The following is a story written jointly by Sophia Xeros-Constantinides and Miria Cambel (nee Mirianthi Kassianides ‘Cass’) in honour of their maternal grandparents, Bayliss and Evdokia Xeros, and Aristides and Anastasia Kampaklis (Campaclis ‘Camp’) respectively, and their ancestral home of Smyrna – the ‘Jewel of the East’.

‘He who has dwelled there longs for her in other lands and sighs for the vineyards and olive groves, the villas and ruins, the delicious breezes and the star-eyed maidens of Smyrna.’ – SG Benjamin The Turk and the Greek (1867)

Our maternal grandparents were of Greek origin, born and bred in Vourla (now Urla), in AsiaMinor, near the cosmopolitan centre of Smyrna (now Izmir, Turkey). Their families had settled there generations earlier, establishing what would become ancestral homes and cultural heritage, as part of the Greek diaspora extending around the shores of the Aegean Sea.

For Sophia’s grandparents, Bayliss and Evdokia, meeting for the first time was full of promise. When he first set eyes on her, she was alighting from a carriage in the street. Bayliss swore to his friends that one day he would marry her, which he duly did. He owned a shop selling wine, and lived in a house with marble columns in the Greek quarter of Smyrna. They started a family within the year, and their daughter Eleftheria (‘Liberty’) was born around 1921. It seemed their life was set for a prosperous and bountiful future.

Miria’s grandparents, Aristides and Anastasia Kampaklis, had four sons: Nicholas, Yiannis (Jack), Omiros and Efthimios (Jim), and a daughter, Hermione (Mary – Miria’s mother). Aristides was a merchant who ran a tavern on the waterfront in Smyrna. He was an industrious man who also assisted the extended family on the land. His father owned flour mills and Aristides learned how to grind the wheat into flour and bake bread. He had a small boat and would regularly sail to the Greek Islands across the Aegean Sea to sell his produce.

Anastasia was an accomplished young woman, who had completed two years at high school before her marriage. She was a sought-after tutor for the local children, and she taught them to read and write in Greek. While Aristides was away, it is imagined she spent her days with her mother-in-law and friends, including Evdokia, in Vourla. Social life centred around the Greek Orthodox Church and Name Day celebrations. Family and friends would gather to share Smyrnean cuisine, and they would sing and dance to traditional Greek music. Greek spoon sweets, tou koutaliou, were always offered on arrival, followed by a small Turkish coffee. Smyrna has a long history as a cultural and trading centre, having thrived on its mix of races, religions and cultures. It was a prosperous port and merchant township, inhabited by Greeks, Armenians, Levantines, French, Americans, Turks, Christians, Jews and Muslims who coexisted in a respectful and tolerant manner.

On balmy evenings, couples and families would promenade along the picturesque waterfront with its impressive neoclassical architecture, conversing with others and enjoying a life of plenitude. Surrounding the city port was a rich, fertile land, which was farmed by our forebears, giving rise to citrus fruit, figs, grapes, olives, tobacco, wheat and silk.

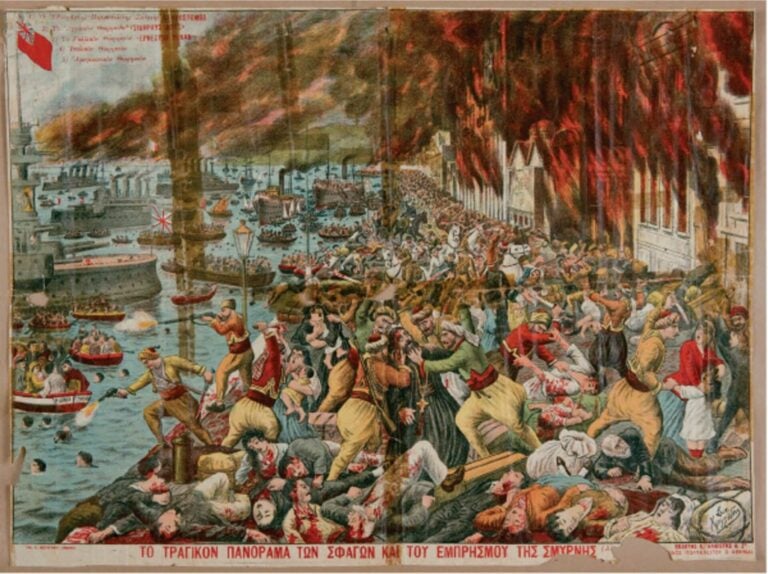

However, this idyll vanished all too soon after the sacking and burning of Smyrna in September 1922, where Christian Greeks and Armenians were endangered, persecuted and killed, culminating in a catastrophic wave of ethnic cleansing. In late August that year, Aristides was warned by a friend, a Turkish Government official who drank at his tavern, that trouble was brewing politically. He was emphatic that Aristides should take his family and leave without delay. Aristides collected his family from Vourla, put them in a small caique (sailing boat) at night, and set off to Samos Island where they hid in the mountains for thirty days until they were able to get a boat to the Greek mainland.

