Mikis Theodorakis’ career as a composer began in the early 1940s in the Arcadian city of Tripoli. Back then, he wrote hymns for the Greek Orthodox Sunday liturgy at the Agia Triada church, including his two most significant works from this era, the evocative “Hymn to God” and the “Kassiani” liturgy. Just like the approximately 30 other liturgical cantatas from this period, these were based on the writings of Greek Orthodox church fathers resp. the priestess Kassiani.

As a grammar school student in Tripoli, Theodorakis attended the seminars of Evangelos Papanoutsos, the most prominent Greek philosopher of his time. During his studies under Papanoutsos, the young Theodorakis discovered and developed a passion that remained with him to this day: a deep and pronounced love of the foremost authors of antiquity.

Perfectly versed in ancient Greek, the youngster decided to devour anything antiquity had to offer in terms of the written word. Not just the tragedians, but also all of the period’s philosophers, mathematicians and astronomers. From the words of Pythagoras’ disciple Philolaos, Theodorakis gleaned that the distances between the planets could be determined by their relationship to the “central fire”, ie the universe’s core of fire, also known to Philolaos as the “mother of gods” or the “altar” and “order” of nature, the universe’s pivot and centre point for the cyclical turnings of: the anti-earth, the earth, the moon, the sun, the planets and – finally –, in the outermost spheres of outer space, the “unsteady firmament”. To the pre-Socratian, fire was the origin of light and the ultimate source of the absolute’s energy. According to Philolaos, fire and music were gifts to humankind.

In his words, music – as an expression of the planetary sound on earth – triggers an echo of the universe, and this reverberation moves people into a purely spiritual state, a shift similar to the way that fire – on the material plane – serves to purify our terrestrial spheres. These thoughts and ruminations deeply inspired Theodorakis and provided a foundation, building block and starting point for the development of his subsequent theory of Universal Harmony.

READ MORE: A poem for Mikis Theodorakis

Theodorakis’ penchant for the pre-Socratians and their music and numbers theory had its origin in the multitude of nights the 5-year-old Mikis spent sleeping under the starry sky on the Aegean island of Chios. Nights, in which his father spent hours on end – over the course of many months – explaining the mysterious firmament above. Impressed and influenced by this majestic celestial order, the child soon began to notice the dichotomy between micro- and macrocosm, between chaos and harmony. Idyllic safety within his close-knit family versus danger and pain outside this safe haven. And later on: peace within, death and torture without.

In an essay from November 2006, Theodorakis who, as a composer and ever since early childhood, experienced “sound” as the cause of musical creation, drew attention to a particular aspect of reception and composition: According to him, it takes only a tiny step from pre-Socratian thinking on harmony and the music of the spheres to his own perception, to his experience of hearing an overwhelming sound within himself before it takes the shape of music. To Theodorakis, both aspects are two sides of the same coin – and the second is just a manifestation of the first: earthly music as a mere reflection of the sound of the universe.

In 1943, the 18-year-old Theodorakis joins the Athens Conservatory with his “Symphony No.1”, an oratorio based on his own words. In this work, he splits his religious-inspired quest for good into the duality – exemplified by the use of an equal address – of light and dark. Thus, begins his life and career as a composer.

READ MORE: Greece mourns the passing of legendary composer Mikis Theodorakis, aged 96

International Acclaim

In 1958, ie 15 years later, Mikis Theodorakis is counted amongst Western Europe’s key young composers and most successful rising stars of so-called serious music. In the same year, his two ballets at the Sarah Bernhard Theatre in Paris meet with a rousing response, causing a Le Monde music critic to hail Theodorakis as “possibly the new Stravinsky”. These ballets, performed by Ludmilla Tcherina, win him a commission by the Royal Ballet at London’s Covent Garden. The subsequent “Antigone”, choreographed by John Cranco and performed more than 150 times, catapults Theodorakis into the international arena and wins him great acclaim as a classical composer.

Benjamin Britten lauded his young Greek colleague in several newspaper interviews. Darius Milhaud suggested him for the American Copley Prize 1959, awarded to the best European composer – and indeed received by Theodorakis. A year earlier, he had already won the Moscow Composer’s Competition’s Gold Medal for his “1st Suite for Piano and Orchestra”, an award presided over by jury head Dmitri Shostakovich and his deputy Hanns Eisler. Four years later, Theodorakis received the Sibelius Award for his symphonic works from a jury comprising Pablo Casals, Zoltan Codaly and Darius Milhaud.

