“I thought I knew what viral was, but I was wrong,” John Mavroudis says, laughing.

“I turned away from my Twitter and Facebook notifications for a day because I was so busy,” remembers the San Fransico Bay Area-based artist. “When I went back to my Twitter, I had gone from five notifications to 4,000 notifications. It was crazy!”

What had happened in the meantime was people sharing his latest work on social media, making it one of the most circulated images of the past few weeks, an illustration that caught America’s zeitgeist. Printed on the cover of Time magazine, the artwork depicts Dr Christine Blasey Ford, during the testimony she gave to the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing regarding Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination on Thursday 27 September. A professor of psychology at Palo Alto University and a research psychologist at the Stanford University School of Medicine, Dr Ford accused Kavanaugh, President Donald Trump’s pick for a seat open on the US Supreme Court, of sexual assault. For his illustration, John Mavroudis used words and phrases of her testimony to compose her image. ‘Her lasting impact’ is the headline of the relevant story and the image has already achieved iconic status, becoming an emblem of both the #metoo movement and the Trump opposition.

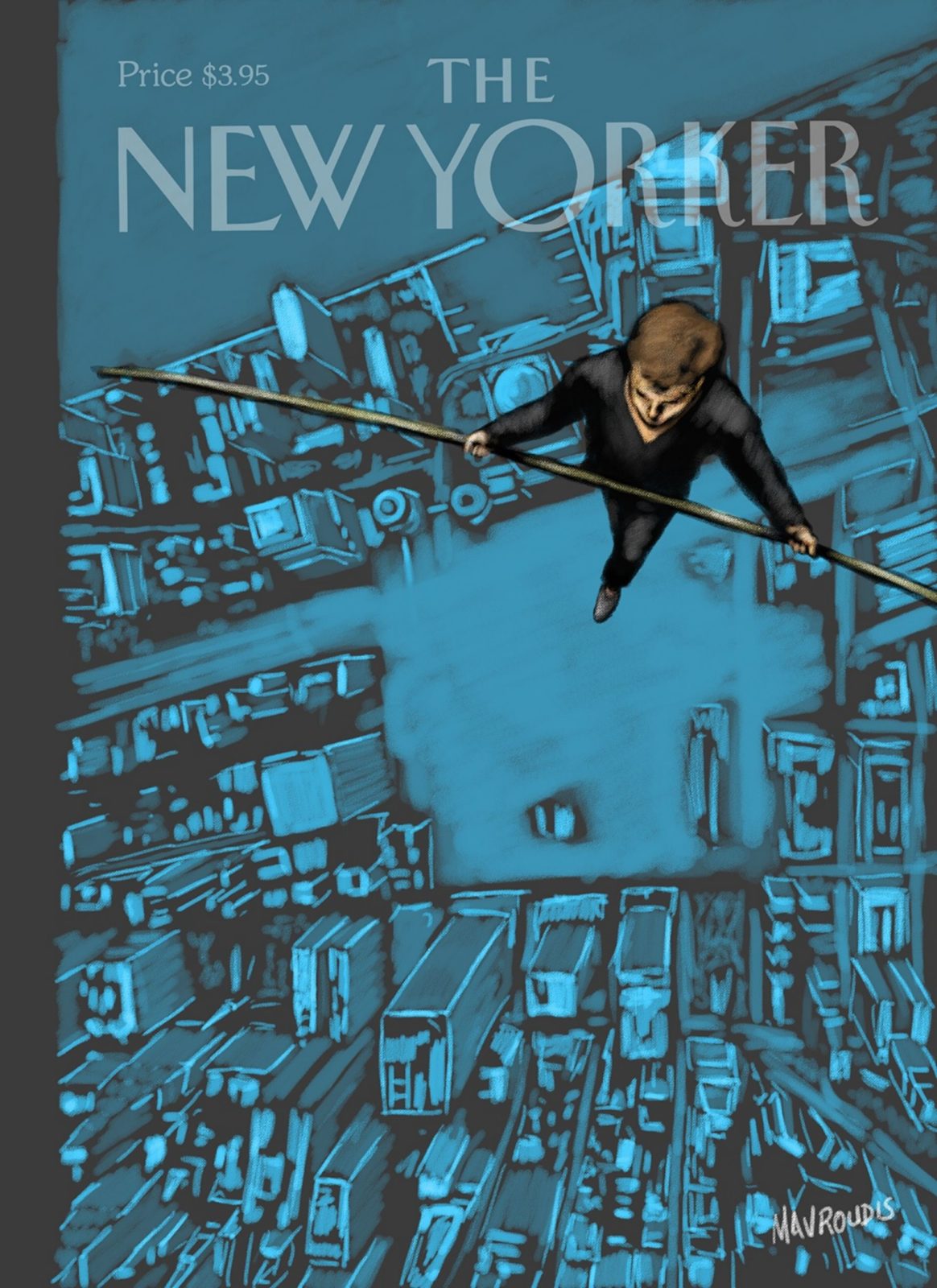

“I usually create on my own and submit to a lot of magazines and publications. If an idea strikes me, I will create it and submit it to New Yorker or The Nation, or any other magazine – or just put it on my Facebook page to represent some strong view I have, and if they pick it up, great!”

