My dear mum Efstathia Spiropoulos was born in a small village called Flessiada, on the outskirts of Kalamata in the Peloponnese on 10 June 1920.

The village, being high in the mountains was very isolated and as a result the people were very self-sufficient. They grew their own vegetables and made their own soap, cheese, yogurt, preserved their meat, cured their olives, dried their figs, made their own pasta and even made their own household linen and blankets. The entire village had looms and the young ladies were busy weaving linen and blankets for their dowries.

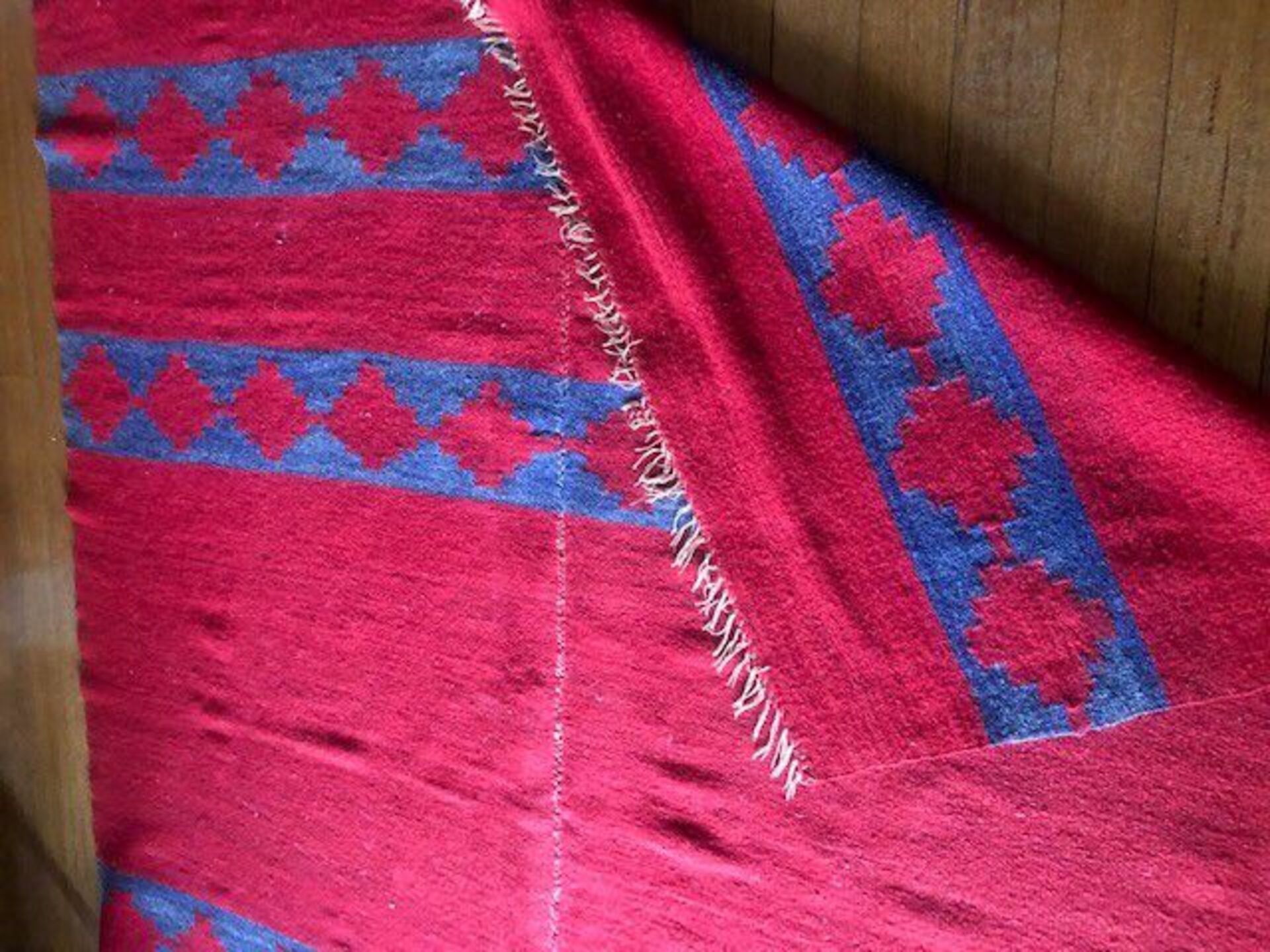

This blanket (pictured here) is one that mum wove for her dowry circa 1939 just before World War II when she was eighteen or nineteen years old. It was brought to Australia in 1964 when mum and dad, together with their seven children migrated to ‘the lucky country’ down under on the PATRIS. We stepped onto Station Pier in September 1964 excited and frightened at the same time. To make the blanket, mum first had to shear her sheep, wash the wool fibre and let it dry. Then she had to tease the wool using teasing brushes or hand carders removing any debris and making it light and fluffy ready for spinning. In Greek the hand carders are called ‘Lanaria’ plural or ‘Lanari’ singular.

