This month the annual commemorations of the Greek campaign of 1941 will culminate in a series of events on Crete and in Australia marking the 77th anniversary of the battle of Crete. Australia played a key role in the battle, along with Greece’s other Allies.

For many years I have walked across Greece, visiting many of the sites connected to this battle and those on the Greek mainland. One of the places I visited was the Monastery of Preveli on the southern coast of Crete.

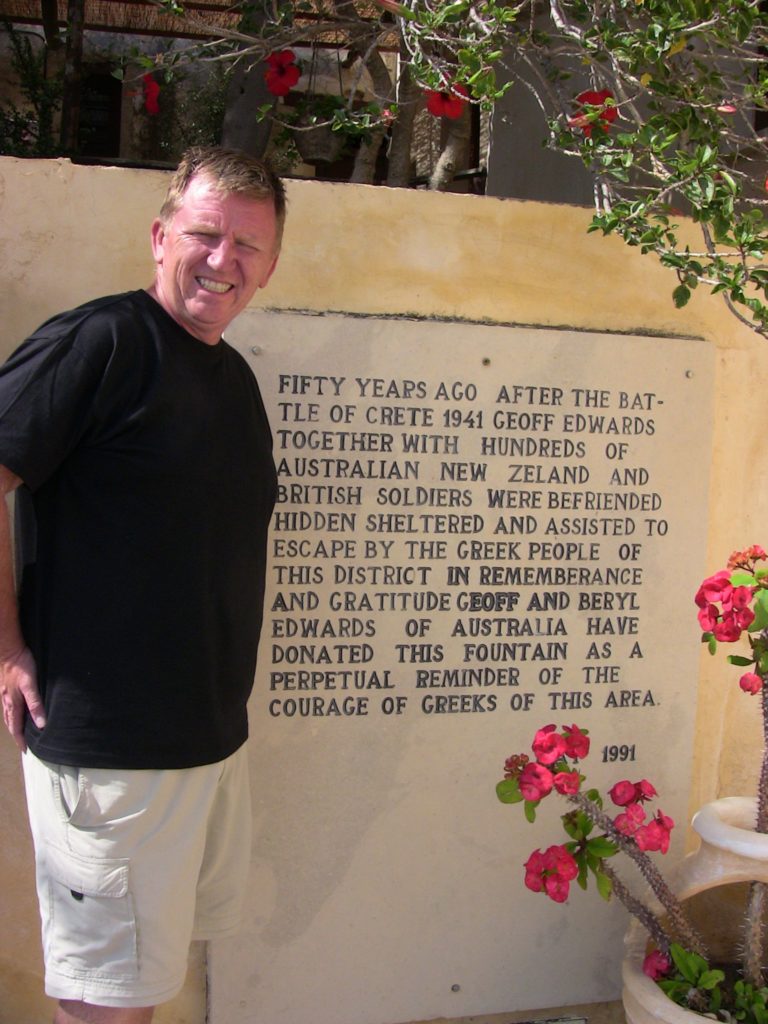

As I walked through this beautiful monastery I came across a water fountain dedicated by an Australian soldier and his wife who had come here in 1941. He was Geoffrey Edwards. Geoffrey was one of many Allied soldiers who had found sanctuary and support amongst the monks and surrounding villages as they evaded capture by the victorious Germans.

They were sheltered by the locals until they were able to be evacuated to safety in Egypt from the nearby beach. The dangers to the Cretans of sheltering these young foreign soldiers is evidenced in the physical destruction of parts of the monastery when the Germans came to exact their revenge. Parts of this destruction have been preserved. Thankfully, the head of the monastery, Reverend Father Laggoubardou, was persuaded by the Allied soldiers to come with them, so certain were they that he would be killed for his support.

Years after the war, these same Allied soldiers would return to Preveli Monastery and help in its restoration, including the small water fountain, dedicated to the people and monks of Preveli who helped the Allied soldiers in their hour of need. Geoffrey would go on to build and dedicate a Greek Orthodox Church in his native Western Australia, gifting it to the Greek community and renaming the area Preveli.

It is stories such as these that have always struck me. They reveal the intensely personal core of the Hellenic link to Anzac. The Second World War was endured for close to six long years, and would see Australian soldiers engaged in combat across many theatres. Those who fought in the Greek and Crete campaigns of 1941 had also served in the Middle East and many would return to this theatre and others in Pacific.

Yet for many of these soldiers, their experience in Greece and Crete would never leave them. The campaigns had lasted only a few weeks, for those on the run a few months, and for a few these would extend to a year or more. What I have found moving is the fact that despite many soldiers having served in Greece for short periods, they would recall their experiences for many years afterwards.

I am reminded of the experience of Private Syd Grant from Victoria’s western district. He served in the Middle East with the rest of the 6th Division and went on to serve throughout the Greek mainland before being evacuated to Crete. He would survive the war and return to Australia.