In the case of the Time magazine cover, things didn’t roll out this way.

“They reached out to me because they had seen some previous examples of a certain technique I have employed and they thought it would reflect well in this particular illustration,” he says.

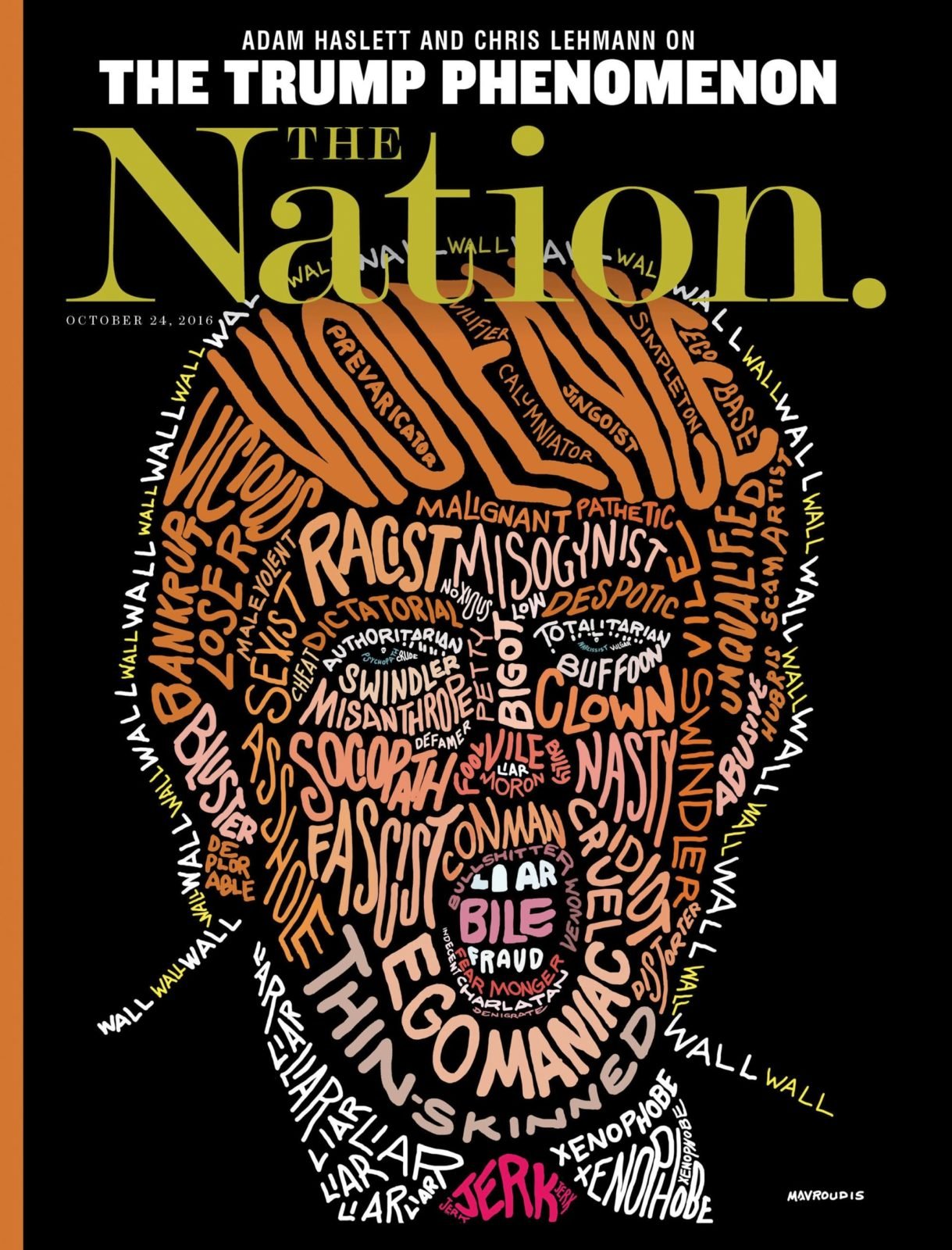

The example in question was a cover he did for The Nation, featuring Donald Trump’s image composed by words associated with his character.