The wool was hand spun into yarn using distaffs and drop spindles. The distaff is a stick or spindle on to which wool is wound for spinning but unlike today, where you can purchase a nice distaff or drop spindle, the resourceful women of that generation cut branches, made it smooth to touch and used that for spinning.

Spinning was a constant task in her daily life. Every spare moment she had was spent spinning in order to amass enough yarn to weave her blankets. Hand spinning was a time-consuming task especially considering that a woman, even a young lady like herself had to take care of the younger siblings as well as the elderly grandparents living with them. She also worked out in the fields and tended to the animals that were essential to their livelihood. When she was a shepherdess she would make sure she had her hand-woven sack carrying her teased wool on a distaff and her spindle ready to go.

While the sheep grazed my dear mum would pass every second of her time spinning. It was automatic to them. When she brought the sheep back, milked and settled for the night and all her chores completed she would continue her spinning. Mum would often tell me, in her day, a young lady was never idle especially when there was spinning to be done.

Once enough yarn was accumulated the next step was to dye the yarn. The women dyed the homespun yarn with dyes purchased from peddlers or made their own dye from natural products such as walnut husk, beetroot and brown onion. Sometimes she would walk through mountainous terrain to the nearest town ‘Chora’, three hours away, to purchase the dye from the shops where there was a greater variety of colours. Mum often chose red and blue dyes for her blankets.

This one was also made from wool sheared from her sheep, washed, teased and hand spun into yarn that was dyed red and blue, woven on a wooden loom in two identical panels the width of the loom and then joined with great precision to align the patterns and make it large enough for a blanket. Each panel is approximately 87cm and once joined it is 174cm wide and 210cm in length.

The patterns consist of four blue segments each 18cm wide, two on each end of the blanket running the width of the blanket. There are red geometric shapes within the blue segments, five shapes on each panel making a total of ten geometric shapes matching perfectly across its width in all of the four blue segments.

When asked where she got the patterns from, mum replied that they made their own patterns. She did mention though, if they liked a pattern they saw on a blanket belonging to their grandparents, friends or relatives they would count the threads and copy the pattern for future use.

Once the yarn was dyed, dried and the pattern selected the weaving was set to begin.

The weaving loom ‘aryalio’ was wooden and bulky and took up a lot of space in the small house in the village. During the summer months the loom was set up outside to make it easier. Mum would say that women wove only after working in the fields all day, tended to the livestock and completed all the daily household chores. Only then, were they free to start their weaving. She says that she would frequently stay up until very late, weaving using an oil lamp ‘Lihnari’ to complete a section. She toiled for many hours making these precious hand-woven items. One particular night she was determined to finish a piece and literally stayed up all night when her aunty rushed through the door saying “The Germans are here! Run Efstathia! Run to the mountains and hide.” And she dropped everything and ran for her life.

