One of the benefits of re-visiting famous museums or art galleries is the opportunity of catching a significant temporary exhibition. So what a wonderful surprise it was for me to come across the centenary exhibition of some of the major works of artist John Craxton during my recent visit to the iconic Benaki Museum in central Athens.

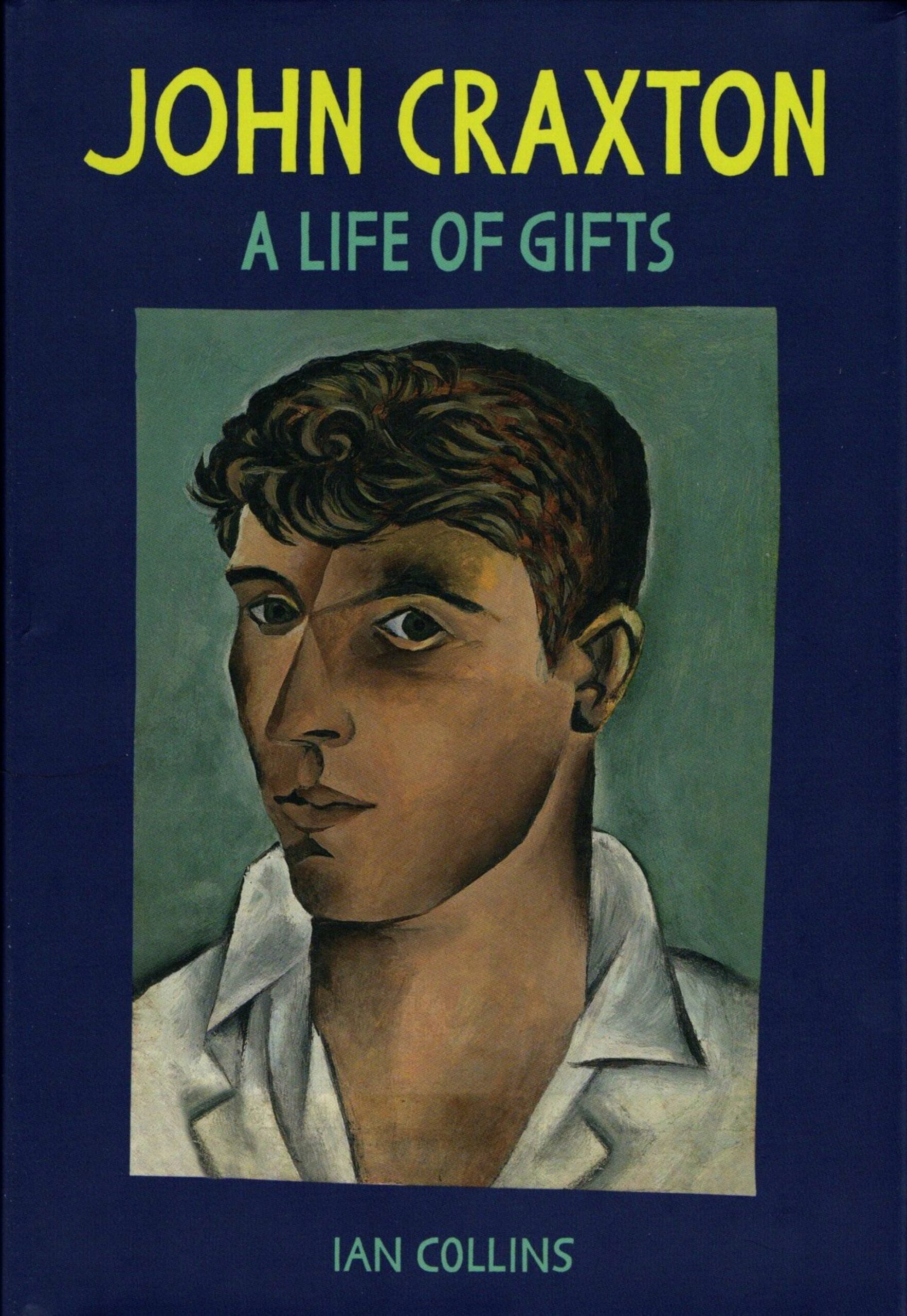

The exhibition encompasses some 90 exhibits, drawings, paintings, weaving designs as well as book and record cover illustrations. The website for the exhibition contains much information as well as a short video presentation (see below). The exhibition has been curated by John Craxton’s biographer, Ian Collins.

For those who don’t know of John Craxton he is a very significant member of that group of post-WW2 western artists, writers and musicians who were attracted to Greece, its culture and environment. He was a friend of British philhellene’s and long-time Greek residents Joan and Patrick Leigh Fermor as well as Leonard Cohen during his sojourn on Hydra.

Most significantly John was also friends with the Greek artist Nikos Ghika and the Noble Prize-winning poet George Seferis. He would also assist the famous Cypriot film-maker Michael Cacoyannis in finding locations for his film production of Zorba the Greek. He met a number of other famous individuals while in Greece, the dancer Margot Fonteyn as well as Winston Churchill, the latter with whom he discussed painting. These are just a few of John’s connections in Greece. I have always been fascinated by the post-war artistic colonies in Greece – and so it is always a pleasure to come to appreciate another component or angle in the creative hotbed.