Furthermore, in the three years between 1958 and 1960, he rose to broader international fame thanks to a string of signature film scores for, among others, Michael Powell, Jules Dassin or Anatole Litvak and movies starring Anthony Perkins, Melina Merkouri and Ralf Valone. At this point in time, there was no doubt that a grand international career awaited the composer Mikis Theodorakis. And there was no inkling on the horizon that he might turn to writing “mere” songs.

READ MORE: Maria Farantouri visits Australia with Israeli tenor Assaf Kacholi in tribute to Mikis Theodorakis

Re-embracing his Roots

Against this background, Theodorakis’ return to Athens in mid-1960 seems all the more surprising and dramatic, especially considering his simultaneous and uncompromising renunciation of so-called serious music. At a stroke, he bid farewell to the fame and success of Paris or London and – for the subsequent two decades – focused solely on so-called “contemporary folk music”. To some extent, the reasons for this abrupt change boil down to a single, yet vital question: Who do I compose for? Who is my partner in dialogue? On the other hand, Theodorakis’ biography during the 1940s holds another key, ie his engagement with the leftist EAM movement and resistance against the Italian and German occupying forces and, later on, against the British occupation and monarchist government during the Greek civil war between 1946 and 1949.

During this time, Theodorakis had experienced firsthand how his compatriots constituted a “common people” and thus became partners in dialogue for many artists. Furthermore, and ever since his early brushes with antiquity, he had toyed with the ideal of the Athenian polis model of free citizens who not only founded and lived the notion of democracy, but also served as equal partners for their era’s great artists. In the Athenian polis of Sophocles, Euripides or Aeschylus, the question as to whom their writing addressed had finally been answered. In conversation, Theodorakis likes to refer to the latter’s tombstone inscription, requested by Aeschylus himself. According to legend, he did not want to be known as a great author, but instead as a citizen of Athens who had taken part in the battle of Marathon against the Persian invaders.

In 1960, Theodorakis found his ideal recipient or dialogue partner by swapping the aristocratic-bourgeois audiences of Paris and London for a broader public in Greece. And during the early 1960s, this phenomenon – to some extent nourished by the cultural revolution launched by Theodorakis – indeed shaped the initially amorphous mass into something one might call a historically acting subject “folk/people”. And yet, this exciting and dynamic process did not last very long. In 1967, a coup by a CIA-masterminded Greek junta led to the establishment of the only Western European military dictatorship after the Second World War. For a brief time only, the politico-cultural movement initialised by Theodorakis, institutionalised in 1963 via the Lambrakis Youth Movement, managed to strengthen and bolster a left previously demoralised by the civil war, helped it to gain new strength and confidence and finally, motivated by the – according to Theodorakis – “Holy Triad” of poetry, music and political emancipation, reclaim vitality and political power.

READ MORE: Romiosini And Beyond: A musical event celebrating Greekness and Mikis Theodorakis’ oeuvre

What, however, brought all this about – and what exactly happened in this early autumn of 1960? Two years earlier, Mikis Theodorakis, then 35-years-old, had set some lyrics by his friend, the poet Yannis Ritsos, to music and forwarded them to fellow composer Manos Hadjidakis in Athens. Hadjidakis, back then, was considered the undisputed master of Greek songwriting. Together with his muse and singer, Nana Mouskouri, Hadjidakis enjoyed great success and soon received an Oscar for his “Never on Sunday” soundtrack, a film starring Melina Merkouri. Manos Hadjidakis wanted to help his friend find his feet in the Greek music scene after his return to his native country, so he offered to arrange Theodorakis’ eight Epitaphios songs based on Ritsos’ lyrics and then record them with Nana Mouskouri – a truly wonderful and open-hearted gesture. In September 1960, Manos Chatzidakis went on to orchestrate these songs and started to capture them on tape for later release with his musicians, Nana Mouskouri and himself on piano. Truly overwhelmed by this genuine sign of friendship, Theodorakis attended all practice and recording sessions in the studio. After three or four songs, however, he began to realise that this take on his own music did not actually match the new aesthetics brewing inside his head. After all, Theodorakis had not abandoned his symphonic career for a switch to mainstream pop, no matter how excellently orchestrated. He wanted to create something entirely different, something entirely new.