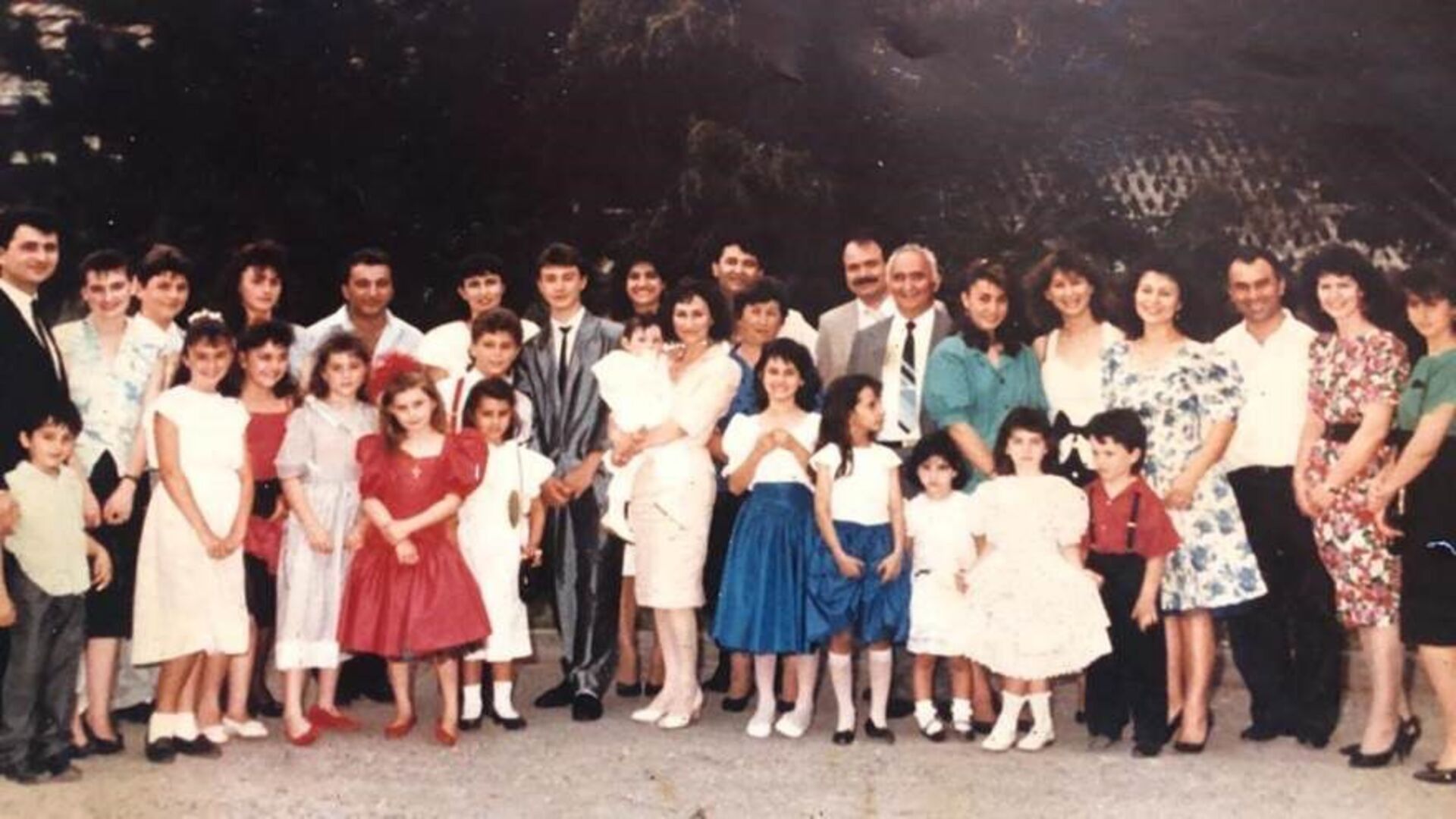

With the German exodus at the end of World War II, Greece was immediately embroiled in civil war. For four more long years Greece was at war, brother against brother, fighting communism. Mum got married in 1946 and my eldest brother was born 1947. Dad was called to war and mum struggled to make ends meet and care for her baby son.

