When contemporary witnesses speak of their experiences during the WW2 German invasion and occupation of Greece between 1941 and 1944, history comes alive. Before an online video archive of their voices could be made by historians of both countries a lot of persuasion work was needed because the resource was co-funded by the German government.

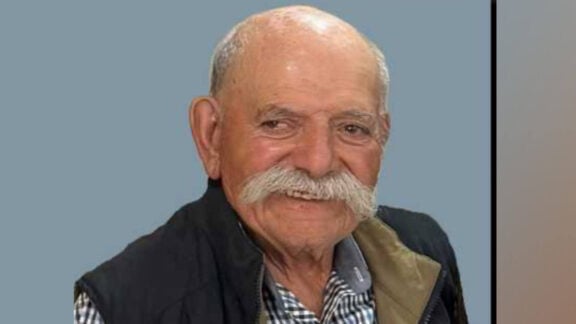

Efstathios Chaitidis survived because of a last altercation between his father and his yiayia (grandmother). When German troops came to his village Pyrgoi, his grandmother implored her father to leave the village because men were always shot first. But he wanted to take with him at least his wife and at least one boy of his five children. But grandmother didn’t want to let them go because she believed women would not be harmed. In the end the father agreed: “Then give me at least a boy.” And reached for Efstathios’ hand. Grandmother held on to his foot, but the father was stronger. Chaitidis recounts:

“We walked maybe a kilometre in a kind of gully. Then the Germans shot at us. And we ran and were saved. They took the rest of the family and everybody, the whole neighbourhood, into the village. The next day they locked them in a church and on the second day into four barns that they then set alight, [burning the people inside] alive.”

Chaitidis was eight years old. He has never forgotten the scenes of the massacre in his village, perpetrated in April 1944 on orders of SS colonel Karl Schümers as reprisal against partisan attacks. His father, who survived the occupation, was shot dead in 1947 as a “communist” in the Greek civil war. Chaitidis grew up orphaned. As did Argyris Sfountouris, who lost his parents aged four, when German troops went from house to house in his village Distomo shooting people one after another.

Distomo experienced one of the worst German crimes in Greece. The entire village was burnt down, killing 218 villagers. But Sfountouris also recounts that there were some saviours among the troops. “Many survived because one or two soldiers entered a house, shut the door behind them and shot into the air.”

Sfountouris and Chaitidis are two of 93 contemporary witnesses whose memories of the German savagery have been collated in a new online archive. The project was led by Professor Nicolas Apostolopoulos (nicolas.apostolopoulos@cedis.fu-berlin.de) at the Free University of Berlin. He attracted funding for it from various German government departments and from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation in Athens. On the Greek side the project is headed by dual German-Greek national Professor Hagen Fleischer (hagenfl@arch.uoa.gr) of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Apostolopoulos commented: “It’s interesting that the witnesses were quite keen to speak, but not to a German-funded project. It was rumoured that the Germans wanted to whitewash themselves by supporting it. Step by step we overcame that by lots of persuasion work.”

One of the main drivers of the idea was the premise that high schools in both countries are not teaching enough about the subject. The archive is to be made available to students in both countries in both languages. It’s also available to researchers. Apostolopolos hopes for lively interest, noting that especially in Germany much too little is known about its dark past in what is a very popular destination for German tourists.

To hear the testimonials go to https://archive.occupation-memories.org/de/searches/archive. More about the project, in English, German and Greek, is on the website of the Freie Universität: www.fu-berlin.de/en/presse/informationen/fup/2018/fup_18_073-online-archiv-zeitzeugen-griechenland/index.html

From the university website: “In the 1950s, the Federal Republic of Germany systematically downplayed all crimes committed during the Second World War. Massacres, reprisals and the brutal violence on the part of the German occupying forces were always twisted or relativized in favour of a bilateral renewal of diplomatic relations between the two countries, Greece and Germany, and both sides cultivated forgetfulness and collective amnesia. About the crimes of the German occupation in Greece there is public ignorance, even today. Oradour in France or Lidice in Czechoslovakia are places of horror and memory.

Kalavryta, Distomo and Klissura are, on the other hand, nonexistent in the map of European collective memory. One can read about Oradour in nearly all German textbooks, but for Distomo one can hardly find a single line in a school textbook.”

When the Nazi forces began retreating in October 1944 they left as rubble almost 800 villages and small towns. In the first winter of the occupation 100,000 people starved to death. 60,000 Greek Jews were deported and murdered. Almost 50,000 people were killed in the resistance and in reprisal massacres.

A persistent strain on relations between Greek and German governments remains Germany’s refusal to pay reparations for the damage it did to Greece. A Greek parliamentary commission in 2016 put the cost at more than 300 billion euros.

But there were also Greek collaborators with the Germans. Stratos Dordanas, assistant professor for modern and contemporary European and Balkan history at the University of Macedonia, explained in a TV interview how a long taboo and still controversial topic in Greece is now open to debate.

“Today we are certain that many Greeks collaborated with German troops and the SS during the war, and for many different reasons. For some, taking up arms was a new adventure, as was adopting Nazi ideology. Connected to that was the chance to earn money as public officials, or to benefit from the distribution of war spoils or wealth that had been appropriated from Jews.

Some people also hoped to increase their survival chances under the difficult conditions of the occupation. And others still saw collaboration as the only way to protect their families and villages from the attacks of resistance fighters.”