On the tube travelling on the northern line to Sadler’s Wells, I grab a copy of the Evening Standard and spot a review full of praise for the opening night of stage director Dimitris Papaioannou’s latest production The Great Tamer, “wonderfully moving” is the finishing sentence. These are rare moments of pride for us Greeks in London, when one ‘of us’ manages to transcend our community and reach out to the metropolis. This is a particularly lucky week, with Yorgos Lanthimos’ latest film screening at the London Film Festival.

The director and choreographer’s work was not particularly known to the British audience. This is the second time he stages his work in the UK after Primal Matter in 2016, again under the Dance Umbrella international festival. The Great Tamer has already been staged in more than 20 cities around the world, some of them as far as Taiwan and Seoul. After London, the show will continue touring abroad in Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, the USA, Canada, and in February will head Down Under to the Perth Festival. Papaioannou will then return to Sadler’s Wells with Since She for the Tanzteatre Wuppertal Pina Bausch as the first choreographer to present his work with the group following Pina’s death in 2009.

Sadler’s Wells is considered to be the headquarters of European dance theatre; the meeting point for all creatives where new ideas sail to Europe and the world. Historically it is one of the two oldest theatre stages in London together with Royal Drury Lane, counting four centuries of continuous artistic presence since late the 17th century.

The contemporary studio has a capacity of 1,500 and tonight, for a second evening in a row, it is fully packed. The poster of the performance is decorated with the honorary ribbon that reads ‘sold out’.

I have managed to get a ticket for the second evening, offered to me by Papaioannou’s partners, only because Neos Kosmos had already booked the interview with him. I vaguely remembered from his previous work Dyo, which I had seen several years ago in Athens rather atmospheric scenes, frame by frame like paintings, coming to life and opening up their world to invite you in and allowing you to wander through.

I met with Papaioannou the following day in the lobby of his hotel. We had never met in Athens before 2004, when he was the talk of the town ahead of the Olympic Games, and when I was working for a magazine – “when there were still some magazines”, we laugh, though not without some bitterness for the sad turn of events in Greece.

Of course he is aware of that morning’s review – yet another positive one – of his show, published in The Times where among other things we read “Kudos to Dance Umbrella for presenting an intriguing duet by Papaioannou in 2016 and now, as part of the festival’s 40th anniversary, this large-scale work for 10 performers”.

“In Britain the audience does not usually greet the performers with a standing ovation,” I tell him, “unless they really like what they’ve just seen.” It’s true, after all, audiences in London are spoilt, used to watching performances of a very high standard.

“This is a real compliment for me,” he replies, modest, without exhibiting any signs of arrogance.

The Great Tamer reminded me of Alexander Pope’s words from The Dunciad: “Great Tamer of all, human art!” I took the book with me to discuss it with Dimitris. No, Papaioannou didn’t copy Pope. Pope copied Homer.

Maria Athini: Who is ‘The Great Tamer’?

