The coincidence was inspiring. While organising an interview with one of the most prolific photojournalists of our times, the Greek Australian Walkley winner, Mick Tsikas of the Australian Associated Press, my free time was spent getting immersed, once again, in the story and craft of Gustave Flaubert’s masterpiece Madame Bovary. The pioneer of literary realism is famous for his struggle with every sentence, for the length of time it took him to orchestrate and finish a scene, his enchantment with precision and his aptitude to transform cynicism to art.

And that is exactly what Mick Tsikas has been doing with his photography for the last three decades. Armed with a sense of humour to die for, a cynical view of the political elite –who can blame him for that?-, an obsession for precision and aesthetic harmony, more than 30 years of experience, his pathos to document the story from every possible angle while it is happening, and his keen eye for detail, Tsikas deserves to be called the Flaubert of Australian photojournalism.

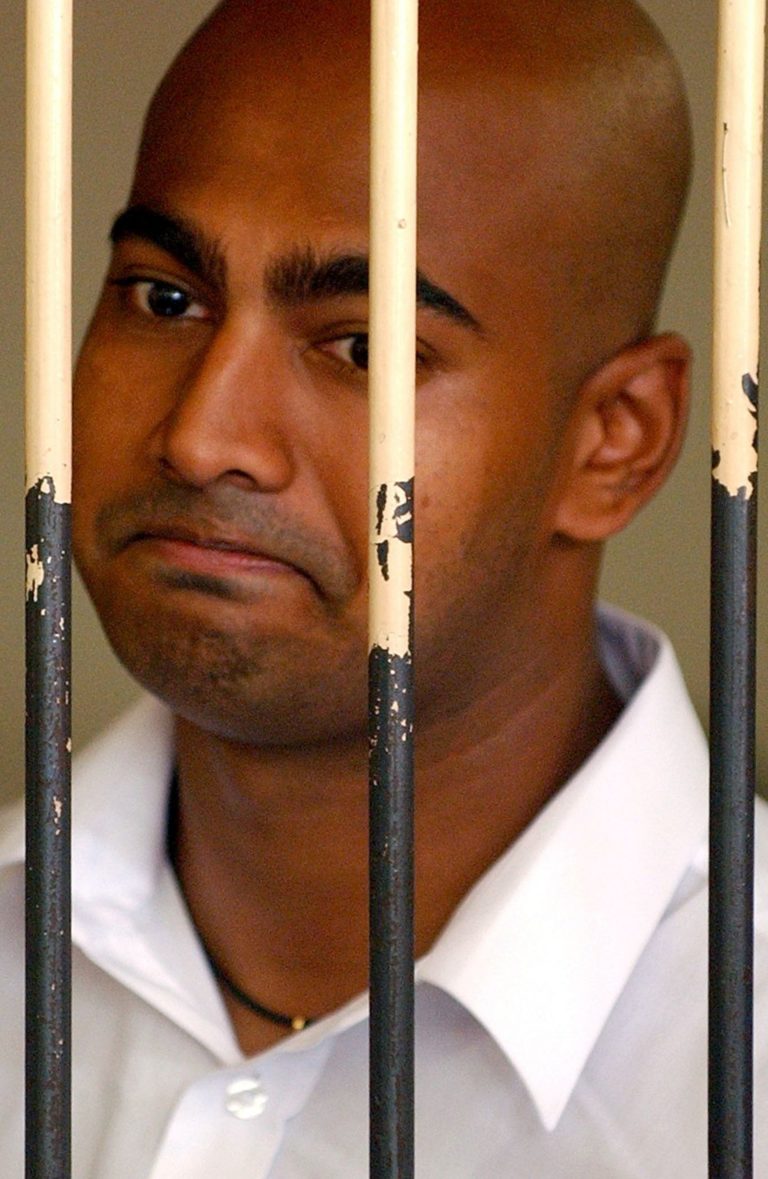

His sharp eye keeps politicians awake at night. He can read through their media-trained faces and reveal the truth behind the theatrics. In front of them his lens is nothing less than ruthless. He is also the photojournalist who won a Walkley award in 2005 after photographing the Bali Nine following their arrests for drug offences. He chose to spend three weeks in tsunami devastated Aceh in 2004, witnessing the unprecedented disaster, breathing and living the pain nature inflicted on the poor people of Indonesia.

His photography capturing human tragedies is nothing less than a hymn to humanity, a narrative of sheer empathy, compassion and lyricism that has nothing in common with his political photojournalism.

Mick Tsikas is a brilliant photographer and an accomplished artist. He is also a fascinating person. The following interview proves why.

Who is Mick Tsikas and when did you start photography?

I am a photojournalist with AAP. I was born in Sydney in 1966 and my parents come from Ioannina. I am a father of a boy and a girl and I did go to University but I did not stay. Photography came to me early, in my first year of High School. We had arts and they got us in a dark room. Personally, I did not know what was going on. So they turned the lights off and the red light came up. They took a piece of paper they put it on the desk and they put on it screws and nails. They turned the light on and off and then they put this piece of paper in the developer and… magic! It was my first thought when I saw that photo. That was it. I got hooked. And to this day, photography remains magic for me. You capture an instant moment forever. When you take a photo, if it is a good one you realise that you have done something special. It is like writing history. Photography is really the first draft of history.

I started working as a photojournalist at the Sydney Morning Herald in 1995. Since then I worked for the Daily Telegraph paper, Reuters and now I am in AAP.

In my photos, I want to show that it is not only one person in any story. It is like the ancient Greek stories. There is a hero. There is a villain, there are those who lose and those who win. That’s why I photograph the reactions of other people who, while silent, they actively participate in the story.

