Sailing the northern Aegean in late summer is a beautiful thing. The deep blue water and the brilliant sun combine with amazing sunsets. It’s hard to imagine that these waters contain danger.

In September 1915, a large transport ship was sailing across these same waters, having left Alexandria in Egypt bound for Lemnos’ Mudros Bay. Aboard were thousands of Australian troops, including the men of the 6th Brigade.

These men were Victorians, including their commander Colonel Richard Linton, a Scottish-born resident of Brighton, Melbourne. Two of the diggers aboard the ship were new arrivals to Australia, the Sloan brothers, James and Thomas. Along with their family; parents Elizabeth and William and their siblings, they had emigrated from Glasgow in Scotland to make Melbourne their home in 1913. Like the waves of post-WWII Hellenic migrants who came to Australia, the Sloans no doubt hoped for a new and prosperous life for their family.

James and Thomas had been educated at Glasgow’s Sir John Stirling Maxwell School; famous for its education of the children of working people and for one of its teachers, the socialist activist John Maclean.

Soon the family was living in Box Hill, at 22 Kangerong Street, just off Whitehorse Road. Their house still stands. James and Thomas would soon find work at the nearby brickworks in Mitcham and Blackburn.

Opposed to war and conscription, John Maclean was arrested in distant Glasgow. But the Sloan family answered the call for volunteers to serve Australia and the Empire; they had been in Melbourne barely a year when war had erupted. Four of the family would join up: William and three sons James, Thomas, and William jnr. They are part of the 30 per cent of all the diggers who volunteered in WWI who were born outside Australia.