John Craxton was born in London in 1922, to Bohemian parents who were both skilled musicians. Although he was never formally trained as an artist, his attraction to art began at an early age and his family and friends exposed him to his first influences. These included the work of sculptors, art collectors (including a collection of the works of El Greco whose work would be major influence on Craxton) and local museums and galleries, which exposed him to Classical sculpture. It was from these sources that his interest in Greece grew.

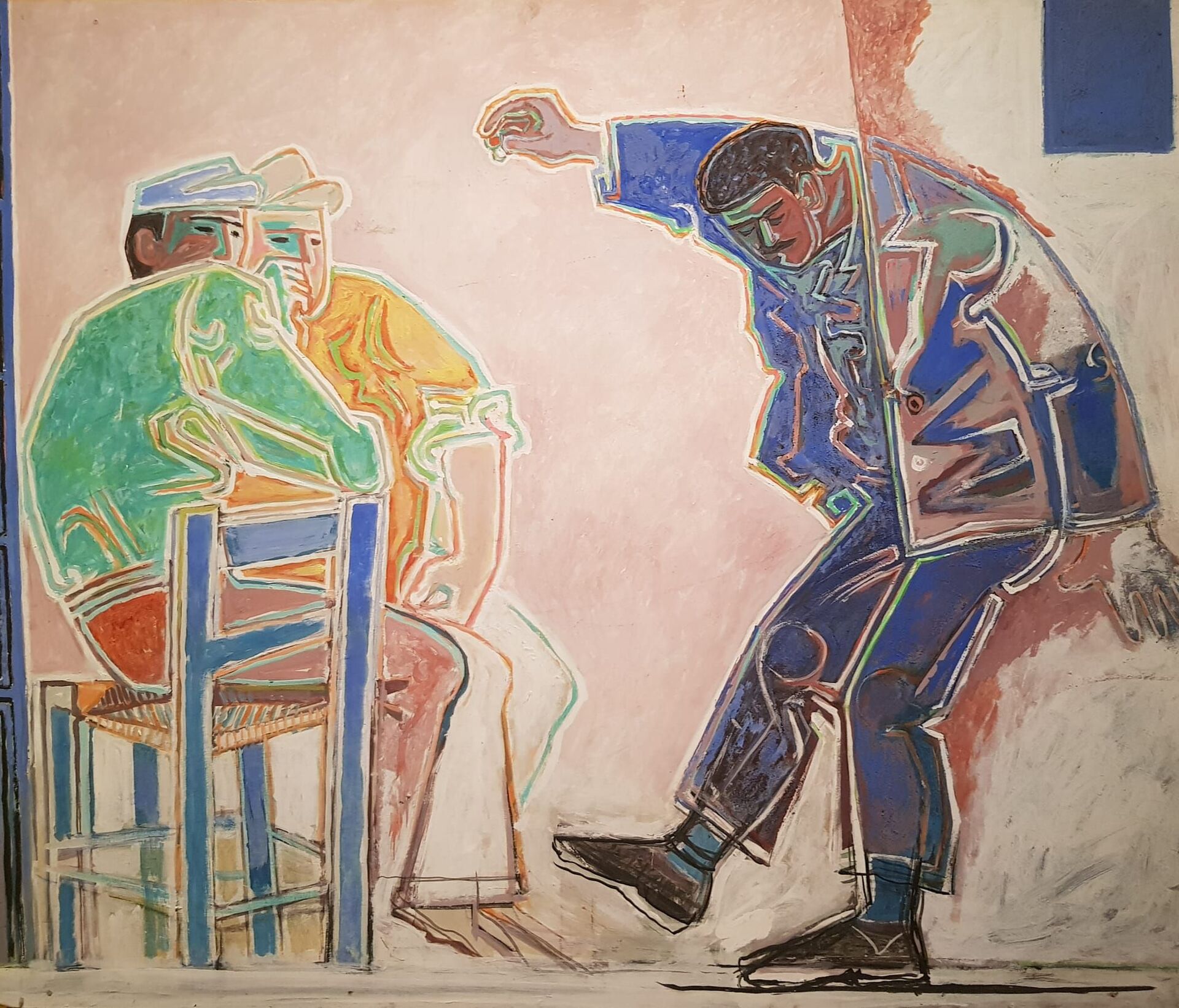

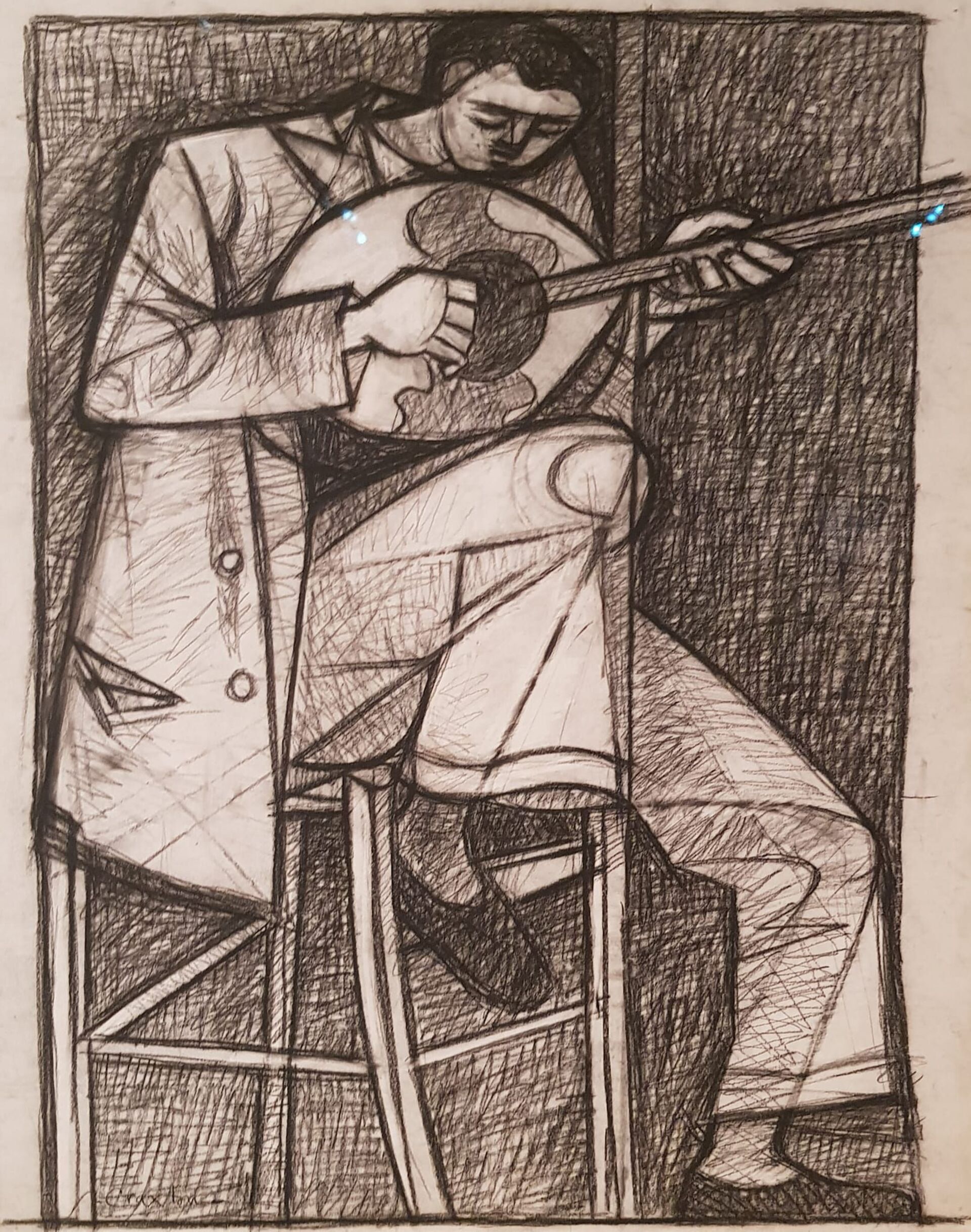

An early trip to Paris was interrupted by the outbreak of WW2. Returning to London, Craxton was soon set up in an adjoining studio to that of his fellow artist Julian Freud. While their early works kicked against the artistic conventions of the day, John’s wartime works were largely dark and lonely pieces. But his fascination with portraits and depicting ordinary life show the direction of his art would take. John Craxton, “Man dancing in tavern”. Photo: Courtesy of Benaki Museum

John Craxton, “Man dancing in tavern”. Photo: Courtesy of Benaki Museum

In what is described as his “Great Escape”, 24 year old Craxton arrived in Greece in 1946 to begin his lifelong obsession with Greece, its people and its environment. His time in Greece would be interrupted by his expulsion during the period of the Greek Junta, his return to Greece with the re-establishment of democracy. While he visited many locations – from Athens to Thessaloniki, Hydra to Poros – it was to Crete that Craxton became increasingly associated. While he would travel over the Island, his base was principally Chania, where he lived in a harbour-side house. He would travel the Island in his motorbike. His second home with views of Crete’s White Mountains has been made a Greek National Monument in his honour.

