Humanity has been trying to put its finger on a commonly accepted definition of art for millennia. Is it the aesthetically pleasing juxtaposition of textures, shapes and colours? Is it the play on light? Is it the spark in imagination or the build up of emotion when its experienced with one or more of the senses?

What everyone seems to be agreeing on is that art is supposed to make you feel something, to make you think, to make you question. Art takes you on a journey and changes you. The most impactful works of art have been so well-timed in their respective eras, that they are rendered timeless.

In many ways, multidisciplinary artist Konstantin Dimopoulos, tries to impact his surroundings by reinterpreting them and at the same time leaving a lot to the imagination. His practice brings attention to the present to raise awareness for the future, incorporating sculpture, installation, performance painting, printing and drawing in the creation of monumental imagery, social and environmental interventions and conceptual proposals that argue the potential of “art” as a means of social engagement and change.

“As an artist, I would love to think that art was the light of the world…,” he tells me. “It sounds good, but in reality, we as artists are merely the ‘Cracks’ that allow the light to come through, that allows in this instance the science, that you bring the facts -not the alternate facts, not the lies – but the real facts about the ecocide and what’s happening to forests and in a small way try to make this to become visible.”

The medium he uses often depends on the initial, the intention. As a social artist, he creates works that relate to a variety of issues he feels need to be addressed.

Dimopoulos taps into homelessness in his ‘Purple Rain’ installation, domestic violence in ‘Paradise lost’, and into the human impact on the planet- called ‘Level 4 /works from a savage garden’.

“For ‘Level 4’, I used gorse, a plant which I brought into the museum walls, that grows like a weed in New Zealand and is very hard to destroy. And related the viral nature of the plant to our own viral status,” he explains.

Dimopoulos quotes David Attenborough, who described us as “the worst virus, plague on the planet”.

EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED

Born in Port Said, Egypt to Greek parents he grew up at the mouth of the Suez Canal until the age of eight, when the family moved to Wellington, New Zealand. Early on, his paintings and prints explored the human condition through the prism of his experiences. From installations and collections of works exhibited in galleries and museums for decades, he chose to step into the brutalism of public domain.

“Public art, it is not an easy arena to work in,” he stresses, before describing it as the “Hurt Locker of the art department” because it has the tendency to explode from the varied opinions of the public.

“Ultimately, I believe that public art is not so much about understanding what the individual works mean, but more that the society in which it resides is one that is open to creation, open to wonderment, open to mystery. Public sculpture and architecture are the face of a community; a society that is strong and certain about its own identity, willing to embrace diversity. And failure? I have seen virus; the blue trees and purple rain evolve.”

Dimopoulos, speaks in metaphors, riddles, and pauses. He weaves them all into his spoken narrative, almost as an extension of his physical artworks.

“No man is an Island, we are all part of the continent part of the main…” he says. “The forests have become a metaphor for our continual disregard of the importance of the natural world and to the destruction of our mental and physical health. By destroying the forests, we have opened up the Pandora’s box of viruses.”

Covid has changed both the social and environmental landscape that we once took for granted, he highlights, showing how interconnected we are as a species to each other and to our environment.

“Breathing became an exercise in survival. My art practice therefore has not so much developed, but more it has had time to review itself. I have come to appreciate, is the very act of breathing and how trees are so important to that process. Death became much more a part of our everyday lives like never before, where the number of dead, was read out on the news every morning, No names just numbers like a trumpet call to the living. Ten, fifteen, twenty… we we’re fixated by numbers.”

INSPIRATION AS A RIPPLE EFFECT

For Dimopoulos, ideas for artworks often come from creating or being in certain environments. For instance, the ‘Blue Trees’ was created after moving from New Zealand to Melbourne. Melbourne has one of the largest urban forests in the world whereas Wellington, where Dimopoulos grew up has few trees. Seeing the urban forest began the process for his installation. While recreating it in Seattle, there were hundreds of homeless people living outside, near the trees, spread out like trees.

“My time spent with them and them (the homeless) helping me with the blue trees led to the creation of ‘The Purple Rain’,” he explains. “While living in New York, the amount of rubbish in the streets… I began working on creating ‘Black Pyramid’, which created black rubbish bags of rubbish in a pyramid shape.

“One idea often leads to another but the critical part is living in a particular city or environment opens the way to create new works. In Wellington the wind was a critical part so I created wind sculptures. ‘Pacific Grass’ is a moving sculpture outside Wellington airport.”

The art, for Dimopoulos, is to bring forward ideas or issues that interest him and transmit them in the hope that others will process them in a new perspective.

“These concepts are not in themselves methods of dealing or fixing deforestation or homelessness,” he stresses. I hope that by bringing them to the forefront it will make people review their own way of looking at these and perhaps through empathy, I can move them to help.”

Be it a virus, deforestation, climate change, homelessness or war, it is in the darkest of times historically that art finds a way to break through the darkness and bring light and colour to the world.

“In a kind of bizarre way, I started to look at how to use colour to make these disappearing forests visible and bring their voice into the urban environment. Colour moves us to a variety of emotions. It is a great antidote to greyness and inertia and dull acceptance. Colour is an incredible powerful stimulant. The fact that blue is a colour that is not naturally identified with trees suggests to people that something unusual, something out of the ordinary has happened. For me, blue suggests sacredness, breathlessness and mystery.”