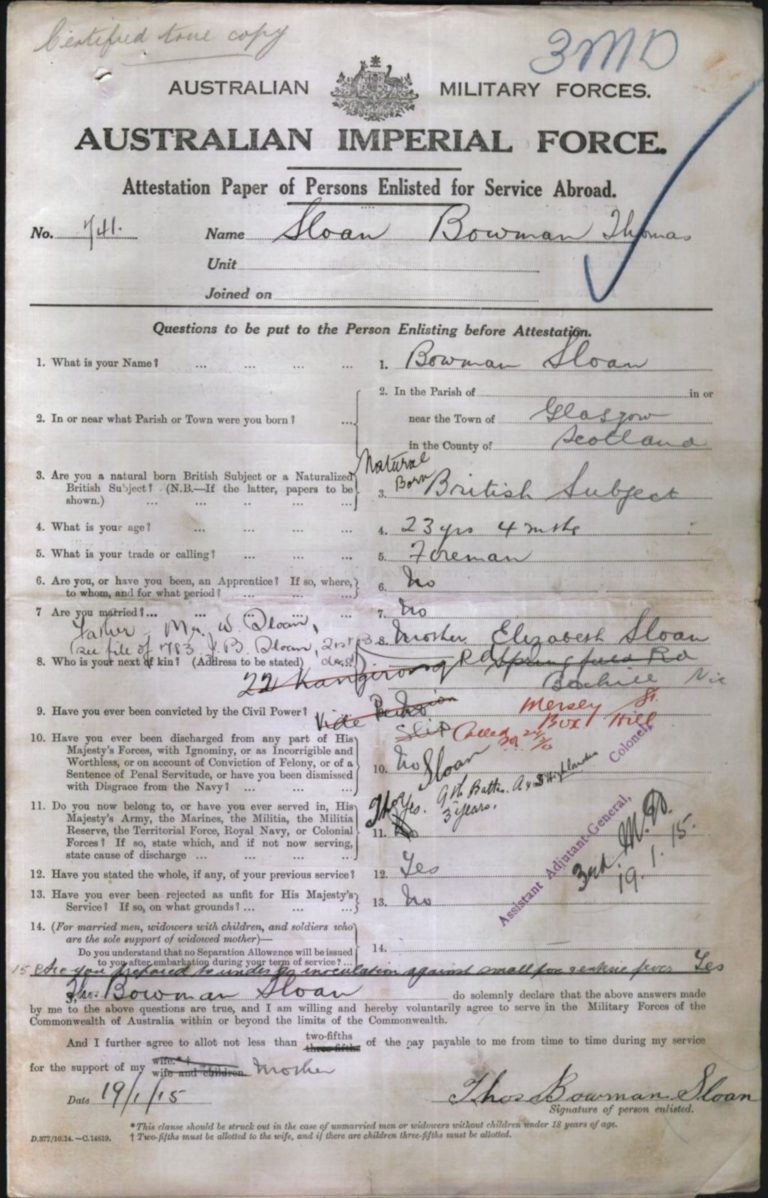

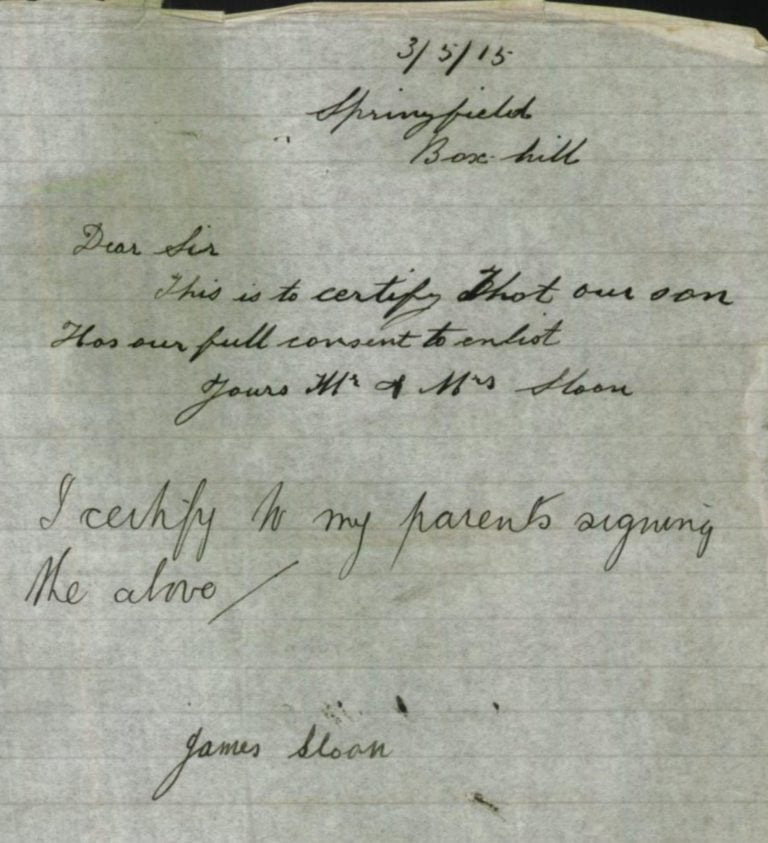

Thomas joined up on 19 January 1915, followed by James on 3 May 1915. James was under 21 years old and needed his parents’ consent, which was duly attached to his enlistment file. They would both sail from Australia as privates in the 21st Battalion. They were “characters” as one of their comrades later remarked and served in the battalion’s band. Their father William and their younger brother William junior would subsequently enlist. They left Australia aboard the troopship Demosthenes on 16 July 1915, and after a period of training in Egypt, they boarded the troopship Southland headed for Lemnos and ultimately Gallipoli.

And so it was that the Southland steamed across the waters of the Aegean. The troopship made the two day journey, zigzagging its way through the sea to avoid a danger of the deep – enemy submarines. These German submarines had been active in the Aegean soon after the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign. They already sunk the great battleships HMS Triumph and HMS Majestic off Gallipoli and had attacked the troopship Manitou, and they would sink more.

It was reported to have been “a cloudless, sunny morning, with a fresh breeze and a choppy sea” as they sailed north towards Lemnos on 2 September 1915. Some diggers on deck reported that they could see the small Island of Agios Efstratios lying to the south west of Lemnos.

Suddenly the calm was broken at 9.45 am by the crash and explosion of a torpedo from a German submarine hitting its mark on the port side of the troopship. A large hole had been torn in the side of the ship. Some diggers were killed instantly. The ship shuddered and began to fill with water, the SOS was issued and rescue ships made their way to the area.