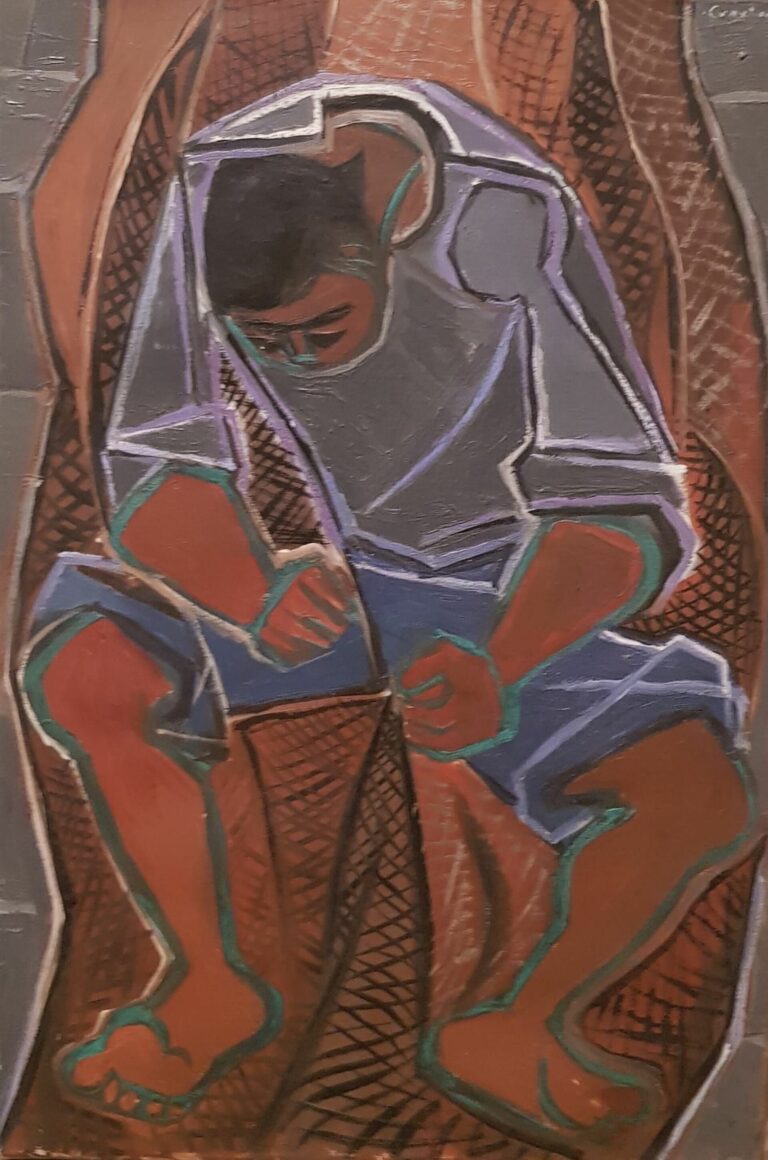

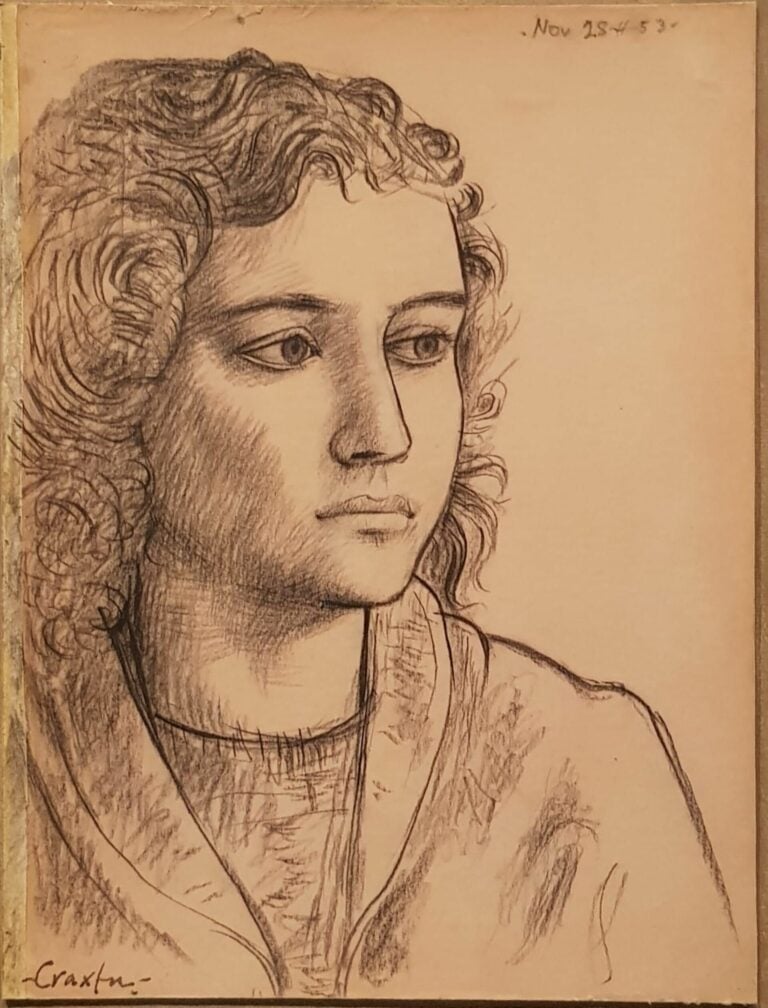

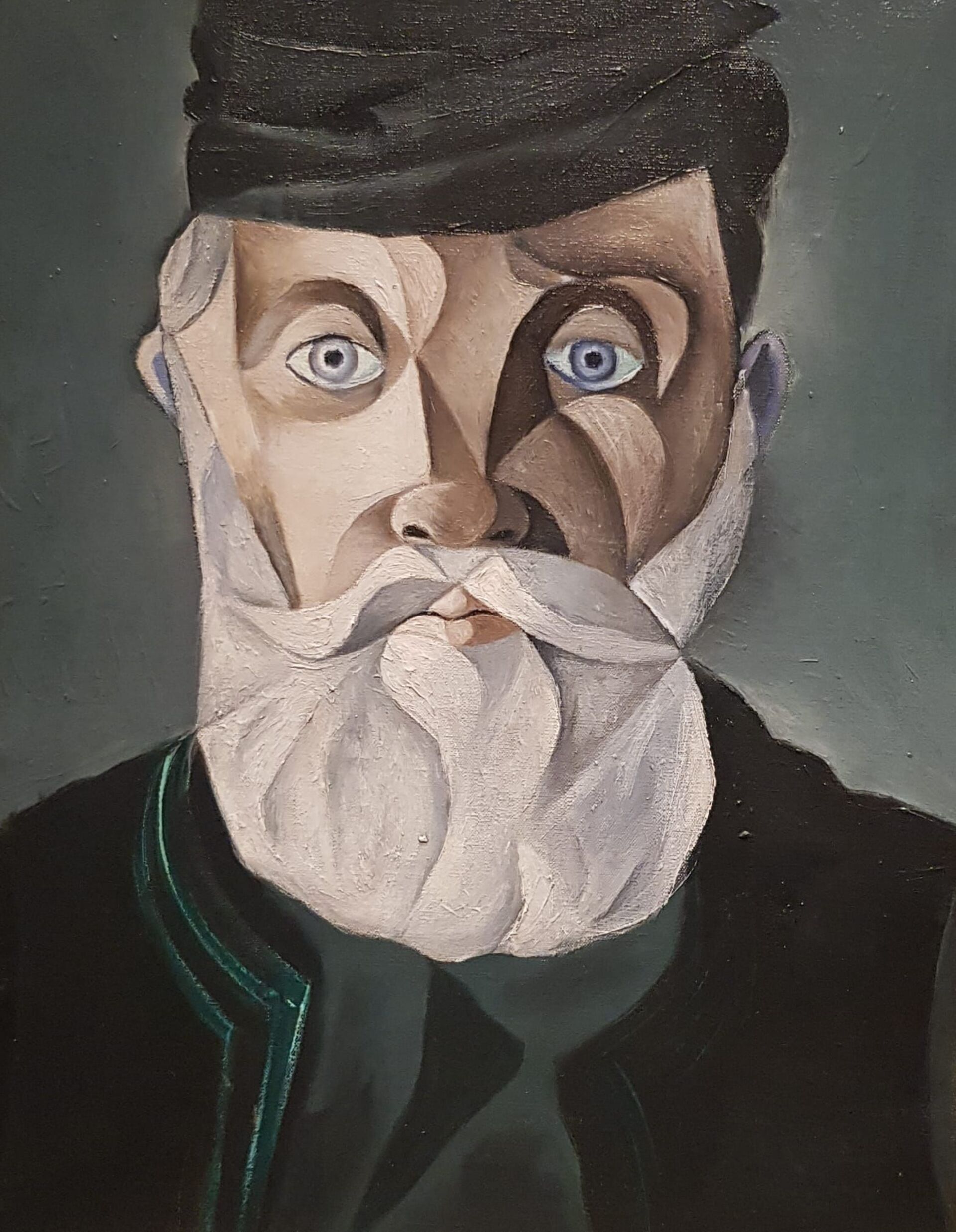

The works from Craxton’s Greek periods can be divided into a series of themes. First we have the many portraits, of young women and girls, of men, sailors and soldiers. Some are fine drawings, others vivid paintings. One of the most striking is titled “Aged Cretan”, (dated 1948). The division of the face into almost abstract blocks of colour is reminiscent of Picasso.

Then there are a series of drawings and paintings depicting ordinary life – fishermen seated repairing their nets, fishermen trying to catch octopus, the fishmonger and his wears and a butcher in his shop, with a large side of beef hanging from its hook. For me the most evocative are those depicting music and dance. We see a beautiful pencil depiction of a bouzouki player in Craxton’s “Musician” (dated 1964), one of a man drinking and two paintings of men in the act of dancing, one titled “Man Dancing in Taverna” (no date). The colours of the latter are vivid and full of movement, the former’s black and white form oozing seriousness and melancholy.

