that seemingly spring to life with their stories and history?

Deep in the mountains of Calabria in Italy, ancient Greek statues exist, except they’re very much human and they are the guardians of Hellenes’ ancient past, a past that seemingly existed only in the history books.

These human statues are the link via an oral language that has survived for over 2,800 years, surviving conquerors, disasters, population decline, religious conversions and poverty to remain one of the richest spoken tongues in history.

That language is Greko, a Greek dialect and arguably the oldest remaining Greek dialect in the world. It is a connection to the ancient Greek colonists who once spread across southern Italy. The Latins called it Greater Greece – Magna Graecia, with the name Graecia being of real significance given the name Greece has only really be used since independence, while across the Adriatic, this name from Epirus was used to describe the Hellenes who dominated the entire region from Napoli and the outskirts of Apulia, to Sicily.

Greko is deemed an endangered language by the EU, and one that a group of energetic activists in Calabria are racing time to save.

Sitting in the heart of the mountain with the Aspromonte (meaning White Mountain in Greko) national park in the background, I had the chance to tour a town, or rather a village, that reflects everything about the language and culture of the Greko.

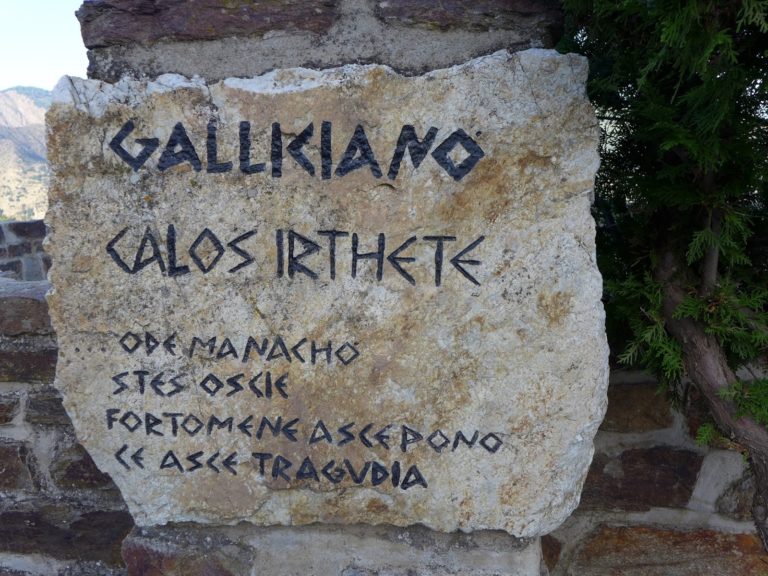

So picturesque it is almost as though it has been forgotten by time, with its authentic, traditional homes, narrow streets and pathways where fewer than 60 people remain. Modern development and apartment-style living won’t be finding their way to Galliciano any time soon. Perhaps, this is the Calabrian Greko version of the Acropolis, set at one of the highest points of the region, but rather than temples it is a gem of a village with its living, breathing statues. Galliciano for easy reference, is pronounced GaddiciAno (insert strong Calabrian accent here) and was established by Byzantine Greeks in the 700’s as Galikianon, possibly named after a prominent land-owning family.

Sydney-based lawyer and writer Costa Vertzayias visited in 1987 with his family at a time when there was a population of 200 residents. In 2002 when I last ventured there, there were around 100 people. The decline has been rapid, due in part to people seeking work opportunities in other parts of Calabria or Italy, as agriculture and quiet village living is not always enough to make ends meet.

This time around, I was lucky enough to visit with a young Condofuri Marina local, musician Pandeli Danilo Brancati as our guide, joined by London-based filmmaker Basil Genimahaliotis.

The drive up the mountain was spectacular, and just as I remembered. There is an eerie sensation unmatched by most travel destinations, almost as though the ancients look over the village. I closed my eyes and let the moment capture me, and my soul felt as though this was another Athens or the Constantinople of Calabria.

As I opened my eyes, I realised we were in need of food. This would be a problem given it was a Sunday, and the only taverna in the village was closed.

We were brought to the main square past homes where older people greeted us in a language that initially seemed foreign to my travelling companion Basil and I. Danilo however was in his element. Despite his Greko heritage, he had only learnt the language fluently three years earlier thanks to the work and vision of Maria Olimpia Squillaci, who is helping to teach the language to more people in her age group and younger in the traditional catchment of the Greko speaking region.

As we stood in the small square, a group of Calabrian and Greko speakers surrounded us. With almost no understanding of the quick witted banter, we soon enough found common ground; the poor performance of the Italian football team. That discussion seemed to elevate the already animated square, dominated by younger visitors, grandchildren of the older Greko speakers. In typical Calabrian, or should I say, Greek fashion, the conversation was loud and flowed thick and fast, until a small break in chatter. This allowed us to hear a clamour in the small snack bar nearby. Turns out some of the villagers were playing cards and backgammon at tables we soon had a seat at.