Twelve years earlier, on the concentration camp island of Makronissos, where he had undergone one of his toughest hardships of his life as a 23-year-old prisoner of war, he had overheard a soldier sing. What he had heard was a rough, unsophisticated voice, one that – in Theodorakis’ mind – had nothing in common with the notion of “high art” or any obvious artistic ambitions, but a voice and tone destined to express the desire, authenticity and survivor’s spirit of the common people. Through the universal language of music, Theodorakis wanted to build a bridge between himself and the soul of his Greek compatriots. And he displayed an incredible knack for translating this unique yearning into musical expression.

Theodorakis sought and found Grigoris Bithikotsis, the former soldier from Makronissos, who by 1960 had gone on to sing his songs in tavernas. At the same time, Theodorakis also engaged the period’s best-known bouzouki player, the virtuoso Manolis Chiotis. Together with several other musicians, the composer, singer and instrumentalist went into their record company’s studio (Columbia), and while Hadjidakis continued to put the finishing touches to the last title with Nana Mouskouri at Fidelity Records, Theodorakis recorded all eight songs from scratch, only this time with Bithikotsis and Chiotis – thereby giving life to his vision.

This was the birth of a new style of music and a brand-new flavour of Greek culture comparable to “The Beatles in Greek”. Both records saw the light of day in October 1960. The same songs, the same lyrics by Yannis Ritsos – one arranged by Manos Hadjidakis and sung by Nana Mouskouri, the other arranged by Mikis Theodorakis and performed by Grigoris Bithikotsis. What happened then might be a first in musical history: Music critics were unanimous in their praise of Hadjidakis’ version and their disdain for Theodorakis’ efforts. The right-wing government banned the songs’ broadcast on Greek radio because they would spread “communist contents”. And the left, too, home to both Yannis Ritsos and Mikis Theodorakis, vehemently opposed Theodorakis’ version. One critic, A. Eleftheriou, even wrote of a “small civil war”. After a few weeks, however, not a single Greek on the streets did not know the songs sung by Bithikotsis and did not belt them out himself. It was a miracle. Theodorakis’ release broke all records. The well-known poet’s verses – written in a strict metric, the decapentosyllab –, which in an analogy to Mary’s crying over Christ expressed a mother’s sorrow for her dead son, were on everyone’s lips. And Theodorakis’ song cycle followed the example and structure of a Schubert song cycle.

READ MORE: Composer Mikis Theodorakis slams Tsipras over Macedonia name dispute resolution

During the subsequent months, Theodorakis set countless poems by his country’s most prominent lyricists to music – including those by two later Nobel Prize winners (Seferis and Elytis) – and thus “brought poetry to the common people”, as Yannis Ritsos wrote back in the day. Within a mere six years, Theodorakis had composed around 500 songs, all of which were eagerly welcomed by the Greeks and became part of their cultural identity. According to Ron Hall, “it was as if Benjamin Britten had turned Auden’s verses into songs and then his record – featuring vocals by the Archbishop of Canterbury – had kicked the Beatles out of the Top 10”.

From his Music Springs a Nascent Cultural-Political Awakening and Identity

The aura surrounding this new cultural movement thus fed on poetry, music and the irrepressible and absolute claim to self-determination and individuality. This musical revelation of an entire generation’s innermost feelings made Theodorakis’ personality and songs an integral part of the soul of each and every Greek who had until then been silent.

What developed and evolved in Greece between 1960 and 1967 was something so extraordinary that it is worth taking a closer look. The history of the 20th century’s new and emerging Greek nation was characterised by its gradual territorial constitution and foundation, an extreme political polarisation, several wars and a civil war. After the Balkan Wars, the Great War, the 1922 catastrophe in Asia Minor, the Metaxas dictatorship 1936, the Second World War, the civil war (1946-1949) and the subsequent military state under emergency law, Greece only experienced a slow return to normal from the late 1950s and only began to settle and consolidate in the early 1960s. The military coup of 1967, however, signified an abrupt end to this brief initial and somewhat democratic phase in the history of the young Greek nation – with disastrous consequences for the country’s societal and cultural development. To this day, Greece remains a special case: It was the only Western European nation to install a military dictatorship two decades after the Second World War, a dictatorship lasting seven years. Neither NATO nor Greece’s Western European partners or its allies in the USA were prepared to play their part in aiding the swift removal of the military regime. Instead, all of them accepted the dictatorship, a regime governing a people who – for the first time in modern history – had been privileged enough to enjoy a fleeting touch of democracy.