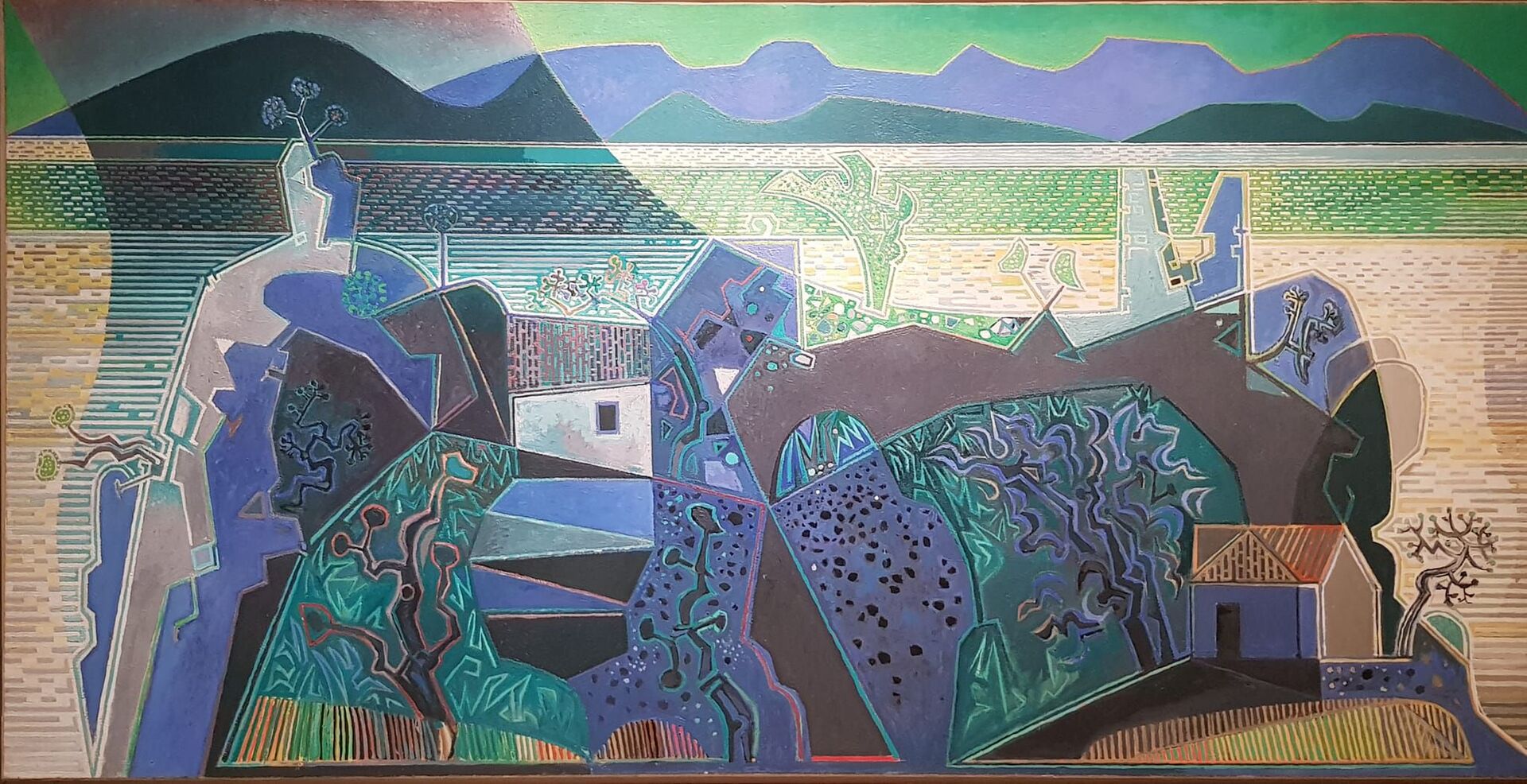

Two abstract landscapes combine environment and figures as if they are both being transformed by the sun, combining in a dash of colours on a hot summer’s day. One is titled “Landscape, Hydra” (dated 1963-67) and the other “Two figures and Setting Sun” (dated 1952-67), the former is from our own National Gallery collection in Melbourne. The light of Greece would find its way into his design for a major tapestry for the University of Stirling, with a dazzling sun, plants and fish, all in a multitude of colours, entitled “Landscape with the elements” (dated 1975-76).

