When Frenchmen arrived in the bend of the Mississippi River that would eventually be named New Orleans, they encountered a place that had been home to Native Americans for about 1,300 years. Prior to colonization, there were various American Indian settlements around the old city (referred to by English-speakers as the French Quarter) and surrounds. Tchoupitoulas Street shares an origin with the ‘village of the Chapitoulas’, or ‘river people’. The Chapitoulas were one of the small Indigenous groups that moved up and down the river according to trade routes and seasonal hunting in the 1600’s and early 1700’s. That bend in the river eventually gave New Orleans its alternate name – the Crescent City. Founded in 1718 and named for the Duke of Orleans, from the start La Nouvelle-Orléans was special.

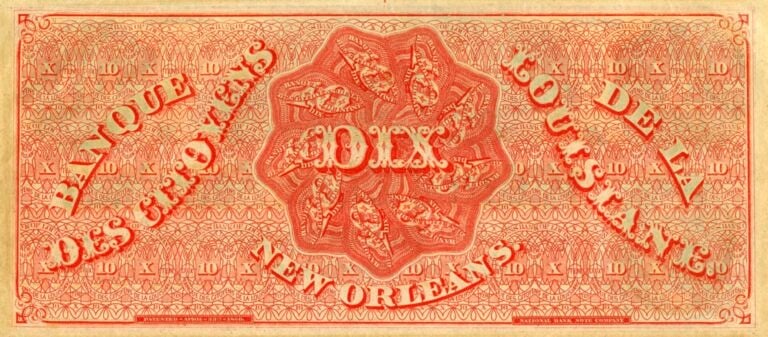

Named in honor of the King of France, Louis the 14th (the Sun King), the State of Louisiana – referred to colloquially as ‘Dixieland’ – came late to the United States. $10 notes issued before 1860 by the Citizens’ Bank of New Orleans and used largely by French-speaking residents were imprinted with dix (French for “ten”) on the reverse side—hence the land of Dixies, or Dixie Land, which applied to Louisiana and eventually the whole South. After long colonial rule by the French (punctuated by a short period as a Spanish possession), Louisiana was purchased from Napoleon Bonaparte by the 27 year old US Government in 1803 – known as the ‘Louisiana Purchase’. Napoleon sold France’s American territories for just $US15m (or approximately eighteen dollars per square mile) to finance his European military conquests at the time. An influx of Anglo-Americans ensued joining what was already a gumbo of European, African, Latin American, Caribbean, and Indigenous peoples. Throughout the 19th century, New Orleans was the largest port in the Southern United States and the second largest nationally after New York.

Key to the multicultural mix, the African American community has played an intrinsic role in creating New Orleans, structurally, economically, and culturally. Italians also made an important contribution in the development of New Orleans unique music genres – from jazz to rhythm and blues (R&B). Only New York City has a higher population of Sicilian-Americans than New Orleans. In the nineteenth century, there was a regular ferry service across the Gulf of Mexico from Havana and up the Mississippi Delta to New Orleans; a conduit for Latin American influences. More recently large waves of Vietnamese arrived in New Orleans beginning around 1975 after the Fall of Saigon; drawn by the similar climate to that of Vietnam and a common historical experience of colonization by France.

The Greek Orthodox Holy Trinity Cathedral on ‘Bayou Saint John’ near Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans is the oldest in the Americas and home to the first Greek American community in the USA. They have an annual Spring festival called ‘Greece on the Bayou’. We had the opportunity to attend in 2012 – it was huge. The Greek population in New Orleans began to grow from the 18th Century because of the port. A new wave of immigrants in the 1800s brought their customs and their religion. Another wave of immigration from Greece occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral became the center of what is known as “Greek Town” in New Orleans.

