Late last year I was standing in the old Memorial Hall at Koonwarra in South Gippsland looking at a photograph of a young digger – one part of the Hellenic link to Australia’s Anzac story. The photograph was of John Joseph Sperling and is part of a framed Anzac memorial put together after the end of the WWI honouring some of the young local men who had left to take part in a war on the other side of the world.

Vera Dowel of the memorial hall committee kindly shared the hall’s history and that of the tree nearby, grown from a seed from Gallipoli. To think that this wooden hall erected in 1892 had stood as the young volunteers left the area to enlist, and it had stood as the families welcomed their loved ones home – or learned of their loss on the battlefields far away.

Invited to address the South Gippsland Hospital Auxiliary 80th Anniversary Dinner on the role of Lemnos in the Gallipoli campaign, I took the opportunity to research the area’s connection to Lemnos. One of those connections was John Sperling.

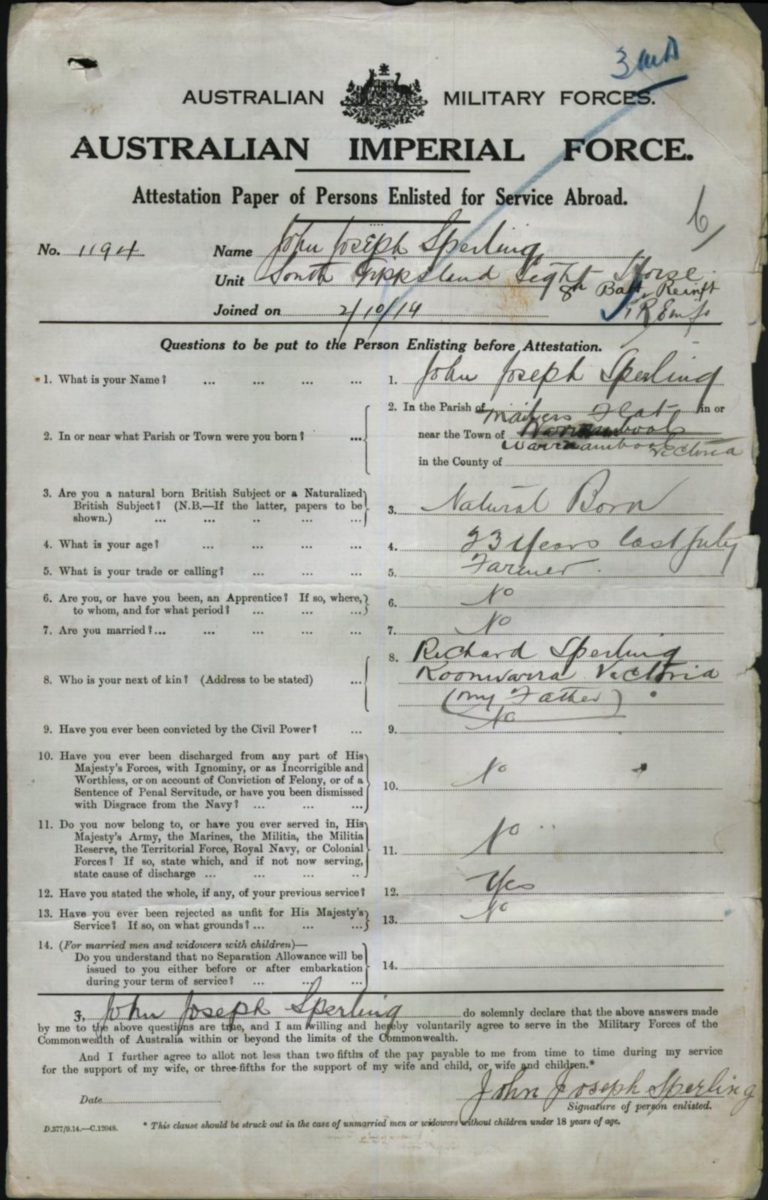

John was a young man, just 23 years old when he signed up with the Australian Imperial Force on 2 October 1914 at a recruitment centre in the nearby town of Leongatha. John had been born in a small town just outside Warrnambool on Victoria’s coastline. The family moved to establish a farm in Koonwarra in 1902 and named it Fernshade. John had six siblings and by the time he enlisted his mother had died and the family was being cared for by their father Richard.

During my visit I met one of John’s relatives who still lives in the area, Phylis Davison, who told me that although he had lived on the farm, farming was not for him. Maybe that was one of the reasons that drove John to enlist, and it’s no doubt his experience with the Leongatha Rifle Club would have put him in good stead when he signed up.

Private John Sperling sailed with the rest of the 8th Australian Infantry Battalion from Melbourne’s Princes Pier on 22 December 1914 – not far from the site of Melbourne’s new Lemnos Gallipoli Memorial.

He left Australia on a troopship named after the 5th century BCE Athenian politician and general, Themistocles and his journey brought him to Lemnos’ Mudros Bay on 11 April 1915. As he entered the bay, John would have wondered at the mass array of naval vessels, readying for the coming landings at Gallipoli, some 200 ships.

