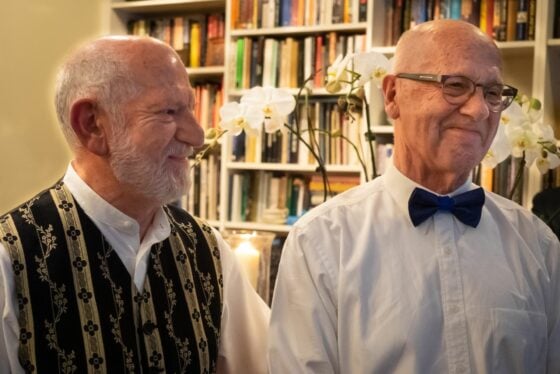

Lee Christofis was awarded an AM for his contribution to the arts. He was recognised for his services as one of Australia’s principal dance critics. He has worked for ABC Arts, The Australian, and many other journals since 1981. Lee Christofis and I met in 2000, when we conspired on various projects that sought to expand cultural diversity in audiences for the arts and have remained friends since.

A 12-year-old Lee Christofis wagged school to attend ballet matinees “of the Borovansky Ballet, to see Giselle”.

“I hated school at times. I had asthma as a child, so I’d pretend to throw an asthma attack, and say, ‘I can’t breathe… I need to go home.'”

“I’d pinch money from my father’s wallet and take myself off to the ballet,” often the only kid in a theatre full of “older ladies.”

“I was overwhelmed by the AM,” he said, giving a last stir to the brewing Greek coffee.

“It took him completely by surprise,” added Neil Gill, his spouse.

READ MORE: 13 Greek Australians recognised in Queen’s Birthday Honours List

The house love built

Lee and Neil’s elegant Tuscan blue Fitzroy house hosts a grand piano in the library and sitting room that faces a beautiful courtyard.

The house’s walls have soaked in years of dinner parties, lively discussions, and abundant love.

Their garden, where we go to talk, is a verdant sanctuary to local birds.

“With the trees going from all the development around here, the birds all come here now,” Neil said.

“He feeds them, you know,” Lee said, smiling mischievously.