“I listened to her testimony and it was riveting and heartfelt,” he says.

“I definitely believe her and Kavanaugh left me unimpressed with his defence. I think every case is different and people should look at the merit of the case but on the whole if you don’t have an open heart and open mind when you are listening to somebody who is making an accusation like that, that’s how we got stuck for thousands of years with women getting harassed.”

Working on an iPad with a digital pen, Mavroudis carefully selected the phrases he wanted to use.

“There were 20 or so phrases that I thought it was important to be positioned in certain places and then the rest I could build around,” he explains.

“I think about the eyes, the mouth, the hands, the forehead, the brain area and I think of what she said that could relate to those areas, what would be appropriate.

“Both the editors and I agreed that the more graphic nature of some of her accusations, were probably not necessary to put down. We could convey the message without retraumatising,” he says.

One of the most harrowing elements in the picture is the word ‘help’ positioned in Dr Ford’s mouth, where her teeth are – little white letters against black, the loudest cry depicted as a whisper.

“When I first did that I had the whole sentence: ‘I tried to yell for help’ and then I placed that on her upper lip,” says the artist. “I see a kind of desperation in her testimony; to me it was so riveting because she was so vulnerable when she was talking about this experience. Also, how she perceived the world that reacts to her – she said that she would be ‘anihilated’ for coming forward and in a lot of ways she was, her family received death threats.”

Asked how it feels to have created a modern iconic image, Mavroudis himself is trying to play it down and not get carried away. “I’m mostly in denial about that in some ways,” he says.

“I don’t know how impactful down the line in history this event will be but I think for now it seems to have really moved a lot of people. I’ve got a lot of feedback. It’s pretty amazing, actually,” he concedes.

Still, despite the powerful image, despite the movement in support of Dr Ford’s daring deposition, the Senate confirmed Kavanaugh’s nomination by a vote of 50–48; he was sworn in on Saturday 6 October.

“I think in a lot of ways, this moment exposed how far we haven’t come,” Mavroudis says.

“I think it’s not going to be too much longer to reach the moment we thought we were going to have with the Kavanaugh nomination. Because a lot of the same people are still in the Senate, a lot of the same tired faces have the same opinions that they had when Anita Hill [the attorney and academic who accused Justice Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment] was there. I think this November is pretty important on that score,” he adds, referring to the US mid-term elections, that many progressives see as an opportunity to restrict President Trump’s powers.

“I think that America can still have some positive impact when it comes to the rest of the world,” he adds with a kind of optimism that is rare when people talk about politics lately.