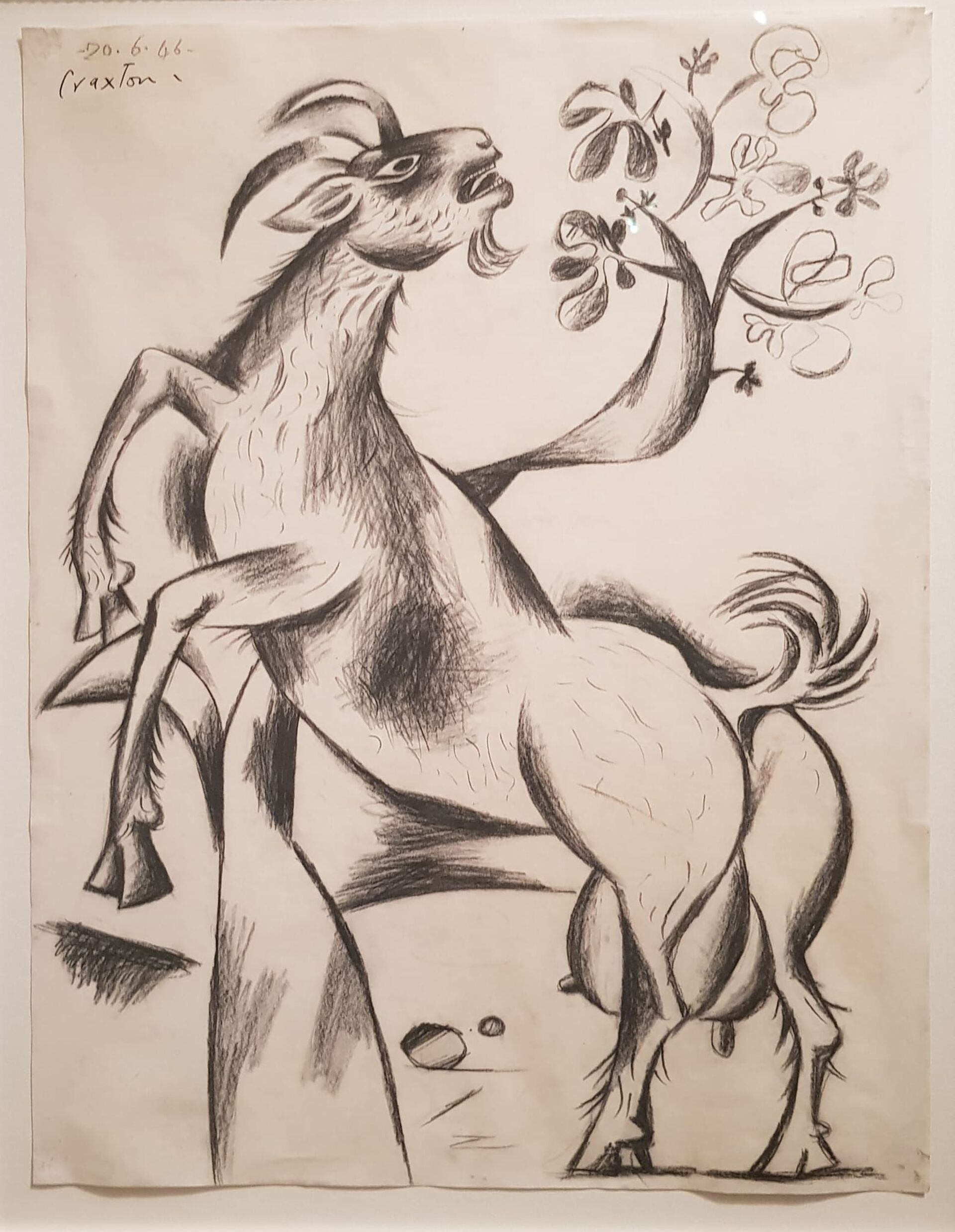

There are a series of other works in the exhibition depicting goats. The exhibition booklet states that he admired the symbolism of goats as embodying resilience and for their connection to Greek mythology (such as Zeus being raised by a goat). Some of his goats are shown extended, at full stretch – such as “Rampant Goat” (dated 1946) – with another straining beneath the power of the shepherd, titled “Voskos”, (dated 1984).