During the second half of the 20th century, the country’s national identity had, most of all, been defined via the cultural identity of “Greekness” (Romiosini). So, it is only apt and symptomatic that in the 1960s – during a terribly brief democratic respite of seven to eight years – a culture with enormous international appeal began to flourish, a culture that continued to influence the artistic and aesthetic concept and self-image of most Greek creatives well into the 1990s. At the same time, this takes on culture met with a phenomenal response from all social strata. And that is not all. “Greekness” not only entailed a frequently recurring enthusiasm for antiquity, but also encompassed sophisticated modern culture. Greek artists developed international careers and soon rose to global fame. In a way, it almost felt as if Greece had suddenly decided to make up for time lost since the European renaissance and caught up to the world in record time. This particular cultural movement suffered heavily under the seven-year dictatorship and the era finally drew to a complete close in the early 1990s. It had lost its epigones and – in a slow, almost imperceptible process – was replaced by a cosmopolitan, often indifferent cultural landscape that increasingly lost its national characteristics. Ever since, most of the great art by Greek artists has come from the Greek diaspora in the USA, Australia and Europe – external outposts that harbour as many Greeks as their country of origin and play host to the likes of Jeffrey Eugenides, Alexander Paine and Aris Fioretos, for example.

READ MORE: “Memories of Dictatorship”, a Greek Film Archive Tribute for Greeks worldwide

This – in my thoughts and words – “New Golden Age”, these Golden Sixties of Greek culture, constitutes a phenomenon that has left its mark on all artistic disciplines, on literature, music, fine arts and cinematography. One of the period’s undisputed highlights remains the Nobel Prize for literature, awarded to Giorgos Seferis in 1963, while fellow writers and poets Odysseas Elytis (who received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1979) and Yannis Ritsos continued to rise in international significance. This brand of new Greek literature – best known across the world for the novels of Nikos Kazantzakis – soon transcended national borders and was translated into many languages. In terms of music, Manos Hadjidakis caught the limelight in 1960 when he received an Oscar for his soundtrack composition. Mikis Theodorakis, too, enjoyed growing popularity for both his symphonic works from the 1950s and his later song cycles. Also during the 1950s and 1960s, several Greek film-makers received Oscars or other awards for their work in Los Angeles, Cannes, Berlin, Paris, London etc., among them masters of their art like Michalis Cacoyannis, Nikos Koundouros, Vassilis Photopoulos and others. During the 1960s alone, Greek films or actors were honoured with a total of 16 Academy Award nominations, more than in any preceding or subsequent decade. Works of fine art – e. g. those by Yannis Tsarouchis – entered the collections of the Louvre in Paris and the portfolios of other name collections and museums. Back then, several Greek artists were still at the beginning of their ascending and international careers (Constantin Costa-Gavras, Theodoros Angelopoulos, Yannis Kounellis, Vangelis, Olympia Doukaki, Petros Markaris), while other well-known and feted personalities had already reached the peak of their fame. Who could forget Maria Callas, Melina Merkouri, Dimitris Mitropoulos, Yannis Xenakis, Irini Pappas, Katina Paxinou, Nana Mouskouri and – not to forget – John Cassavetes or Elia Kazan (both with Greek roots), to name but a few?

This cultural boom and bloom of a new Greek nation during the 1960s had its roots in the 1950s. Back then, both the disillusioned and traumatised leftist intelligentsia and the so-called bourgeois artists defined their artistic identity and aesthetics via the relationship to:

1. recent Greek art, i. e. since the 19th century (e. g. the “discovery” of Makriyannis’ memoirs, Theofilos’ naïve paintings, Karagiosis’ puppetry and “alternative” Rembetiko music)

2. European Modernity (e. g. the ostensibly revolutionary tradition of Sovjet novels, French surrealism, modern ballet and New Music) and

3. antiquity (e. g. on the one hand the aesthetics of Laconian Constantinos Cavafys, on the other the anthemic Angelos Sikelianos).