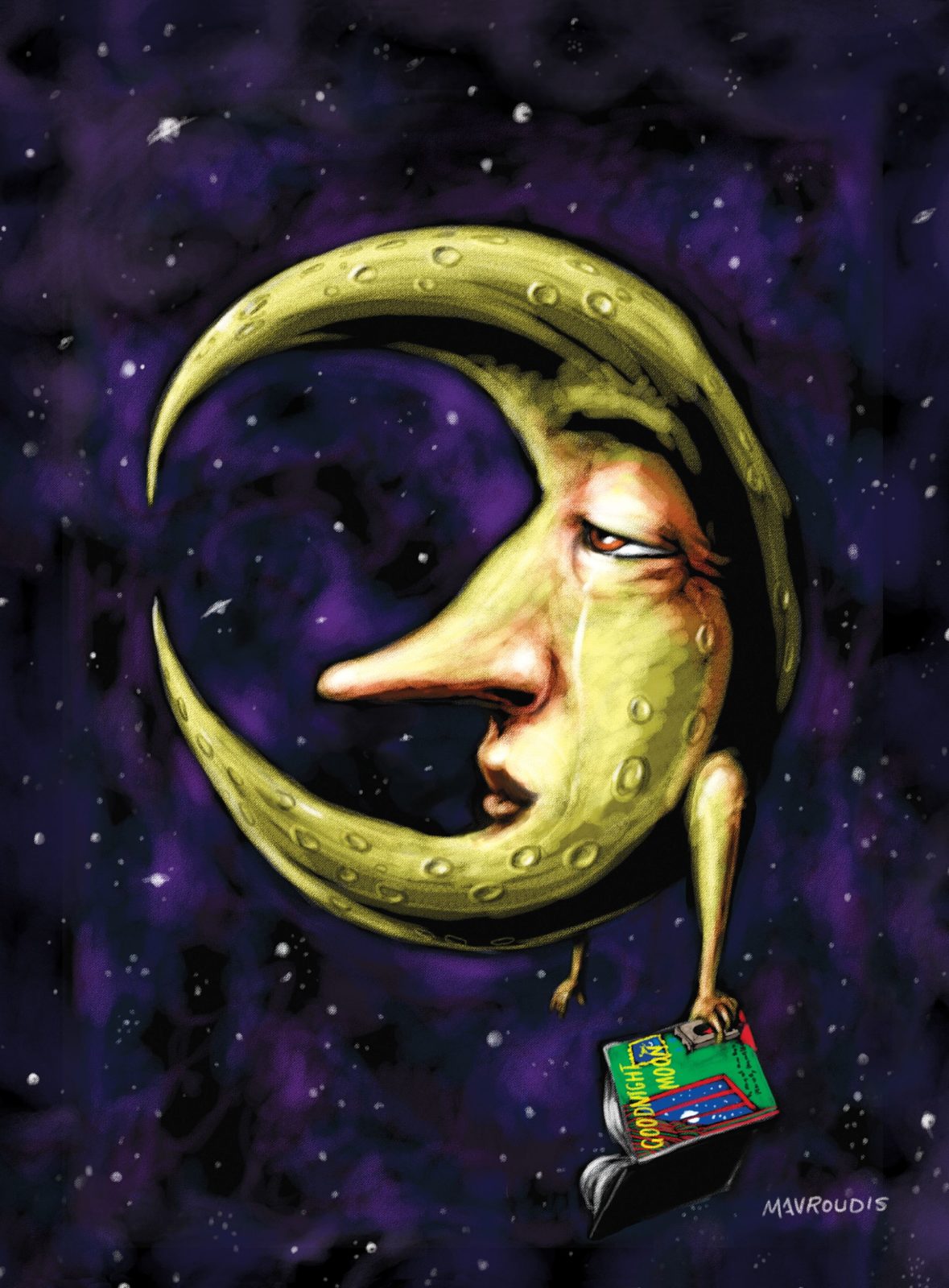

“I’ve always been kind of optimistic and I try to remain optimistic even at dark times,” he says. “It’s the only way to get through. If you are too pessimistic, it is a deterrent to keep pushing ahead for change.”

He draws from history to support this view.

“I get a lot of comfort in the fact that in the Women’s movement or in the Civil Rights movement in this country, there were many defeats, they went through horrible times. You don’t give up after one loss, you keep going. Even if Kavanaugh had been defeated, as helpful as it might have been, it still wouldn’t have been the answer. When Obama became president, he didn’t eliminate racism. These problems are never ending, it’s a constant struggle; If you want a better world you got to keep pushing to make it better.”

As an artist, what does he think that the role of art is within this context?

“I’m not original when I say this, but I do think that if you hold up a mirror to what’s happening in society and if you can create something that impacts people emotionally and intellectually, it is the best of both worlds. Art can be an inspiration, art can reveal truths, but art can be used as a weapon for bad as well.