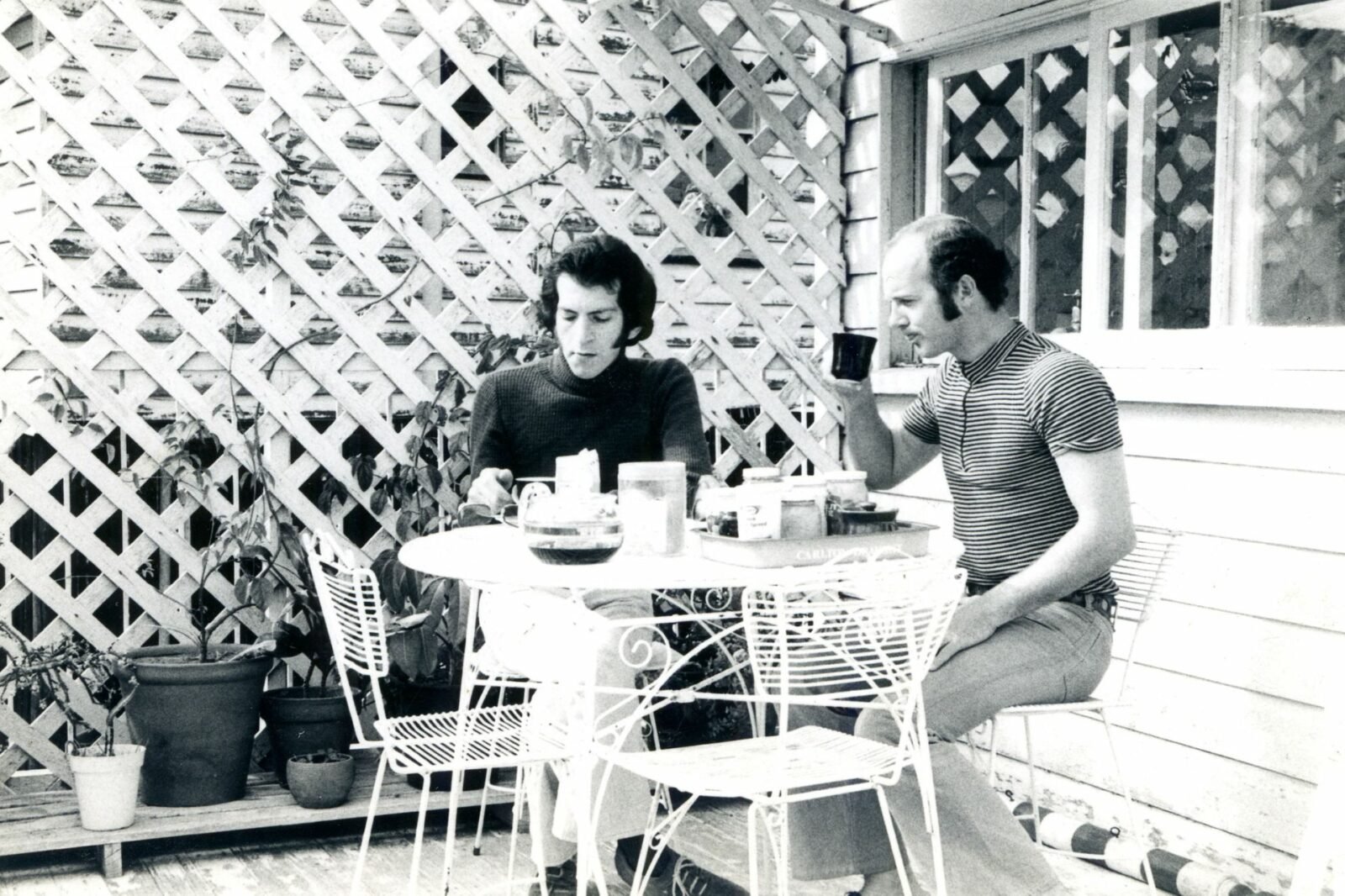

Neil Gill and Lee met in Brisbane in the early 1970s and fell in love.

Lee fell in love with dance at the age of four, “I always wanted to be a ballet dancer.”

At 14, when he began, it was “too late.”

He attended university for a year but failed.

“I was doing dance classes all the time.”

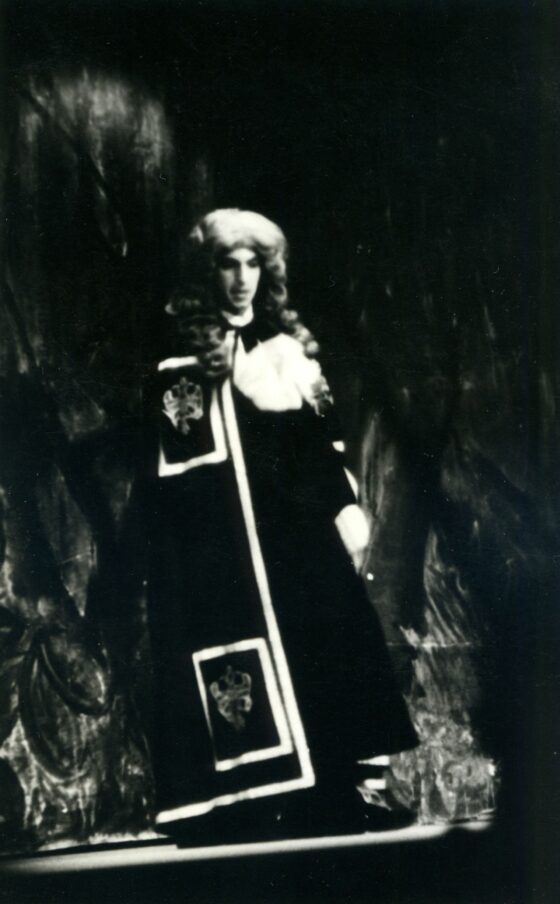

Lee danced in three seasons between 1967 and 1969 in the Queensland Ballet but his ballet career ended at the age of 21. His last performance was in “Oedipus Rex” with music by Stravinsky. He danced in the chorus and later played Tiresias, the blind old prophet who revealed to Oedipus his crime against nature.

“I was on buskins, like the Ancient Greeks used, I wore a long hessian gown and a long white wig down over my shoulders and carried a huge staff.

“I walked across the stage, very, very, slowly with a little boy holding my hand. I had to take two minutes to raise my hand and touch Oedipus on the head, revealing his messy parenting.”

The Greek tragedy was the end of Lee’s career as a dancer.

“We had no money, the company’s first grant from the Queensland Government was $3,500.”

Lee rejected an opportunity to tour in “Coppélia” and resigned.

“I had asthma and was 57kgs, a skinny thing, I had no physical capacity to work full time as a dancer, so I stopped. I sank into depression for two years, although I had a good day job with the GPO.”

He began to frequent galleries, and soon he met “painters, designers, sculptors and jewelers” and was invited to openings and parties.

It was “an entirely new scene”.