At the same time, the Second World War and, most of all, the subsequent civil war and their psychological processing, assimilation pressures and repression played a decisive role as aspects of an almost imperceptible reflection, an almost never openly discussed and yet clearly existing traumatic experience anchored in the collective subconscious. Yet another fact held equal importance: All of the above-mentioned artistic processes took place under a latent, yet ever-present diasporic reality of “Greekness”, a reality thrown into sharp relief by the dramatic repercussions of the 1922 catastrophe in Asia Minor and the final loss of Constantinople. If you expand these observations to include the aftermath and repercussions of the Cold War and the peculiarities of both pro- and anti communist propaganda in Greece, the context of the developing cultural and national self-image becomes even clearer.

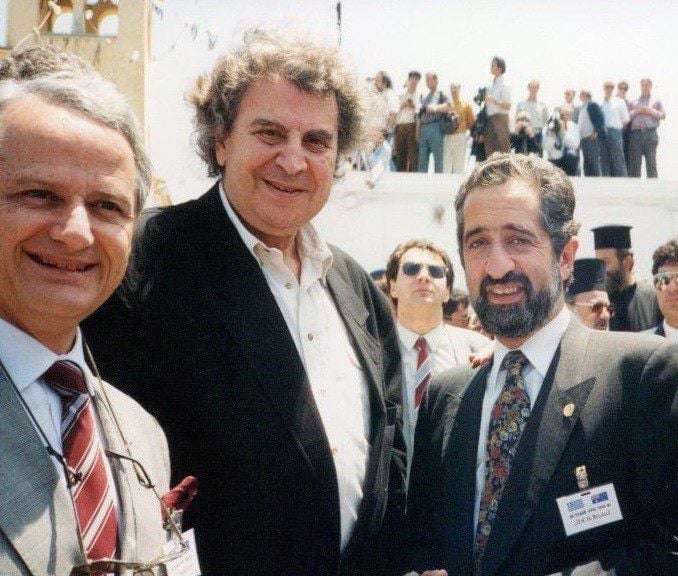

Mikis Theodorakis at a rally. Photo: Angelos Giotopoulos

Music composer Mikis Theodorakis holds a baby at the Aristotle Square in the northern port of Thessaloniki, Wednesday, June 8, 2011. Theodorakis, who won an Academy Award for his score in the film Zorba the Greek, is angry at municipal authorities' refusal to let him use Thessaloniki's central Aristotle Square for an anti-austerity protest Thursday. The municipality asked Theodorakis to choose another square, arguing that his protest would cause unnecessary disruption in the city's commercial center. The composer has refused, accusing unspecified 'dark forces' of conspiring to stop the gathering. Photo: AAP via AP