The troops are reported to have been disciplined and in good humour as they prepared to be evacuated. One played a piano and others are reported to have sung songs as they waited. Nonetheless lifeboats soon tipped over while being lowered, and some boats capsized in the swell, tipping their occupants into the open sea. Many diggers were seen “struggling in the water.” This was the fate of the Sloan brothers.

Eyewitness accounts from other diggers report what happened. While the accounts vary on details, all agree that both brothers drowned together. One recalled how they jumped into the sea, “kept together in the water and were seen by several . . . to sink together.”

Another that they were both in a lifeboat that capsized while being lowered into the sea. They became trapped under the upturned boat. Here they would drown – despite wearing lifebelts and the efforts by another digger, Private Broochi of the 21st Battalion, who “dived three times under the boat to try and save them but could not get them from under.”

Some 40 Australians were killed or drowned in the attack on the Southland, including Colonel Linton. Reported to be “a strong swimmer”, he died of exhaustion after spending over an hour in the water, all the while urging his men to be taken from the water first. Taken from the water alive, he would soon die and be buried on Lemnos – the most senior Australian soldier to be buried there.

And yet the rescue mission was an overwhelming success. Over 1,450 men were saved, most on rescue ships which sped to the scene. One of those who survived that day was the 21st Battalion’s young Private James Martin from Hawthorn, who was only 14 years old – Australia’s youngest Anzac. Even the Southland was saved, limping into Mudros Bay, thanks to the brave work of 18 diggers who volunteered to act as stokers in the ship’s engine room. She would be repaired and sail again – and the survivors would go on to leave for the killing fields of Gallipoli.

Back in Melbourne, James’ and Thomas’ brother William junior was days away from departing Australia. On 10 September 1915 he boarded the troopship Star of Victoria and sailed from Princes Pier at Port Melbourne – the same pier that his brothers had departed from two months earlier. Their mother Elizabeth and sister Mary would be granted dependent status in 1916 and awarded war pensions. William would not serve outside Australia and was discharged on 19 July 1916 owing to his being “over military age.”

William junior would serve at Gallipoli and the Western Front. He even came to Mudros Bay on Lemnos in December 1915 – the destination that his two brothers never reached. He would be wounded in France and be Mentioned-in-Despatches: “for participation in a very successful raid on the enemy trenches on 30 September 1916.” He would survive the war.

And how are these two young Scots-born Australians remembered? Unlike Brigadier Linton their bodies were never recovered and so they are not buried on Lemnos. The names of the Sloan brothers are engraved on the great Helles Memorial to the Missing that stands at the end of the Gallipoli peninsula. And their names are also listed on the War Memorial in Box Hill.

It was a proud moment for many of us in the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee to take part in the Royal Australian Navy’s commemorative service aboard HMAS Success anchored in Mudros Bay in April 2015. I thought how touching for those diggers who had been lost at sea – like James and Thomas – to have Australia’s navy return to these waters 100 years later to commemorate the service of all those who served in the Gallipoli campaign.

Standing outside their former, and now sadly derelict, home in Box Hill, I tried to imagine what the house would have looked like in 1914. It would have been an impressive home, not fancy but solid. Its weatherboards would have been new and painted. Smoke would have risen from the chimneys as Elizabeth Sloan made a farewell meal for each of the family as they departed to enlist. I’m sure there would have been an emotional scene as the family of 10, maybe joined by friends and workmates, rose to say goodbye – not knowing whether they would ever see them again. And so James and Thomas strode through this doorway in Box Hill – never to return. I hope that this little home, with its tangible connection to the diggers who came to Lemnos in 1915, is restored and not lost to posterity.

So next time you are sailing on your ferry across the beautiful Aegean, awaiting arrival at your island destination, think of the Sloan brothers from Box Hill who sailed these same waters, never to return and their grieving family at home in Australia.

Lest we forget.

*Glasgow-born Jim Claven is a trained historian, a freelance writer, and the secretary of the Lemnos Gallipoli Commemorative Committee. He has researched the Hellenic link to Anzacs over a number of years, led commemorative tours on Lemnos and across Greece, and is now preparing a major new pictorial history of Lemnos’ role in the Gallipoli campaign. He can be contacted at jimclaven@yahoo.com.au