In his memoirs recorded years after the war, Syd talked of his evacuation from the Greek mainland, of his failure to gain passage on a ship from Kalamata, his capture and escape to the villages of the Mani. He spoke of being protected by the villagers of Trachila until his evacuation by submarine.

Similar stories from the Australian experience of Greece stretch back to WWI. Families who had lost a son or father at Gallipoli and whose loved one was buried in the Allied cemeteries on Lemnos, would rename their homes ‘Lemnos’. And one digger from country Victoria, Ernie Hill, who served with Victoria’s famous Albert Jacka VC, would successfully lobby for the soldier settlement outside Shepparton to be named simply Lemnos. No doubt Ernie was keen to remember the care and treatment that he and thousands of other Allied soldiers received at the hospitals on Lemnos, as well as the hospitality of the local Greek villagers of the island.

This for me is what is most valuable and telling in the Hellenic link to Anzac. It is the connection between peoples. It is how, amidst the horrors and threats of war, human kindness and friendship shines through and endures.

PhotoS: Jim Claven.

We see this in the many touching photographs taken by the Anzacs during their service in Greece. We see it in the beautiful photograph of two villagers in the village of Tsimandria on Lemnos in 1915 taken by Australian Albert Savige, in Syd Grant’s photograph of the women of Trachila bringing food to his hideout in late April 1941, and in his photograph of a fierce-looking elderly Cretan after his evacuation there, with the touching note on the back by Syd that the old man loved “the plonk”! And we can see it in the documentaries of my good friend John Irwin who is currently in Crete interviewing local women who helped the Anzacs during WWII for his forthcoming documentary Out of Their Own Hands – Women of Crete and the German Occupation 1941–44.

Yes, the battle of Greece and Crete brought terrible destruction to millions of lives, for both soldiers and civilians. And this disruption stretched all the way back to Australia, to the homes and families of those who would never return and those who returned forever changed by the experience. Yet as I am trying to explain this is only part of the complex human experience of war. Thrown together by the violence of war, human beings also demonstrated their common humanity, from Lemnos in 1915 and through Greece and Crete in 1941 and beyond.

I have been asked many times from where my interest in the Hellenic link to Anzac comes from; it comes from many sources.

One of my seminal experiences was as a young migrant attending Melbourne’s Prahran High School in the 1970s. Recently arrived from Scotland, I became immersed in the multicultural population of the school. Many of my fellow students were of Greek or Cypriot origin or heritage. As an outsider in Australia, I enjoyed their customs and food. And there were Australian-born students who introduced me to Australian culture and ways.

It was also at Prahran that I first studied Ancient History, including that of Classical Greece. I would go on to further this interest during my history degree at Monash University.

On a personal level, I have always been fascinated with my own family history. Many migrants have a similar yearning to connect with what seems distant and lost in time and place. I have spent days in Scotland’s archives in Edinburgh, searching through births, deaths and marriages, going back to the 18th century. But what I find sad is what is lost and cannot be replaced.

In this I think of my maternal grandfather. An orphan at a young age, John Dunnion would serve in the British Army in the First World War. He would survive that terrible war, work all his life, raising his family in his native Glasgow. He even tried to volunteer in the Second World War, eventually being allowed to serve as an air raid warden. I never had the opportunity to talk to him about his experiences as he passed away while I was a young boy. But what is worse is that John’s medals and personal photographs and records were all disposed of by a disinterested family member upon his death. I wonder what they might have recorded for me and the history – pre-war photographs of Glasgow, photographs recording his time as a soldier on the Western Front and later as a prisoner. In my mind’s eye, I can remember being shown one image of my granddad in the German POW camp, now lost forever.

It is for this reason that I encourage many I meet to donate their photographs and other family records of the Greek and Crete campaigns to archival institutions such as Melbourne’s State Library of Victoria. I know of many such collections that are yet to be shown to the public, held in private homes, cherished by surviving family members. As a historian, I know that many of these images and stories will enrich our knowledge of the Hellenic link to Anzac – and so much more.

It has been a real pleasure to have been taken on this journey of discovery. I have met many wonderful and interesting people along the way – in Australia, in Greece and beyond. Many have shared their personal family stories with me and allowed me to share them with my readers. My writings are dedicated to all of these lovely people. Without them my research would have been all the poorer. Thank you and lest we forget.

Jim Claven is a trained historian with degrees from Melbourne’s Monash University, a freelance writer and member of the Battle of Crete and Greece Commemorative Council. He is currently working to realise the creation of an Anzac trail throughout Greece, linking existing WWI and WWII memorials and to create new ones, to assist descendents and commemorative visitors and to bring a new source of visitors to Greece. He can be contacted at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au