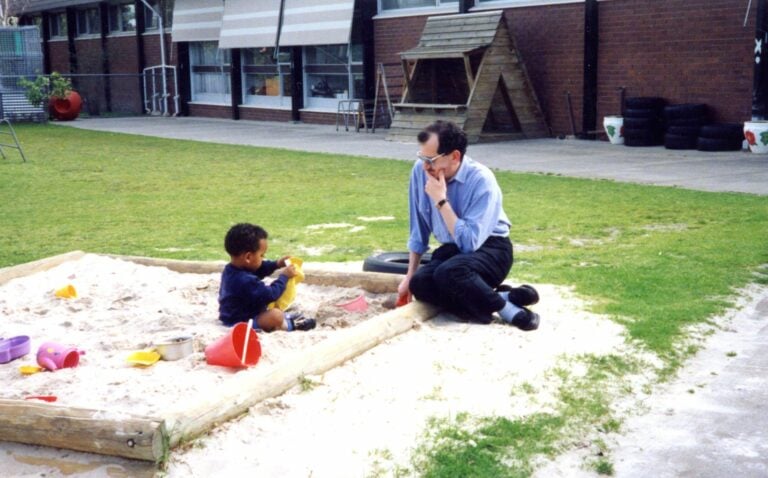

Lee also studied kindergarten teaching and became a pioneering male graduate.

New life in Melbourne

Neil Gill, a former Anglican priest, had joined the ABC as the Producer of Religious Programs. In 1981, Neil took on the role of Supervisor of ABC Religious in Melbourne. They moved from Brisbane to start a new life in Melbourne and Lee worked in childcare.

Bob Hailstone, General Manager for ABC Queensland, visited them in Brisbane at a dinner party and spoke of a new arts show.

“Bob said, ‘I have a visual arts reviewer, a theatre and music reviewer, but I am missing a dance critic.’ The next day, Bob rang and said, ‘I found a dance critic – it’s you.'”

A good critic does not tear down “artists as sport,” says Lee.

Lee recalls how at a performance after party, a young ballet ancer approached him and said, “I like your reviews, when I read them. I feel as though you are writing to us.”

Lee thanked him and said, “I like your dancing too.”

That performer’s words summarised Lee’s values as a critic.

“I strive to put a performance in context, if I am writing about the Australian Ballet, I will write in a different way than say a review of work by new graduates.”

READ MORE: Max Richter’s Sleep, a filmed antidote to modern life with music to dream by

Stratis Christofides (seated) with a friend, as a young man in Egypt.

Statis and Evangelia Christofis in their Brisbane home

Lee Christofis and Neil Gill in Brisbane having breakfast in 1972

Migration’s complex threads

Stratis Christofides, Lee’s father, was born in Cyprus and taken to Egypt at the age of eleven “by a relative, ostensibly to be educated, but put him to work in a bakery.”

“Imagine! Taken away from your parents and dumped in a bakery in Ismailia.

“He was a well-educated, albeit self-taught man.

“A widow who owned a hotel in Port Said was visiting Ismailia, she saw something in him and said, ‘You look like a smart boy, come with me to work in my hotel’, so she took him to work in her hotel in Port Said.

“In the middle of World War I, a widower who lived in the hotel, told my father to get out of Egypt.

“He said, ‘Egypt is finished, Europe is falling apart, get out.'”

Lee’s father arrived in Australia in 1916, and he “built cafe after cafe and made good money”. Evangelia Mousouris, Lee’s mother, was born in Egypt, to parents from the island of Kasos. Her relatives worked for the Suez Canal Company.

His father returned to Egypt in 1933 to marry Evangelia, then settled in Brisbane. They had two children when WWII erupted and did not return to the Middle East.

Lee’s parents were leaders in Brisbane’s Greek Community, his father “built Brisbane’s Greek Orthodox Church of St George.”

They developed community theatre, music performances, soirees and were central to the Hellenic community’s life.

In the 1950s they assisted Greeks expelled from Egypt after the fall or British rule, and later. Cypriots fleeing the war of independence against Britain.

Lee’s passion for social justice, and his love of the arts stem from his parents.

Lee’s father’s confectionary shop was next to Her Majesty’s Theatre in the Brisbane CBD.

“My father would leave the shop and go to the opera; he took my older sister to many Italian operas; my mother went once and laughed all the way through it.”

READ MORE: Cotton roads: Greek entrepreneurs in Ottoman Egypt

Coming out as gay was a “very private affair” for Lee. It was 1968 and he was twenty.

“I came out first to my big sister. We both wept, then she said, ‘Ok, so you’re gay.’

“My parents knew, but we never talked about it; someone asked me once, ‘Why don’t you come out to them, everyone is doing it?’

“And I said, ‘I would not insult their intelligence.'”

“My parents were traditional, in the cultural sense, but urbane and very tolerant for their time.”

As the light fades

Our conversation weaves on to dusk. We talk about art, cultural policy, families, migration, and of course, politics.

We reminisce about travel in pre-pandemic times, Cyprus, Italy, France, Croatia, US, and Greece, until the thin sun that washed over us on this winter’s day fades.