To call Christopher King a “sonic archaeologist” would be both appropriate and an understatement. The Grammy-winning producer (for his compilation of blues legend Charlie Patton recordings) has been stated as an influence on the likes of Nick Cave and Johnny Cash, and his 2007 three-CD compilation ‘People Take Warning! Murder Ballads and Disaster Songs 1913–1938’ featured liner notes written by Tom Waits. An avid collector of old 78rpm records, he has been in the business of archiving, remastering and reissuing music for quite some time, building an impressive body of work and gaining a reputation as a leading authority of the music of the past, someone who preserves sounds that might otherwise be lost forever.

This music is not merely for entertainment, like the vast majority of popular forms that exist now. Ultimately, it is a tool for survival, and we all need such tools

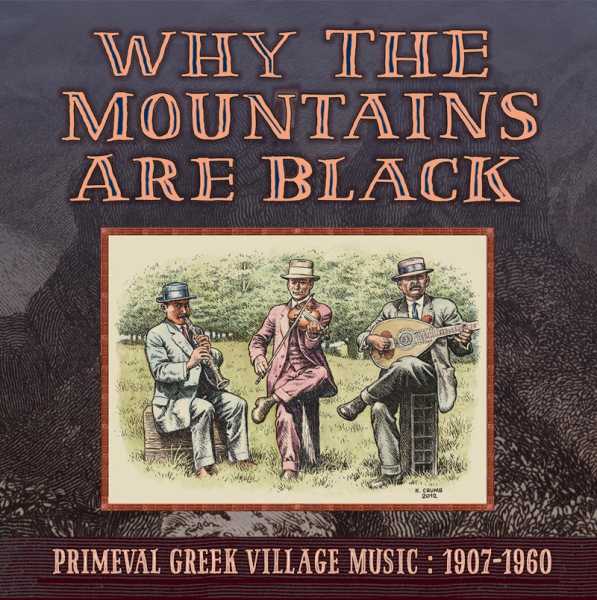

Still, it came as a surprise that King managed to persuade a label associated with a grittier American sound – rocker Jack White’s Third Man Records – to issue a compilation of Greek music. And not just any kind. Bearing the ominous title ‘Why the Mountains are Black’ – and with a cover drawn by the legendary underground comics artist Robert Crumb – the two-cd album features 28 recordings of ‘Primeval Greek Village Music’ made between 1907 and 1960. Even those familiar with traditional Greek music – the ‘demotica’ folk songs and dances of the rural areas – would find the recordings that Chris King selected to be really fascinating, but for the western listener, these exotic sounds should prove to be a gate to a different era and culture.

This is not the first collection of demotic music that Chris King has curated. He has published a few albums of Epirus music and has become an ‘honorary’ Epirot, spending time in the village community of Vitsa. On top of that, he is currently writing a book on the music of Epirus (to be published by W.W. Norton & Co. in New York). But it is this latest compilation that has attracted a wider interest in Greek traditional music, for people who discover that there is more to it than the bouzouki sound and the Zorba stereotype.

These are recordings made in Athens and New York, mostly during the first decades of the 20th century, showcasing music that was part of the social fabric of the rural areas it emerged from. In the liner notes – which make for a fascinating read – Chris King describes the ritualistic function of this music, connecting the sounds to the society of that era.

![]()

Speaking with Neos Kosmos, the producer discusses his own obsession with Greek music and the concept behind this album.

How did ‘Why the Mountains are Black’ come to be?

This collection has been in my mind for around six years. It is part of a serialisation: a series of several collections that address deeply philosophical themes through the lens of primarily Greek demotic music, the music of Epirus, of Crete, and of Asia Minor. The philosophical theme in this collection is the problem of evil (or the bad) and death and how the Greeks have addressed this problem in the past through their music. I became rather fixated on Greek demotic music, especially the music of Epirus, when I found, ‘junked’, a small stack of 78 rpm discs from Epirus and Southern Albania on the Asian side of Istanbul during a trip. This collection – like the serialisation – connects with my previous work in that I do not simply like to present old music in a pedantic or didactic manner, but rather I would like to be able to tell a personal story with this old music. It makes it more meaningful that way. I am invested in the music and the culture in that manner. You know, history (and music) can be told from different perspectives: the viewpoint of the victor or the vanquished or from the point of view of a field-mouse or a time-traveller. In this case, I like to tell the stories from a philosophical perspective.

How did it get to become part of the Third Man Records catalogue, which is not a label normally associated with this kind of music?

I was approached by Ben Blackwell of Third Man Records when he had heard that I was looking for a ‘home’ for my collections, which are admittedly idiosyncratic, personal and difficult, and this translated into a shrinking world of labels willing to issue them. They are not ‘money-makers’ and I also insist upon having artistic and editorial freedom to bring them into existence the way that I conceive them. This also narrows the number of labels that may want to issue such a collection. With Third Man Records and Ben Blackwell and Jack White, aesthetics and vision are more important than profits. They are motivated by deeper beliefs, things that provoke thought and conversation, such as this collection. What you see and hear before you was precisely the collection as I envisioned it along with the help of my designer, Susan Archie. When I presented it to Ben Blackwell and Third Man Records, he very quickly became absorbed with the music and the presentation and agreed to issue it.