Danilo made the point that it would be ideal to actually eat. As Basil and I looked at each other in hunger and bewilderment, Danilo gave us an expression that assured us we would be fed. Mimmo Nucera, a man in his 40s who lives in the village and belongs to the Nucera family who manages the tavern, explained that in Galliciano, the taverna opens when people are hungry – even on a Sunday.

However before food, we were taken on a walk further along the mountain path where we passed a Greek flag fluttering next to an Italian. Most in Galliciano have never been to Greece, but it is clear that in their hearts, they are as Greek as can be.

As we walked, we stopped by a small church that I had visited 16 years ago. It marks an interesting change in the recent history of the Greko, who are all Catholics with the exception of a few. During the 1500s, the Catholic Church had overseen a period of confiscating Greek Orthodox churches and property, forcing them to adopt the Catholic rite. Almost overnight, the Greko had lost a key element of their Greek identity, the religion that was the hallmark of the strong Byzantine Greek era of southern Italy from the 6th century until the 11th century AD, and strengthened further by the refugees of Constantinople and the Morea of the mid-15th century. By the end of the 1700s, the last remaining Greek Orthodox monasteries had closed.

The church was opened by Patriarch Bartholemeos of Constantinople over two decades ago and marked a change for the Galliciano people as it gave them a Greek Orthodox church and another outlet to connect with their Greek past and Greece across the Adriatic. Named for Panagia, it comes at a time when other smaller churches have opened in Calabria. We even had the pleasure of meeting an ordained Greek Orthodox priest, Fr Daniele Castrizio.

When we finally sat down to eat, we found ourselves seated at the taverna that had been specifically opened for us with table service provided by the Nucera family, on a picturesque patio overlooking the village with the Aspromonte Mountain almost touching us. The food, of course, was simply divine, local and fresh, with wine to match. We were soon joined by two Dutch tourists, who revealed they had heard that there was a piece of Greece in Calabria and wanted to experience it for themselves.

For the next hour, Danilo and his friends played the accordion and tambourine, playing a song that seemed to have no end, just a beginning and a future – perhaps a symbolic reflection of Galliciano. Soon children who had been playing in the small playground nearby joined in to dance and occasionally play the tambourine. If the food, music and the village had not already captured our imagination, a young boy who welcomed us with a few words in Greko, certainly did.

The language itself is said to be spoken fluently by almost 2,000 older people, yet through the work of To domadi greko, l’Associazione Ellenofona Jalò tu Vua di Bova Marina led by the community’s young people, the language in the Aspromonte region has a future. On the other side of the country, I met one of the leaders in Bologna, Eleonora Petrulli who spent hours talking to me in three languages: Greko, English and some Italian. She is apart of a campaign called ‘An me platespise ZIO’ (If you speak me I LIVE) – a poignant title, as it requires as many of us to speak the language to stem the decline and take it forward.

In Reggio, my friend Carmelo Nucera and his Apodiafazzi Association are also teaching the language. This too warms my heart as I see the language remaining in the most important city in Calabria, led by a group of people who are passionate and who over the years stayed in touch with me, always encouraging me to return.

When we finished our meal, and asked for the bill, the Nucera family replied with “Pay whatever you wish!” This is the first time I had come across this approach anywhere in the world, and I have been to over 50 countries. The meal and location were essentially priceless.

Danilo had of course one task for us which was set by Maria Olimpia Squillaci, to make sure we returned to the coast at Bova Marina by 4.00 pm as a group of children from Palizzi village, with their parents and teacher were waiting to sing us songs in Greko and to swap letters and cards of well wishes. These cards and letters were provided from students in two countries. The first from Australia, with UNSW Modern Greek Department via Dr Efrosini Deligianni in Sydney and Oakley Grammar in Melbourne, from teacher Natasha Spanos. Both had enthusiastically embraced the chance for their students to connect with Greko students and speakers. The second coming from my friend and teacher in Thessaloniki, Christina Michailidou, from Δημοτικό Σχολείο Νέας Ραιδεστού. A gesture that will be remembered by the recipients in Calabria.

One of the villagers somehow tricked me into taking a ride on his scooter and to another hidden piazza, where various generations of Greko speakers were playing music and dancing. When I noticed Danilo and Basil turn up, I felt a quick getaway looming, instead, we all joined in another round of music during what can only be described as Greek time, with 4.00 pm approaching and the kids from Palizzi almost certainly waiting!

Eventually, I was able to usher us out of the piazza and to the waiting car for a drive down the mountain past the old dried river that once connected dozens of Greko towns. The river may have dried up, though the spirit of Greko and the language never will. As long as there are people who can speak the dialect and enough people who care about the Greko villages, then these statues will remain on speaking terms with the rest of us for millenia to come.

For more information on how to help save the Greko language, visit https://buonacausa.org/cause/se-mi-parli-vivo

Note: There are a number of groups in Calabria all working towards preserving the language, including Apodiafazzi.

* Billy Cotsis is the the author of the ‘Many Faces of Hellenic Culture’.