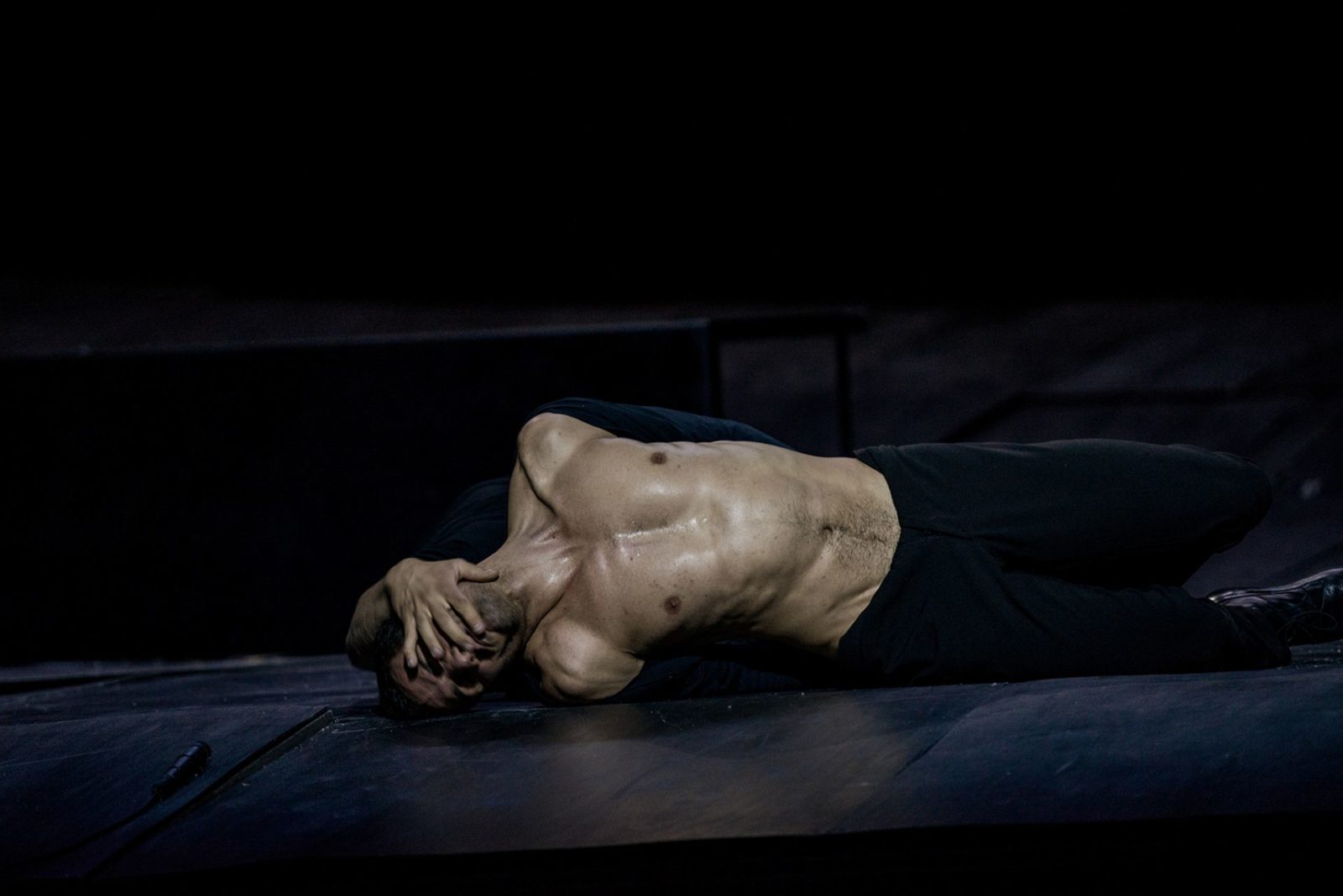

Dimitris Papaioannou: Homer refers to the ‘all tamer time’. My dear friend Angelos Mentis, who is the ‘godfather’ of all my plays, decided that we should name this play The Great Tamer and not The All Tamer as it bears many similarities to [a] circus. Indeed, the performance is about a great circus, the circus of our mind where time is the great tamer. The dancers are forming with their bodies creatures that can barely move or are flying over the stage. A woman with two men’s legs. Dismantled members, arms and legs moving on the stage, the body always at the epicentre. Naked or trapped like in the astronaut’s costume, heavily breathing or like the dancer with crotches, fully covered in plaster.

What is the meaning of all this?

It’s a mirroring, a reflection. Each viewer can take it as they will.

“The best thing about being Greek in the western world is that your heritage belongs to everyone. If you want to talk about archetypes, you will use the Greek myths. I don’t need to explain who is Antigone, Persephone, Narcissus or why I chose them.” – Dimitris Papaioannou

I noticed that the audience was quite puzzled.

For years, I felt comfortable with the Greek audience. But when we are playing in front of an international audience, I feel a new sense of enthusiasm because their sense of freedom rubs off on me. They feel free to walk out of the theatre, or stand up and scream out in joy. Honestly, I wouldn’t mind if someone were to walk out; I respect their opinion. I enjoy the dynamics of this interaction. The fact they feel puzzled after the performance is also very fulfilling for me.

The show is a sequence of scenes, poetic, allegoric, surrealistic, all from inside the all tamer, time. It comes in fragments, but there is a very strong link beneath the surface and a narration with extremely high aesthetics.