How did you get Robert Crumb to draw the cover?

Robert is a friend of mine. We both love these old recordings. Gosh, he may even love them more than me … I’m not sure. But I trade him copies of these old 78s in exchange for the artwork that I use on the collections.

What sparked your own interest in old records from Greece?

My own interest began with old 78s from Greece when I found this small stack of Epirotic discs in Istanbul. Then I became obsessed not only with acquiring every Epirotic 78 I could find but also with acquiring the most moving, the most representative examples of demotica from Thrace/Macedonia, Crete, the islands, Thessaloniki, Thessaly, Peloponnese and Asia Minor. When all of these musics are gathered together, the context of say, a musician from Epirus becomes much more understandable.

My first reaction upon hearing my first Greek demotic disc, a skaros by Kitsos Harisiadis from Epirus, was that I could hear something behind the music, something intentional, something therapeutic, something familiar yet mysterious. It really drew me in, made me want to understand the structure and mechanisms both within the music and behind it, what cultural and historical aspects helped create this music and the need for this music. The question, ‘what is the purpose of this music?’ has now become something of a lifelong, all-consuming obsession. Each time I get a new disc of Greek music, it is as if a new chapter has been opened up in this eternal quest. I’m constantly seeking to understand how this music functioned among the rural-dwelling Greeks and how these ‘functional lessons’ could possibly help us today. And at the same time, certain recordings, like those by Alexis Zoumbas, just humble me with their overwhelming majesty and power. Each time I listen to them they are fresh, full of mystery.

Did you have a specific audience or an ideal listener in mind when you made this compilation?

Actually, this collection is addressed to all of humanity; anyone who happens to be intellectually curious and has a capacity for listening deeply. I think we all have an innate disposition to be profoundly affected by music but there are quite a few people that are naturally receptive to the notion that music can be transformative. Obviously this music is not merely for entertainment, like the vast majority of popular forms that exist now. I think that is the key to this music – it has intentions that are much deeper than just ‘listening’ or being entertained. Ultimately, it is a tool for survival, and we all need such tools.

In the liner notes you specifically describe the context of this music and its function in the community it was born into. How do you think these tunes work in a completely different context, such as today’s western society?

I travel to Greece whenever I can, especially to attend ‘paniyeria’ in Epirus. So, I’m able to compare the context of ‘what was’ versus ‘what is’. Even though 21st century rural Greece is different from the mid to early 20th century rural Greek countryside, there are enough similarities to convince me that the function is still in the music and the context within the village is recoverable. In central Zagori, for instance, in the village of Vitsa, this context still exists and the music is felt very deeply, as if it is medicine. There has been a strong feeling of cultural identity for many generations and a refusal to assimilate completely with the mandates of globalism, Europeanisation, and what I call ‘creeping suburbanisation’. Of course, Greece is still culturally tied strongly with the Greek Orthodox Church, with traditional values, and with its own unique deeply felt notions of identity. Therefore, even though the context has changed, there is no reason to believe that it cannot be reconstituted, valued again as something uniquely ‘Greek’. The music and the culture of rural Greece, especially in Epirus, is an immeasurably invaluable cultural asset that no other European country has. It is a source of pride and identity.

![]()

There is an almost mystical, ‘healing’ purpose to this music. What kind of wounds would it heal today?

I think the curative, calming, ‘healing’ function of this music could heal any number of spiritual or psychological injuries. It has been powerful medicine for thousands of years. For instance, the playing of the traditional mirologi at the beginning and at the end (especially the end) demonstrates the kind of awesome power of this music to those who listen deeply, who know what to listen for. When I hear a mirologi or a skaros played with the right touch, I feel an unwinding within myself, as if the bad kinks and knots and heartbreaks are rearranged, put in proper order, healed. But I don’t think that this reaction is too rare: most people, if they allow themselves to be healed, will feel what the music has to offer.

What projects do you have lined up next?

My main focus until the fall of this year is to complete the drafting of my first book, Lament From Epirus, for publication by W.W. Norton and Company. It is essentially a music travelogue, where I combine philosophical inquiry, anthropological investigation and historical research to tell the story of the ancient music of northern Greece. As soon as the drafting is done, I will be issuing a collection of Kitsos Harisiadis’ recordings as well as a two-disc collection of early Asia Minor music from 78s in my archive. I also hope to produce a ‘companion’ collection of music and video to be issued with the book next year. I have at least another five collections in mind of early Greek music. Finally, I will be working with various cultural organisations in Zagori to bring well-managed ‘cultural tourism’ to the region.

What made you become a collector?

I’ve been a collector of these old 78s since I was 15 years old. My father was a collector and he helped me out but it really wasn’t until I found a small stack of incredible black country blues and religious recordings from the 1920s in a shack on my grandparents’ property that I discovered what I was really searching for. Ever since then, I’ve been searching for ‘that sound’.

If not for you (and others like you), these recordings would possibly be lost in oblivion. How important is it to you to discover such recordings, preserve them and present them to a contemporary audience?

This has been my whole life. And, if my luck holds out, it will continue to be my main obsession and livelihood for the rest of my life. It is hard for me to imagine doing anything else. I see this particular human activity of exploration, preservation and dissemination of early folk music as both deeply rewarding but also relatively harmless. Who could ask for a better job?