Are elements of your character manifested in your work?

I would say a lot. I see my photos as precise, an effort to capture a certain moment at that instance with accuracy. I am also a very cynical person. I am trying to see with my photos through the politician’s spin and yes, I use humour to do that. I think I am funny. My girlfriend says so, my kids don’t think so. You know, politicians take themselves too seriously. I try to skew it a little bit and make them look funny, in order for them to look more interesting. So yes, I am humorous, cynical and precise.

These qualities though do not appear in your human story news photography. Looking at the Bali Nine photos, that you won a Walkley award for, the empathy and humanity that they exert is extraordinary. No sign of cynicism there; just sheer empathy.

I think I am very lucky and I take that as a blessing that I get to see these things and to tell these stories. And I think it is important to do it humanly and with pathos. When the Bali Nine were arrested and charged for heroin trafficking, everybody back then was saying “execute them.” What I saw though was a group of 19 year old kids who made a mistake. Why should they die for making a mistake? I made many mistakes when I was 19. You did too, but we did not die. I, through my photos, was saying, ‘hold on, they are someone’s children, someone’s brother, someone’s grandchild, they do not deserve to die’. The same thing happened when I went to Aceh. I was given the honour to photograph one of the worst disasters of the century. When I went there, I was there for three weeks, if I didn’t like it, I could call the boss and he would say, ‘no problem’. They will put me in a five star hotel, with my champagne, and relax. The people in Aceh, they did not have that privilege. So I felt it was my job to tell the world what was going on. It was my duty to tell the story with pathos and humanity.

Dead bodies everywhere, the stench of death all around you, total destruction and devastation, young men heading to their execution, parents saying the final goodbye to their sons knowing that when they will see them again they will be in a box. How do you cope with all this misery?

Like I said before Eugenia, it actually is a privilege for me to be there. It does change you, of course. It makes you realise that life is precious. Life is a minute by minute. One minute you are an ‘is’, the next minute you are a ‘was’. So every moment with my loved ones, my kids, my partner, are special moments and I savour them. Most people don’t. They consider themselves unlucky all the time. They live in Australia and consider themselves unlucky, while I live in Australia and I say this is paradise. I spent two weeks in occupied Palestine and I saw how people live. You realise how lucky you are. So no, it does not affect me, I see it as a privilege and a great honour to witness this and to tell the story about it. Like I said before, I have the luxury to be removed from those sombre situations. The people in Gaza can’t do this, the people in Aceh can’t do this, the people in Papua New Guinea, can’t do this.

What happened, let’s say the tsunami, I didn’t cause it. It was not my fault. A lot of people died and people have to see it because these people need help. For people to see it, I have to go. I see it as an honour not a burden to tell their story, because they cannot tell the story to everyone else. They can only say it to me and then I tell it to you. That’s my mission. God invented me to do this. That’s why I was put on earth. To show the public the truth and to give the voiceless a voice.

In relation to your political photography, some might say that you editorialise. You have been accused of trying deliberately to humiliate some politicians like Michaelia Cash, Tony Abbott, Peter Dutton. What is your response to these accusations?

I don’t think I editorialise. When I take photos, let’s say of Malcolm Turnbull, I will take five that he looks good and five that he looks silly. I submit the 10 photos to the editor, he puts them up on the site where you see it. So it shows him fine and as an idiot; I am not editorialising, I am giving a balance.

I was accused that when I took a photo of Michaelia Cash in the Senate estimates saying what she said, that I took this photo deliberately and I was after her. That is not correct. If a politician poses under a ‘reject’ sign what do you do? If a politician eats a raw onion, what do you do? If a politician comes out with his red swimming trunk, what do you do? Of course, you do take the photo. I didn’t put them in that position. I didn’t make them pull those faces, they did it themselves. I do not interfere with what goes on. I do not tell the Senator “pull that face, do this Senator, or don’t do this Senator.” I don’t even talk to them. I just take the photos.

Minister for Jobs Michaelia Cash at Senate estimates hearing at Parliament House in Canberra, Wednesday, February 28, 2018. (AAP Image/Mick Tsikas) NO ARCHIVING

June 2015, Τhe then Prime Minister Tony Abbott on his way to visit a small business butchers shop at Kippax Fair in Canberra. Photo: AAP /Mick Tsikas

A rather sarcastic shot of ex PM Malcolm Turnbull, showing his bewilderment after Question Time. Photo:AAP /Mick Tsikas

The word in Canberra is that politicians are scared of your lens. Is it true?

Yes, they are very weary. If you stay on long enough, you learn their mannerisms; you watch them all the time. They are also doing it to themselves. Barnaby Joyce, when the news came out about his girlfriend, he was doing it to himself, he rubbed his face, he was looking up and down lost. These are easy photos to take, because that is how they are feeling. You just have to keep watching them. That is the thing we see, things that most people do not see, because we look.

What are the elements of a good political photo?

A good political photograph is the one that narrates an action or reaction. It is capturing that interaction of people. You look at a good photo of people and you see that interaction. In my photos, I want to show that it is not only one person in any story. It is like the ancient Greek stories. There is a hero. There is a villain, there are those who lose and those who win. That’s why I photograph the reactions of other people who, while silent, they actively participate in the story. I want to show all the actors. That is what makes a good photo. As human beings, we sympathise with people naturally, so we see a photo, of people smiling and it touches us. That is speaks to you, plus a good light, plus a good interesting background.

And who is your favourite politician to photograph?

Tony Abbott. When Tony Abbott was ousted by Malcolm Turnbull I was crying for days. He was the best for photos. So many missed opportunities…