An integral part of that culturally diverse gumbo were the Créoles. It took me a while to get a handle on this important cohort of the Louisiana population. I think I am right in saying that it is a term whose meaning changed over time. Originally it referred to American-born French people. But over time it came to refer to Americans of mixed French and African heritage. An earlier layer of French influence came with the Cajuns, displaced French-speakers from Canada, who were re-settled in the Louisiana bayous and gave the world Zydeco music. On one visit, my partner Julie and I went to a popular Cajun Sunday afternoon dance at Tipatina’s on the corner of Tchoupitoulas Street and Napoleon Avenue (pictured); certainly the music lyrics were sung in French but, blow-me-down, many of the older community members were still speaking French!

One legacy of this atypical history for an American state is that the Louisiana legal system remains based on the Napoleonic Code to this day. This idiosyncrasy was significant in the conception of America’s crowning cultural triumph – jazz. Unlike the rest of the country, under the Napoleonic Code in pre-Civil War days, Sundays were a free day for African American slaves. On Sundays in New Orleans, they typically congregated in Congo Square to sing, dance, socialise and conduct business. The square – notionally the Ground Zero of Jazz – is now a corner of Louis Armstrong Park in Treme. Bordering the French Quarter, the Treme district became the first neighbourhood of free African Americans in the US and remains the spiritual home of jazz. Today it is the centre of New Orleans’ African American and Créole culture, especially the modern brass band tradition. It is home to the New Orleans African American Museum.

New Orleans’ greatest contemporary young musician is 36-year-old Troy Andrews, aka Trombone Shorty. Recently he was a headline performer at the 2022 Newport Jazz Festival earlier this year. Coming out of jazz and brass bands, he has taken the city’s jazz and R&B traditions into a hard-edged rock band format. Troy now takes his rich musical heritage to a new generation of young audiences around the world with whom he is both popular and respected for his musicianship.

Troy and his brother James performed their grandfather Jessie Hill’s 1960 R&B hit “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” at the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport in Episode 7 of the first HBO Treme television series season which premiered in 2010. Older readers will best remember that tune being performed by Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs at the Sunbury Festival in 1972. A little-known fact is that Johnny O’Keefe, who also performed at Sunbury, reached # 1 on the 1960 New Orleans hit parade with his B-side tune “It’s Too Late”. We came across the production crew filming ‘Treme’ around town several times in 2012 and 2013 and, on one occasion on Treme Street, chatted with members of the crew. The series continued for four seasons through to the end of 2013.

After lunch with her at Li’l Dizzy’s Café in Treme, New Orleans traditional jazz radio program presenter Sally Young introduced Julie and me to Troy on our most recent visit in October 2016. WWOZ 90.7FM is the New Orleans jazz and heritage community radio station. It is located between the French Market and the Mississippi River in the French Quarter. You can watch ships sailing up and down the Mississippi from the studio window.

WWOZ is the worldwide voice, archive, and flag-bearer of New Orleans culture and musical heritage. Sally is a stalwart of the New Orleans music scene. She has volunteered at JazzFest and similar events since she was a teenager. From age 17 when she first got her Driver’s License she was driver for another blues legend – Lightnin’ Hopkins – whenever he came to town. She signed us up as volunteers for the 2016 Crescent City Blues & BBQ Festival – so we got to hang-out in the Green Room! Sally has a traditional jazz program on WWOZ every Thursday 9:00 am-11:00 am local time; you can listen in live on-line in the wee small hours of Friday mornings (our time in Eastern Australia), or catch recordings of recent shows off the website www.wwoz.org.

Julie and I first met Sally at a concert at the Mahalia Jackson Performing Arts Centre in Armstrong Park in 2012 and became good friends over two subsequent visits; most recently in October 2016 where we met up a couple of times at the radio station. On that last occasion Sally was interviewing jazz musician and bandleader – Lars Edegran – on air. They were playing tunes from Lars’ newly released “Triolian String Band” CD, which to my ear had a whimsical familiar ambiance. Some tracks featured vocals by the much-loved late Uncle Lionel Batiste, who is better known for performing on bass drum with the Treme Brass Band. Towards the end of the program Sally invited me to say a few words on air – so I took the opportunity to tell New Orleans listeners about Melbourne community radio station, PBS 106.7FM, which has a similar broadcasting philosophy. Photo: Julie and Sally in Mid-City New Orleans.