The Battalion diary reveals that John spent his time on Lemnos practising disembarking and landing on the shore, as well as marching across the hills that surrounded the great bay. I wonder if these hills reminded John of the fertile hills of Koonwarra. Many diggers wrote of the flowers that covered Lemnos’ hills at the time.

John landed at Anzac Cove as part of the second wave on 25 April. He took part in the battles defending the beachhead before the battalion moved south to take part in the disastrous battle to capture the former Greek village of Krithia at the southern end of the peninsula.

While John survived these engagements he would be felled by the diseases that plagued the soldiers at Gallipoli. The lack of proper sanitation arrangements gave rise to serious and often fatal gastric disorders. John was taken from the trenches on 29 June 1915 suffering serious diarrhoea and was eventually transferred to one of the many field hospitals established around Mudros Bay. He died on 8 July, two days after returning to Lemnos.

While the army had informed John’s family in Koonwarra of his death, there was initial confusion as to his fate. His father had received information in January 1916 that John had been seen alive in October the previous year. Sadly these hopes would be dashed.

It was my pleasure to meet Phylis and another relative of John’s, Jennifer Cross, during my stay in South Gippsland. They told me of how the Sperling farm remains in Koonwarra and they took me to the Koonwarra Hall to see John’s photograph.

It is moving to see how the impact of Gallipoli has an impact on families to this day. When Phylis met me at the hall she brought along the original photograph of John’s grave at East Mudros sent to the family by the authorities after his death. These are rare photographs, many have lost with the passage of time, and they show the original wooden crosses erected on each grave, before their replacement by grave stones after the war.

Of course John was just one of hundreds of diggers from Gippsland who served in the First World War. One of his comrades in the 8th Battalion was a 22-year-old labourer from Lakes Entrance who had enlisted at Bairnsdale, Private William Carstairs. He had departed Melbourne on the Themistocles with John, and were ultimately buried on Lemnos too.

Other diggers from Gippsland who were buried on Lemnos were Cowes-born postal worker, Lance Corporal Raymond Thornton, 22; Coalville-born Private Benjamin Ashton, 22; and 21-year-old Tinamba-born Private John Searle. Private Searle departed Brisbane aboard the troopship Aeneas, another example of the many classically-named troopships and warships engaged in WWI.

This story of war, suffering and care had a resonance with my visit to South Gippsland. My address to the auxiliary told the story of the dedication of the Australian nurses and other medical staff on Lemnos in 1915. How very relevant to a community organisation that has raised thousands of dollars to firstly establish the hospital and then to support it with vital medical equipment over many years.

One locally-connected digger who travelled to Lemnos and survived was Lieutenant General Sir Stanley George Savige, KBE, CB, DSO, MC, ED. Born in Morwell and raised in Prahran, Stanley sailed from Port Melbourne aboard the troopship Euripides in May 1915. He sailed into Mudros Bay in September 1915, narrowly missing being torpedoed by an enemy submarine. He survived the battles on the peninsula and returned to Lemnos after the evacuation, enjoying the Christmas celebrations that took place at the Anzac camp at Sarpi (modern day Kalithea) on Lemnos. To follow Stanley served on other fronts, including saving thousands of Christian refugees in southern Persia. He returned to Greece in 1941 and helped establish the war widow’s organisation Legacy after the war.

This link to Greece is commemorated at the impressive Korumburra War Memorial, the gates that mark the entrance erected in Stanley’s honour.

Having personally stood before John’s grave in the Allied war cemetery at East Mudros, talking to his relatives I was able to tell them how well the graves are maintained, and that the locals also holding an annual service in honour of the soldiers and nurses who came to Lemnos from afar.

Driving back to Melbourne through the lush valleys of South Gippsland, I am drawn to the fact that there must be hundreds – nay thousands – of villages, towns and suburbs across Australia connected to Lemnos and Greece through the Anzac story. These Australians – relatives of diggers and nurses from distant wars – share this personal connection, linking the story of their family members and Greece. John Sperling is one of those stories.

As I stood before John’s grave beneath the hills of Lemnos during this year’s annual commemorative service at the East Mudros Military Cemetery, I thought of a farm in Koonwarra in far away Gippsland – and a grieving family to whom this son would not return. Lest we forget.

* Jim Claven is a trained historian and freelance writer. He is currently in Greece participating in various commemorative services, including the erection of the new memorial at the Australian Pier on Lemnos on 20 April. He would like to acknowledge the support of Trish Shee for inviting him to South Gippsland to the Leognatha Historical Society and Colin Leviston for sharing the photo of John Sperling, to the extended Sperling family for sharing their stories and archive, in particular Jennifer Cross, Phylis Davison and Mervyn Williamson. And finally to his fellow researcher Suzanne Coburn who has assisted the Sperling family in researching John and their family’s story.