Dimopoulos argues that we must stop talking as though only masterpieces matter. That art is needed in all its diverse faces, just like nature is. Art has always been an integral part of his genetic makeup, a way with which he discovers himself, a vehicle that tries to bring into view the invisible – whether its Michelangelo making God visible in the Sistine Chapel, Picasso showing us the bombing and deaths in Guernica or Goya and the dark prints of war, superstition, and personal violence that have found resonance time and time again.

The best quote that reflects how Dimopoulos feels that art helps to break through limitations is: “Few will have the greatness to bend history itself, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events. Each time we stand up for an ideal, or act to improve the lot of others, or strike out against injustice, we send forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centres of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls.”

He saw the ripple of growing and moving from cities, to communities, to schools, and individuals expand from his “small contribution”.

RISING FROM THE ASHES

“It’s been an exciting time in terms of art for me at the moment,” he tells Neos Kosmos as he parallels his journey to the one of archetype of the Phoenix.

“I have been invited to create the ‘Blue Trees’ as part of the environmental call to action at Bibliotheca degli Alberi, Milan, Italy. The cultural program of 2023 will be based on a simple but powerful theme: the colour.”

After three years that for the most part felt like a plateau, Dimopoulos will then return to the US to create his famous Blue Trees in Memphis, followed by a residency at the Lawton Gallery, University of Wisconsin. Currently, he is completing a major public art sculptural installation for The Howard Hughes Corporation in Houston Texas called ‘Rising Knoll’.

“Due to a lot of my public art was postponed during the pandemic, I started to look at other mediums like digital art and augmented reality (AR). One of the concepts was a commission from the Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx titled ‘Eden must be Destroyed’.

“There is a sense here that we have broken our covenant with Nature – and activated ‘our fall’ and subsequently our expulsion from the Garden of Eden,” Dimopoulos explains.

In the work the figures walk out from the frame and into the foreground.

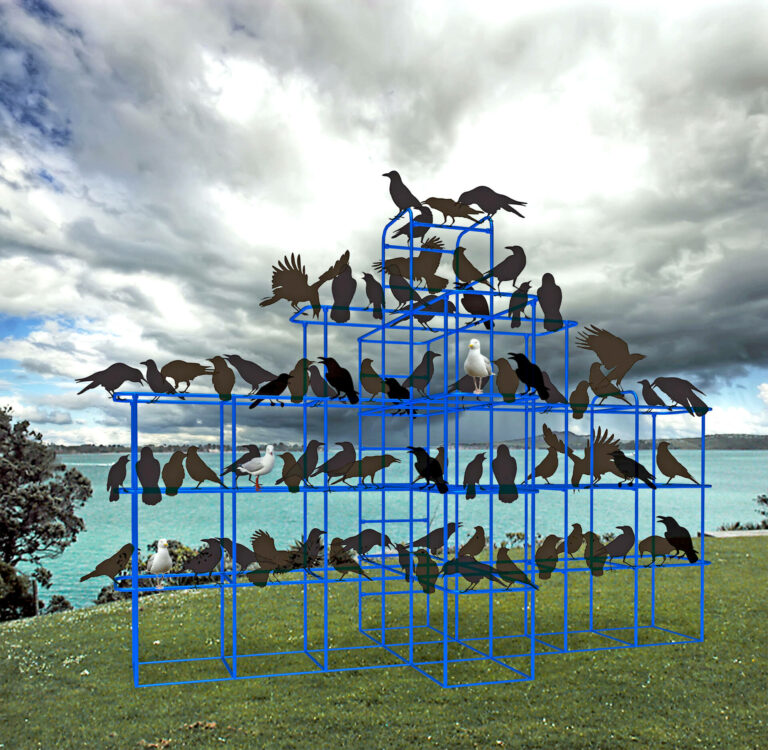

Another large sculptural work of his ‘Beyond Good and Evil’, will grace the Prancing Horse Estate, in Mornington Peninsula. A project realised with the support of Tony and Cathie Hancy -two major philanthropists in the arts- and Heide Museum of Modern Art. With its reference to Hitchcock’s psychological thriller ‘The Birds’, Dimopoulos’ Beyond Good and Evil’ explores the narrative of people’s memory and anxiety.

“Our remembering of past images often leaves marks in our psyche. These marks are explored here through a sculpture that brings out a collective memory that has been exploited for centuries through film and fiction. ‘Beyond Good and Evil’ explores how these marks create emotions that become a part of our reality.”

The prolific artist is also preparing a new series of neon works, prints and paintings, to be shown at the Metro Gallery, in Melbourne, while also submitting a painting for the Archibald Prize. Yet, his return from 2020’s enforced hiatus does not stop there.

Dimopoulos continues to pursue the return of the Parthenon Marbles hoping to ignite not only the Greek Community’s but also the global community’s support.

“The global work is called ‘Black Parthenon’ which relates to his 2009 ‘Light Work’ created in Melbourne. We are going to look at shrouding major landmarks around the world using black material, that reflects the lamentation around the marbles, and that will lend support by major cities to the return of the marbles that were stolen from Athens.”

“These would include Chicago and Melbourne who are the third and fourth largest Greek cities outside of Greece. There has been great support for the return from around the world including Stephen Fry, Christopher Hitchens and Amal and George Clooney. If nature doesn’t throw another spun in the works, I will keep pushing through with all these projects.”