In a recent press release, Amnesty International called for increased restrictions on police use of electricity-conducting weapons (or ‘tasers’ as they have become widely known). Amnesty noted that “the known death toll from tasers” has risen to 500 in the USA since 2001.

Taser International, developers of the technology, have responded that “only 60 deaths have a direct causal connection to taser use, and the rest are simply taser-related”. All in all, taser argues, the weapons have saved many thousands of lives, where police might otherwise have had to use lethal force to subdue subjects. There’s broad consensus that the technology, when employed with discretion by trained police, can save lives, where the alternative would have been to use a firearm to immobilise a dangerous person.

The problem seems to lie in the ‘discretionary’ part – specifically around the area of police restraint. Controversy has arisen here in Australia, over cases of excessive force in the deployment of taser technology resulting in deaths and severe injuries. As a consequence, the Australian Federal Police and the States of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania have limited the use of the weapons to specialist branches of law enforcement. The rest of the States continue to allow general duties police officers to employ the technology under the relevant police guidelines. Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission research and evaluation director Rebecca Denning told the Courier Mail in November 2011 that “40 per cent of all subjects who had a taser deployed against them were the subject of either a multiple or a prolonged discharge”.

Further, Denning said, “four per cent of subjects of taser deployment were suspected of having a physical health condition, 17 per cent of having a mental health condition and just under 80 per cent of being under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol.” A quick review shows that this technology is being adopted all over the world in law enforcement, with varying degrees of regulation.

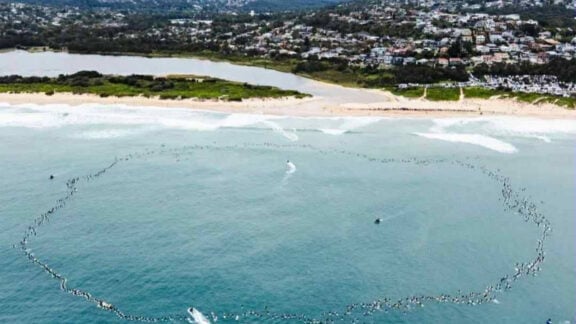

Recently, UZI has developed a riot shield with the technology built in, and taser a scalable, stand-alone multiple delivery system called ‘Shockwave’, presumably designed for ‘non-lethal’ crowd control. It is broadly agreed by police unions and associations worldwide that the use of this technology should be better regulated, and clearer policies developed, to protect the interests of both citizens and police officers, but meanwhile the technology will no doubt be rolled out. Now, as police in cities across the globe are increasingly seen to be using disproportionate force to disperse huge crowds of peaceful protesters, it’s disquietingly easy to imagine giant banks of tasers lined up and pointed at the public square, able to zap a whole crowd into effective paralysis simultaneously.

We have seen too much state brutality lately to imagine this might never happen. Of course, to those mindful of events in places like Syria and Bahrain, where citizens are being shot in the streets, discussing the dangers of excessive force with tasers might seem irrelevant. The regimes concerned aren’t interested in dispersing crowds – or in non-lethality, it seems. But here also we must consider the United Nations Committee Against Torture’s concerns that these kinds of weapons are being used to inflict severe pain and death behind the closed doors of state. Electric shock has been a preferred instrument of torture pretty much since electricity was invented, so it’s not surprising.

In Greek mythology, the power of lightning was the realm only of Zeus, King of the Gods, Lord of Law and Order, the Great Male Sky God of Power. Out of nowhere, Zeus could zap a wrongdoer with a huge bolt of his magisterial electricity, and that was that. He had spoken. Zeus permitted none of the Immortals to use his deadly lightning bolts, except for his daughter Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and Warcraft. She, with clear strategic eyes and infinite intellect, could be trusted to respect their destructive as well as tactical power.

The Titan Prometheus stole a spark of fire from Zeus’ lightning bolt, hiding the ember inside a stalk of fennel and sharing it illicitly with his poor creations, the mortals. When Zeus discovered this, he raged that humans were incapable of handling such a powerful force, as we were foolish, rash, brutish and unworthy. (Prometheus was severely punished for this transgression, but that’s another story.) The lightning bolts of Zeus, the primeval power of directed electricity, belonged to the Great Sky God, his wise daughter Athena, and to them alone. Not anymore.

We have entrusted our police officers with this power, in the hope that the state contract with its citizens will be honoured and lives might be saved in the maintenance of law and order. Now, as new crowd-control adaptations arise quickly, there is fear that technology might overtake the law, in future clashes between protesters and the establishment. Police officers represent the law and are tasked to enforce order, but they are mortals nonetheless. Perhaps Zeus was right about us? Are we too foolish, rash, brutish and unworthy to wield his weapons, simply because we are human?

* Joanne Lock is an independent writer based in Australia. She studied political science and international relations at the University of Queensland. To contact Joanne or to read more of her work, please visit www.joannelock.com