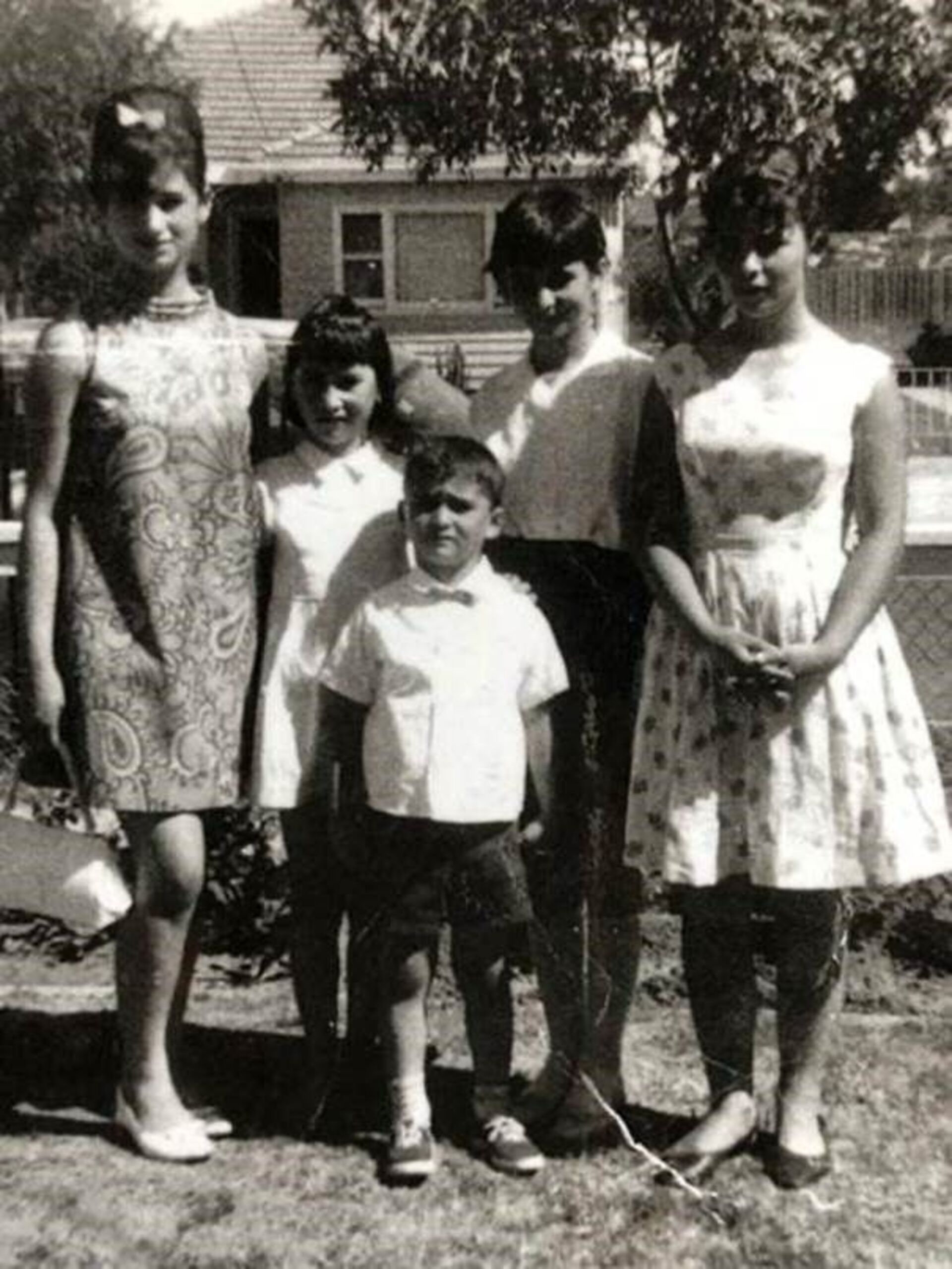

In the 1950’s life began to normalise. Mum had another five children in the 50s and her youngest child Anastasios born in 1962. All seven children were born at home without a doctor, without electricity or running water in the home. It was a difficult life but she always made time for her weaving. She had the dowries of four daughters to think about.

In the 1960’s women stopped weaving. Instead they took the fleece to the mill where it was spun and made into blankets for them. The industrial age had begun for this small, mountainous village in the Peloponnese. Mum still has many of these factory-made blankets neatly stacked on top of the ‘baoulo’.

This particular blanket that mum wove in her teenage years is very special to us. It reminds us of mum’s youth and the difficult life she lived. It has survived throughout the years due to the special care she always took with her things. When you grow up with so little, you treasure what you have.

In our home these special hand-woven blankets were folded neatly and placed in a large storage trunk called a ‘baoulo’. When the trunk was full, items of value such as more woven blankets, quilts, ‘paplomata’, fabrics, woven rugs ‘kilimi’, tablecloths and other handmade rugs were folded and layered one on top of the other to form an impressive stack, perfectly aligned to match the exact dimensions of the storage trunk. This carefully folded stack is called a ‘youko’. Mum would often look at the ‘youko’ and marvel at its contents. Together with mum, under her guidance, my three sisters and I would annually air out the precious items and deliberate on how life was and how amazing mum’s journey has been.

* Stavroula Spiropoulos is a reader who submitted her personal story after her mother’s blanket was chosen to be exhibited at the Open Horizons: Ancient Greek Journeys and Connections exhibition