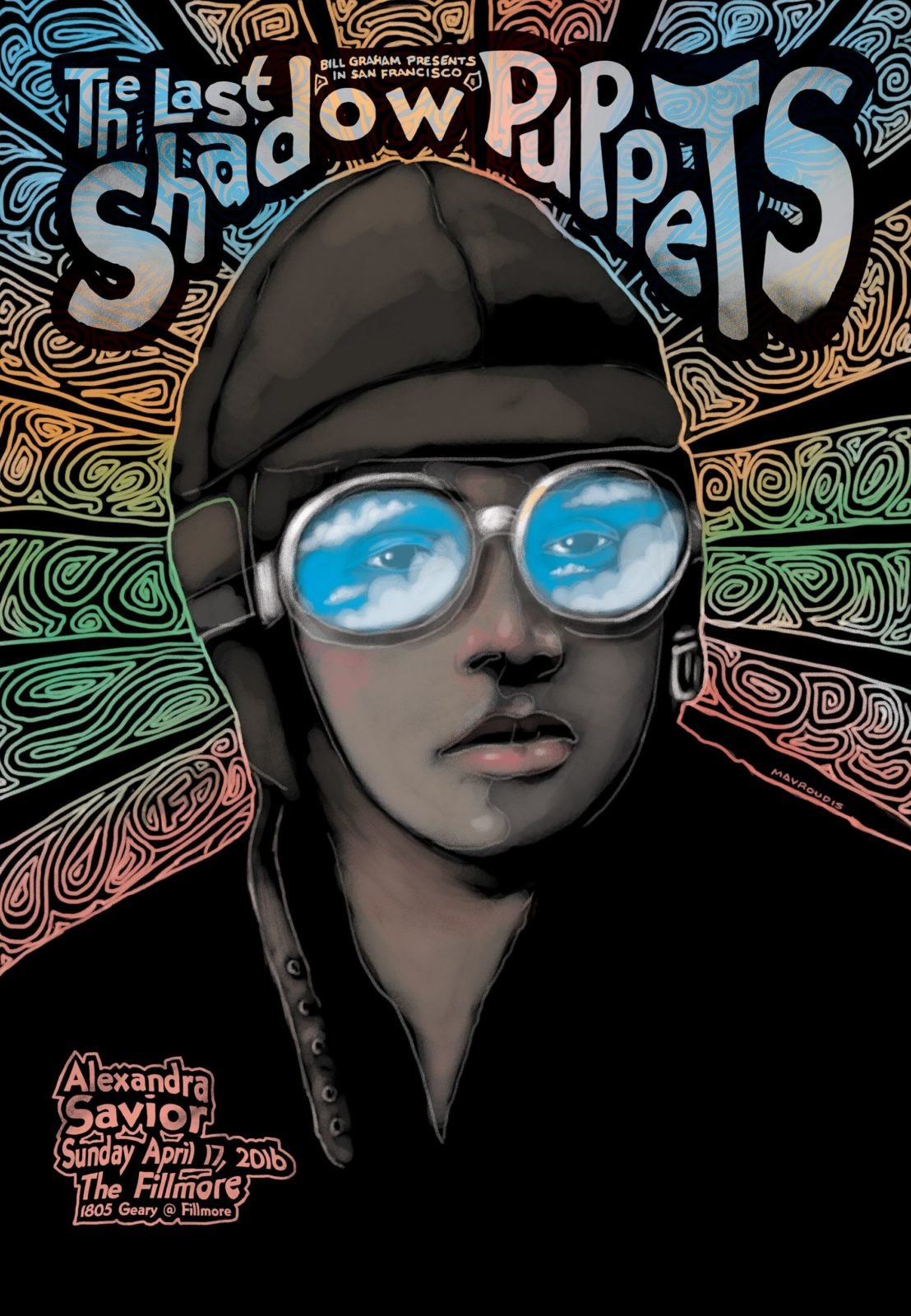

“In a lot of ways, what’s happening now probably mirrors a lot of what happened during the ’60s – there was a lot of turbulence and a lot of amazing art during those times. I think the same is happening now with journalism and writing and art. There is a lot of creativity and I think that art needs to be included in any resistance movement.”

Having said that, he is more prone to seeking consensus than confrontation.

“I have friends who are the opposite of me,” he says. “I have friends who voted for Trump and I think it is important not to completely eliminate yourself from the discussion. They are people I fundamentally disagree with on so many issues but I think the debate is important. I find it difficult, we argue all the time, and there are times that I want to pull the plug and say ‘what is the point of this? I’m banging my head against the wall.’ But some of these people I know since we were kids, we grew up together. When it comes to politics, it’s important to keep communication open, because at the end of the day, what are the alternatives? I don’t think any civil war is a pleasant thing. We owe it to everybody to keep dialogue open, to keep talking and hopefully see people prevail and work together to try to heal some of these rifts.

“I’m very political, I’m very stubborn but I also want to have my views challenged and be told when my views are wrong,” he says. “If I can’t intellectually or morally defend my views, then I have to rethink those views. It’s easy when you are sitting among people that all agree with each other; that’s where the problems start, because they start excusing things that they shouldn’t excuse. It’s good to have a little push back.”

So, when someone says that we live in an era in which Political Correctness has gone mad and puts restriction on artists’ freedom of speech?

“I haven’t really felt pressured,” he says. “I try to evaluate my art on my own but I don’t know if there is something that would keep me from submitting a piece that is worth saying. The people who complain about PC and say that we can’t say anything anymore, I usually question those people and I say ‘what is it exactly that which you want to say and can’t say now?’ More often than not it is something that is incredibly racist or sexist or homophobic. Are you upset because we are not giving you a platform to spew these views? If you just have an unpopular opinion and want to express it, I don’t think that anybody is taking your voice away. But I don’t like it when it’s an excuse so that they can get out their racist views – and it doesn’t mean they should be given the platform of the presidency of the US to express those views,” he adds, laughing.