After the show, Sally took us to Lars’ record store, “Jazzology”, on the other side of the French Market. It’s just behind the Palm Court Jazz Café which is on Decatur Street and where Lars is a regular performer. I was particularly looking for any recordings by clarinetist George Lewis. The late Nick Polites OAM, who played with Melbourne’s Louisiana Shakers, had told me he modelled his playing style on George Lewis; that’s why I was keen to find his recordings at Lars’ record store. Lars recommended a two-disc set “The Best of George Lewis 1943-1964”. Turns out that Nick and Lars were old friends and musical collaborators, so I put them back in touch with each other and they corresponded following our chance meeting at the WWOZ studio! So I also purchased Lars’ “Triolian String Band” CD to give Nick when we returned to Melbourne.

Nick had made several pilgrimages to New Orleans when he was younger; and he did meet and befriend George Lewis. They had previously met briefly in London where Nick had been performing. On his first visit to New Orleans in 1963, Nick played duets (2 clarinets) with George Lewis. That year George Lewis took a band to Japan. George’s regular group did not wish to travel, so he took other musicians and Nick was asked to take his place with the regular group who continued to perform in New Orleans during George’s absence.

I told Lars and Sally that in 1954 Louis Armstrong’s band visited Australia for the first time. Nick hosted a party for the band at his parent’s house in Melbourne, and during the party Louis’ band set-up and performed. Nick was invited to play clarinet alongside of Louis Armstrong and his famous All Stars band. That’s my one degree of separation from Sachmo! On an earlier visit to New York in 2013, Julie and I were able to visit Louis’ home – now a museum – at 107th Street in Corona, Queens where he lived from 1943 until he passed in 1971. And we attended a Louis Armstrong tribute concert at the Brooklyn Academy of Music – anchored by a fellow musician from New Orleans, the late Mac Rebennack, aka Dr. John the Night Tripper. That concert featured James Andrews (Trombone Shorty’s older brother), and Kermit Ruffins who we would later meet and chat with in New Orleans at his Speakeasy cafe in Basin Street; and see perform at music venues along Frenchman Street.

We lost Nick Polites at the age of 94 earlier this year, in January 2022. Up until he turned 90 he was performing a regular Sunday afternoon gig with his band – the Louisiana Shakers – at the Clyde Hotel in Carlton. In 1951 Nick had joined and commenced recording with Frank Johnson’s Fabulous Dixielanders. Would you believe that six months earlier, before Nick joined them, the Dixielanders were the wedding band at my parents’ wedding! That was on 1 October 1950. The band even learnt some Greek folk tunes from my grandmother’s 78’s collection to play at the wedding! My parents told me that is how the tune “Varka Yiallo” entered the Melbourne jazz scene repertoire. I have a Dixielanders recording of it with Nick, Frank and Smacka Fitzgibbon on vocals – all singing in Greek – look for it on YouTube!

You can find the obituary I wrote for Nick Polites published in Neos Kosmos on-line. Though Nick’s funeral service was secular, it was conducted in a traditional New Orleans fashion. A brass band led the casket and procession of mourners in to the chapel and eulogies were punctuated with live jazz music. The New Orleans style brass band – made up of Nick’s friends and musical collaborators – then led the procession away from the service.

Nick was Melbourne’s very own keeper of the flame for the 1940s revival of New Orleans’ “Dixieland” music which harked back to the original Dixieland jazz style. His music lives on in the many recordings he made over seven decades.

For us in Melbourne, Nick Polites made a huge contribution to ensuring New Orleans remains a special city that lives in our imagination, and an influence on much more of the popular music we all listen to than we can ever imagine.