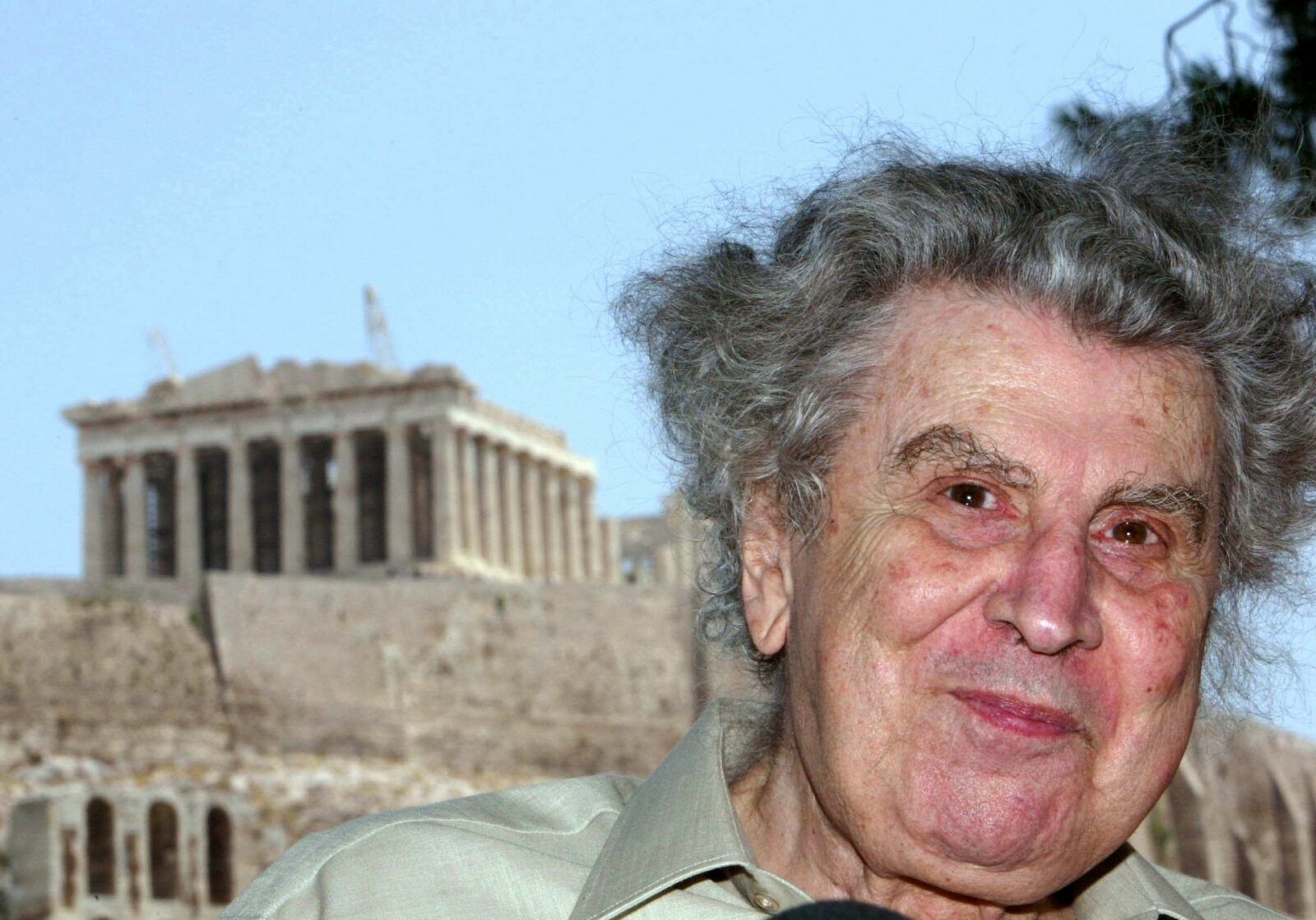

Mikis Theodorakis, the beloved Greek composer whose rousing music and life of political defiance won acclaim abroad and inspired millions at home. Photo: AAP via AP/Petros Giannakouris

Greek composer Mikis Theodorakis attends a press conference in front of the landmark Acropolis hill in backround, in Athens, Greece, 15 June 2004 (reissued 02 September 2021). Legendary Greek composer, musician and politician Theodorakis passed away on 02 September 2021 at the age of 96, according to the Greek Culture Ministry's social media site on 02 September 2021. One of Theodorakis' most popular works was the soundtrack for the 'Zorba The Greek' movie from 1964 with Anthony Quinn. Photo: AAP via EPA/Paris Papaioannou

Dissolution of the Voice of the People and Return to Symphonic Form

The 1967 coup was not only meant to prevent the anticipated phenomenal electoral success of the liberal Center Union (Enosi Kentrou), a group hardly threatening to the governing system, but most of all a reaction to precisely this cultural revolution promoted and embraced by wide swathes of society, especially its younger constituents, and suffused by a leftist-libertarian and simultaneously enlightened and educational spirit. So, although the cultural tradition of the Golden Sixties continued to reverberate well into the 1990s, it was – as mentioned above – brutally suppressed by the seven years under Greece’s junta regime and subsequently, from 1974, actively fought by the governing parties and – due to its implied postulate of freedom – even to a certain extent by the Communist Party.

The junta interrupted both the movement’s emancipatory process and its artistic dialogue, thus dissolving “the people” as a subject of history. Theodorakis’ attempts to rekindle this “dialogue” after the fall of the junta in 1974 invariably came to nothing. Once he was left without a partner in dialogue, he recently stated in an interview, the only conversational partner that remained turned out to be himself. And so, in 1980, he once again returned to his Parisian lair to launch a musical dialogue with himself, leading to the composition of his second, third, fourth and seventh symphonies, to an artistic worldview he likes to call a “lyrical life”. A stance and philosophy that, incidentally, also introduced him to the world of opera, a realm he now knows as “lyrical tragedy”.