Bayliss was likewise warned by his close Turkish friends. Just prior to the burning of the city, he locked up his house and the wine shop, took Evdokia and the baby (along with their incense burner, gold watch, bangles and icons), buried the keys for when they could return, and fled by boat to Athens, in fear of their lives.

In Athens, our grandparents, as refugees from Asia Minor, were made to feel unwelcome, and local Greeks called them xeni (foreigners) even though they were Ionian Greeks. Bayliss and Evdokia’s losses were compounded by the death of little Elephtheria from pneumonia in a basement. Aristides was fortunate to be able to establish himself in a grain store business, when he was reunited with Bayliss at a kafenion (coffee shop). A compatriot convinced them that they should consider building a future in Australia, to kato kosmo (the Land Down Under), as it had many opportunities for migrants who were prepared to work hard, and had the advantages of being far away from the wars of Europe as well as being free of conscription.

Together in Athens, the Kampaklis and Xeros families made the courageous decision to immigrate as refugees to Australia. In August 1924, they boarded the Italian ship Carignano in Piraeus, Athens, bound for Melbourne. Their ship finally berthed in Melbourne at Station Pier. It was 7 November 1924 – Melbourne Cup Day – and the city was quiet. The families thought it was a religious holiday. The journey to Australia had taken three long months and conditions were severe. Evdokia was heavily pregnant during the journey, and seven year old Omiros had fallen ill with pneumonia.

After arrival at Station Pier, the families were met by a fellow compatriot, George Heliotis (Helos), who took them to a rental property at 30 Eastern Road in South Melbourne, a suburb where many Greek families had already settled. However, the sick Omiros was not able to accompany his parents, as he was quarantined immediately on arrival and admitted to the Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital at Yarra Bend Road, Fairfield, where he tragically died three days later.

In the 1920s there was little support for new migrants in Australia. There were no interpreters, English classes or government assistance. The Great Depression was looming and employment for migrants was scarce in the city, so Bayliss travelled up to Mildura to try and find work so that he would be able to earn a living to support his family. Mildura was chosen as it was a centre for the dried fruits industry, and there was a culture of employing immigrant workers. In addition, it had a similar climate to Smyrna, and there were grapes and citrus fruit that grew there with which Bayliss and his family were familiar from their homeland in Asia Minor.

Back in South Melbourne, Evdokia went into labour without her husband there to support her. Anastasia raised the alarm by running into the street and calling in broken English for help to get Evdokia to the hospital. Evdokia delivered her second baby, Nicholas, at the Royal Melbourne Hospital on 6 December 1924 – just four weeks after having disembarked in Melbourne. After the birth, Evdokia moved to Mildura to join her husband where he had found farming work in Mildura with WB Chaffey.

Within the year Bayliss and Evdokia were joined by Aristides and his family, as Aristides had found work in share farming in the area. Together they lived in the same small weatherboard house, in quite primitive conditions. Evdokia and Anastasia nurtured their children while they cooked, cleaned, embroidered and crocheted together. This companionship provided the support they all needed. Under the stars, our grandparents recalled the homeland by giving voice to the lamenting Rebetika – a type of Greek popular song accompanied by instruments such as violin and bouzouki.

Evdokia and Anastasia were both capable and resilient women who were forced to adapt to their often difficult circumstances and losses. There was no contraception, and it was common for women to have many pregnancies and also many perinatal losses. Evdokia went on to carry twelve further pregnancies, but in all only five of her babies survived to adulthood. They were Nicholas (Nick), Odyssea (Ulysses or John), George, Sophia’s mother Maria, and Eleptheria (Liberty or Libby).

Anastasia had eleven pregnancies, and only four of her children lived to adulthood. In 1925, within twelve months of arriving in Melbourne, Anastasia gave birth to a daughter, Eleni.

Unfortunately, Eleni died in infancy after an accident caused by caustic soda inhalation within the shared house in Mildura. The Kampaklis family returned to Melbourne after this tragedy, and sadly the families lost contact – although later in life Anastasia asked to be reunited with Evdokia. Many grandchildren and great-grandchildren have followed on both sides, and their grandchildren Miria and Sophia have come together to recount and tell the amazing stories of survival, of courage and the sometimes arduous experiences of travelling from their beloved Smyrna to Station Pier in Melbourne, to build for themselves and their children a future of possibility.

The story was initially published by Lella Cariddi and Multicultural Arts Victoria.