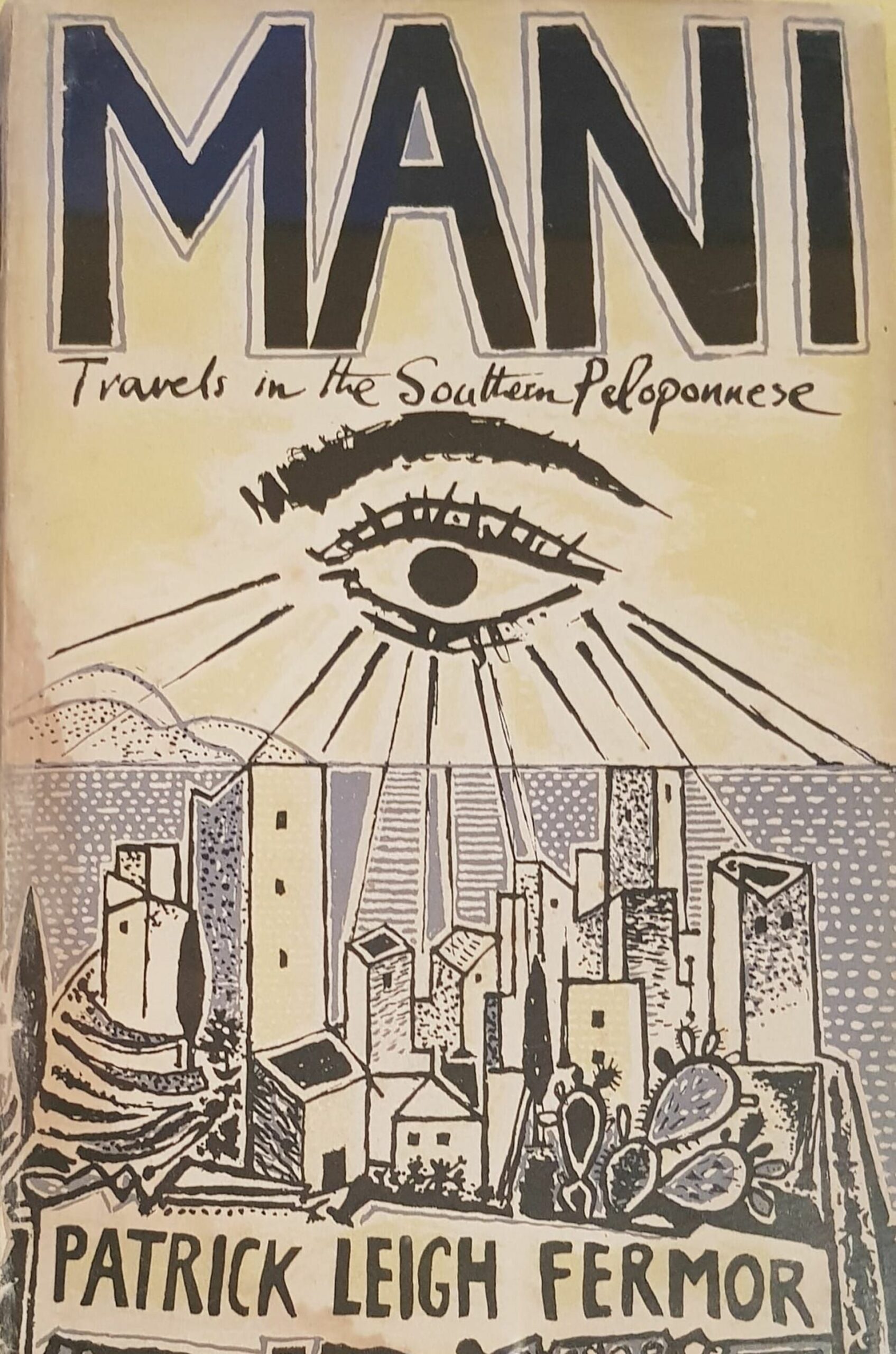

Some may be aware of John’s work as a book illustrator. His good friend Patrick Leigh Fermor chose him to design the covers of his series of travels books, for me the most iconic being the cover of Patrick’s Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese. He also designed the cover for George Psychoundakis’ The Cretan Runner, which was translated and introduced by Fermor. These cover designs reflect the vibrancy of John’s creativity, the few colours being balanced with striking images which catch the eye.

John Craxton’s love of Greece and its central role in his work and life is encapsulated in a quote from him featured in the exhibition. In this he writes: “I can’t tell you how delicious this country is and the lovely hot sun all day and at night tavernas: hot prawns in olive oil and great wine and the soft sweet smell of Greek pine trees. I shall never come home. How can I?”

For anyone who has fallen in love with Greece – or even experienced a hint of this longing during a short trip – what better words to describe the philhellene’s infatuation with all things Greek, from the sublime to everyday. He was certainly in love with all things Greek. As the exhibition states, he may have been a British artist but he had “a Greek soul”.

Initially shunned by the British art world, in later life Craxton’s works would be honoured with a series of major solo exhibitions. He would be admitted to the British Royal Academy of Arts in 1993. John Craxton became ill in 2006, prompting his return to London. He died in 2009, his ashes being scattered in his beloved Chania Harbour.

The Benaki and the creators of this important exhibition of John Craxton and his major works should be congratulated. They have brought together a great collection of his work, spanning his artistic career from his pre-war early beginnings through to the flowering of his creativity in post-war Greece and his return after the fall of the junta. While you might go to our own National Gallery to seek out his image of Hydra, there could be no better way to be given a deeper appreciation of the scale and breadth of his work than by viewing this exhibition.

So if you are one of those who make the regular summer visit to Greece or making your first trip there, I urge you to take time out during your stop in Athens and visit the John Craxton exhibition. You will experience another aspect of Greece’s impact on the modern world – and you won’t be disappointed.

The exhibition includes a beautifully illustrated booklet and a number of copies of John Craxton’s artworks are also available for sale, as well as Ian Collins’ excellent biography – John Craxton: A life of Gifts. The John Craxton Exhibition is currently on display at Athens’ Benaki Museum. It will move subsequently to Chania before its final exhibition in London.

Jim Claven is a trained historian, freelance writer and published author, his most recent publications being Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed and Grecian Adventure, both dealing with different aspects of the Hellenic link to Australia’s Anzac tradition. He also studied fine art at Melbourne’s Monash University. To book tickets, purchase the exhibition booklet or to view a short video on the exhibition go to the Craxton exhibition part of the Benaki website ((https://www.benaki.org/). Jim can be contacted via email – jimclaven@yahoo.com.au