The month of April is anticipated to become a historic moment for Greek Australian relations when the nine Evzones, soldiers of the Greek Presidential Guard, arrive in Adelaide and Sydney to participate in ceremonies marking Anzac Day and the 76th anniversary of the Battle of Crete.

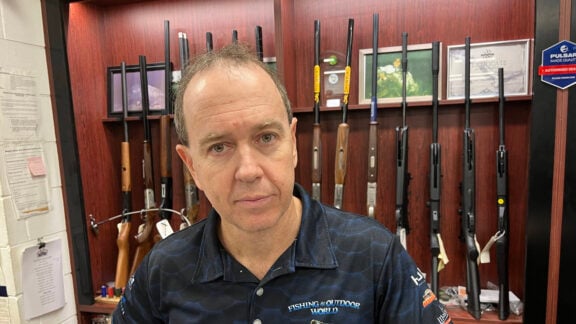

“The defence of Greece by the Anzacs and other Commonwealth forces in the Second World War is recognised and appreciated,” says the trustee of the Foundation for Hellenic Studies, Harry Patsouris, in an interview with Neos Kosmos. Mr Patsouris, in collaboration with Arthur Balayannis of the Hellenic Club Sydney, has coordinated the visit of the Evzones, who to this day remain the highest level of military guard in Greece.

“After obtaining special permission of attendance by the Greek government, the nine Evzones and their two lieutenants will visit the two cities in order to celebrate the role of the soldiers of Greece and Crete, often known as the ‘forgotten Anzacs,” explains Mr Patsouris.

As part of their visit, the Evzones will also take part in the Easter celebrations and will attend the War Memorial on North Terrace (Adelaide) to pay their respects to the Anzacs who fought in Greece and Crete.

Over 100 years ago, in the First World War, there was a link formed that connects the two countries, Australia and Greece, forever in time.

Despite the fact that World War I did not directly threaten the territorial integrity of Australia, the then government decided, as a member of the British Commonwealth and due to constitutional obligation towards Great Britain, to take part in the war. At Gallipoli would be the first time the newly-formed Australian Imperial force, known as the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, would take part in armed conflict.

Throughout this war, more than 300 Australian nurses, who were all volunteers for this great cause, served on the island in over 10 hospitals. When Australian troops finally retreated from Gallipoli in December 1915, they returned to Lemnos to find solace and rest. To this day, Lemnos is the site of two Commonwealth war graves, where many Australians are buried. The people of Lemnos welcomed the Australians as allies and friends, allowing access to their land and resources for as long as it was needed.

Though the Gallipoli campaign failed to achieve its military objectives of capturing Constantinople and knocking the Ottoman Empire out of the war, the actions of the Australian and New Zealand troops during the campaign bequeathed an intangible but powerful legacy.

BATTLE OF CRETE ‘A GREAT RISK IN A GOOD CAUSE’

In March 1941, Robert Menzies, prime minister of Australia, with the concurrence of his Cabinet, agreed to the sending of Australian troops to Greece. Both Menzies and the Australian commander in the Middle East, Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Blamey, felt that the operation was risky and might end in disaster but, like the British prime minister, Sir Winston Churchill, felt that Greece should be supported against German aggression and that the defence of Greece was a ‘great risk in a good cause’.

In Greece, Australians joined with a New Zealand and British force to defend the country against a threatened German invasion.

On 6 April 1941 the Germans began their invasion of Greece. Despite their efforts, the Allied force, together with the Greek units, were unable to halt the rapid German advance down central Greece towards Athens and, after a month of intensive fighting, the Allied force was evacuated from the Greek mainland on British and Australian warships and British transports.

About 39 per cent of the Australian troops in Greece were either killed, wounded or became prisoners of war, while more than 450,000 Greeks died during the next four years of German occupation, nearly 25,000 of them executed for assisting the Allies.

“According to historical data, 8,900 ANZAC prisoners of war were captured in Greece and 646 ANZACs are still buried or memorialised in Greece, 50 per cent of which are memorialised at the Athens Memorial, as their bodies were not recovered,” says Mr Patsouris who also reveals that it is estimated that there are tens of thousands of people in Australia today who are connected to the Battle of Crete, whether as descendants of Anzacs who fought, or Australians of Greek heritage whose families were affected by the event.

Most Australians that fell during the battle in Crete are buried in the British and Commonwealth War Cemetery at Suda Bay, on the northern coast of Crete, which over the years has received visits from thousands of Australians. The memorial that stands in honour of the Australians is called Stavromeni.

Although the detailed program of the events is yet to be released, the visit of the presidential guards, scheduled from 12 to 23 April in Adelaide and from 23 April to 2 May in Sydney, has been received with great enthusiasm by the members of the Greek and Australian community.