The pace is very slow, – a “zombie pace” as The Guardian wrote (another 5-star review) – and doesn’t change for the entire 100 minute performance. The music, based on the Blue Danube by Strauss, has been adapted by Stephanos Droussiotis and sounds like it is being played in the wrong tempo. There is no tension. Ever.

You never raise your tone. You don’t shock, you don’t provoke attention.

I know, I do it on purpose. I don’t want to steal any attention by making noise, I want my audience to come and find me.

What Papaioannou proposes is a dialogue in two stages. Stage one is happening at the moment we are viewing the scene. Stage two, is what follows afterwards in our thoughts and our feelings. Some scenes are taken directly from famous paintings like the ‘Anatomy Lesson’ by Rembrandt or ‘Narcissus’ by Salvador Dali where the dancer is watching his own reflection and splashing real water from a small lake.

After the show I overheard some conversations about poetry, painting, philosophy.

To communicate without words, I need to go back to our shared memories, the archetypes, the history of art. It’s a crack through which I try to sneak inside and speak without words. My topic is philosophical, existential. It’s the meaning of life, or what’s the fucking point?

In a review published in Le Monde newspaper, a journalist wondered “does someone have to be Greek to develop fragmentary art to such a degree?” What do you have to say to that?

The best thing about being Greek in the western world is that your heritage belongs to everyone. If you want to talk about archetypes, you will use the Greek myths. We are very lucky because this is our homeland. I don’t need to explain who is Antigone, Persephone, Narcissus or why I chose them. In my sense for Greekness, spirituality and sexuality are the same thing. It’s my thirst to redefine and reinvent beauty and harmony; what matters to me. Not deconstruction. One of the issues that I understand as coming from my Greek heritage is my obsession with dismembered bodies; the shard and its relation to the whole.

There were scenes, like when the female dancer was walking with men’s legs, where people were laughing.

That’s great! This is something you’d never find in Greece. People don’t laugh; they think ‘this is a serious performance we shouldn’t be laughing’. When you work abroad you realise that what we consider to be weird or funny makes others laugh as well. The wit encourages our childish imagination and opens up communication. What I’m saying to the audience is ‘Come on, let’s dream together’.

On a different note, what do you think about the situation in Greece? Are things getting any better?

I think we haven’t reached the bottom of the barrel yet. But there is a creative spirit starting to look out for alternative ways. Despair is now being transformed into common sense, saying ‘okay now let’s see what we can do with the means we have’. But I’m not the best person to speak about this because I travel so much and every time I return to Athens to my home and my friends it feels like paradise to me and I feel everything is getting better. The fact is that things are getting better for myself and other artists I know and respect for their work who were feeling trapped some years ago. We are all now working all around the world.

Do you sometimes feel like you are living outside of real life?

All the time. Next to this theatre, before our opening night, there was an incident, an attack and somebody got seriously injured and police cordoned off the area. I was passing by and couldn’t help thinking that my job is like somebody who is arranging flowers when the world around him is falling apart.

In the UK, the Arts Council is funding artists who apply for their projects, workshops, etc. Is this something you think Greek artists need?

The state funding scheme restarted recently and this is very good. Many groups, not ours obviously, have received funding for their projects. We are waiting to see the outcome of this opportunity.

Do you believe you have influenced other artists with your work?

It’s better to ask them! There have been more than two generations of dancers who have worked with me. If I helped them in any sense I would like them to say it themselves. More than anything else I want them to remember me as a collaborator and not as a mentor.

Would you teach you craft? Or is it too early to ask?

Even though I’m old enough now, I don’t feel I really have some sort of special technique that I can teach to others. I’m not so confident. What I can do, is lead people through a creative process; through this process I discover myself and I can share. But if you remove the target, which is the performance, I lose everything.

So we should be expecting more performances?

Some days I feel I’m only starting. It’s ridiculous, but this is how I feel. I’m bombarded by ideas and thoughts awaiting for the time to come out and at the same moment I’m empty and stressed about what to do next.

How do you overcome the fear of the blank page?

I know it is part of the game. It’s the carrot, the stick, everything that can put you back into the creative process. You have to work, there is no other way.

‘The Great Tamer’ will be staged at The Perth Festival from 8-12 February, 2019. Tickets from $36 – $75 + BF. To book, visit https://www.perthfestival.com.au/event/the-great-tamer