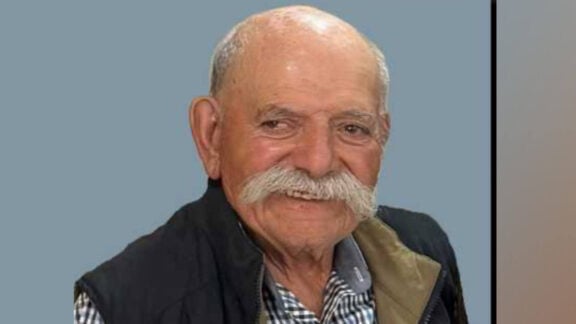

Having made a name for himself as a film editor, mostly working in the UK (where he also did trailers for Warner, most notably for Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut and Clint Eastwood’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, Yannis Sakaridis is now one of the most acclaimed directors of the current new school of Greek cinema.

In spite of the political and economic situation in the country, I believe that Athens is a significant cultural centre for Europe and a field of inspiration for the arts. There is a talented, brilliant generation of creators making films in Greece, excellent actors in theatre become better and better every year and it is only a matter of inspiration and script for something great to start

His filmography includes many short films, but it is his first feature film, the political drama Wild Duck that made waves around the world, in the film festival circuit.

His second feature Amerika Square a depiction of life in economic-and-refugee-crisis stricken Athens, is already following the same route, featuring in film festivals around the world, from Istanbul to Chicago, the final destination being Hollywood, as it is Greece’s official submission for the Foreign Language Oscars. The film is also featuring in the program of the Greek Film Festival, which is a great opportunity for a discussion with the director.

How did Amerika Square come to be?

The first draft of the script was written by myself and Vaggelis Mourikis; we did a short film together in 2006, called Truth which was shot in the same area and was about a coffeshop owner who gets motivated to fight an oil company.

So Amerika Square started by Mourikis, who grew up in the area and myself, coming back after 18 years in London, and to discover both the cultural past of the square and its current multicultural character.

We wanted to talk about racism and the refugee crisis from the viewpoint of someone who has lived abroad for years, Vaggelis in Australia and myself in the UK.

While the crisis went on, we found ourselves unable to make the film.

In the meantime, the square kept changing. When we were able to start production, it was 2015 and the square is in the centre of the crisis. It is a modern-day Casablanca, where many refugees wait for their ‘ticket’ out. Billy’s character changed and became a tattoo artist (played by Yannis Stankoglou) who falls in love with a trafficking victim from Africa (Ksenia Dana); another storyline follows a Syrian doctor (Vassilis Koukalani) who is trying to go to Germany. Much of it is based on Yannis Tsirbas’ novel Victoria Does Not Exist, which features a banal racist, Nakos (Makis Papadimitriou).

Tsirbas has a unique way of describing the residents of an apartment building in which the three main characters meet.

He keeps a fine balance between humour and Nakos’ racism and I think he is clear in making a point.

How did you pick the cast?

I do the casting before the script is finalised, so we discuss the subject and the characters with the actors, who are encouraged to include personal elements and insight to the script – their life, dreams, what they imagine and what they want to do.

It’s an avant-garde autobiography. The script is an organic process, developing until shooting starts. We do a few rehearsals and when shooting starts, there is room for freedom in dialogue and motion; freedom to improvise. This is done with a sense of complete trust towards the actors, which is true; they feel that I trust them completely and this feeling comes out in the film.

How would you describe Billy’s relationship with Nakos?

Nakos is a racist; Billy, on the other hand, falls in love with an African girl, for whom he is ready to risk his life. Nakos and Billy grew up in the same apartment building, they went to school together and are friends. You are not born racist, you become racist and in this case we have two people coming from the same economic, social and educational background who take opposing sides towards the refugee crisis.

Nakos is a textbook case of the ‘banality of evil’; how an everyday person can become able for the worst. How real is this character?

He’s all too real. We all have a friend we went to school with and hung out together and one day we run into him on the street – or on Facebook – and ask ourselves, as Billly does: “When did you become like this?”

As a director, I avoid melodrama when it comes to issues which are by nature dramatic and I try to deal with ‘villains’ with tenderness and love, discover all their sides, their humour, sarcasm, their ‘good’ side. I’m looking for a form which will be close to a new neorealism, with humour, lyricism, fast-paced narration and density of subject.

There is no mention of the financial crisis in the film, despite its shadow being cast all over the place. What does the crisis mean to you and your work?

In spite of the political and economic situation in the country, I believe that Athens is a significant cultural centre for Europe and a field of inspiration for the arts. There is a talented, brilliant generation of creators making films in Greece, excellent actors in theatre become better and better every year and it is only a matter of inspiration and script for something great to start.

What is the significance of tattoos in the film?

A tattoo is the only personal item that can be safeguarded by someone leaving their home in Africa or Asia to travel under adverse conditions towards Europe or Australia. Furthermore, a tattoo is the same in every skin colour, every race. ‘Refuse to sink’ is the most popular and common tattoo among refugees travelling by boat. It is the tattoo shared by Billy and his friend Teresa. ‘Refuse to sink’ is also a good motto to live by: keeping on making cinema and dealing with the crisis. In the words of Billy: “Even ink, the humble ink, lasts longer than us, longer than our loves, our sweat, our body even. A year and a half, it takes a year and a half for a tattoo to disappear, after you die…”

Greek cinema is blooming, lately. Do you think there is a new school of Greek filmmakers?

Yes, this is clear to me; there is a current and contemporary Greek cinema which is definitely political. For me it all started with Constantine Yannaris and his film From The Edge Of The City. It is a seminal film, marking the beginning of a new era for cinema in Greece.

What does ‘Greek cinema’ mean today?

Cinema is a universal spiritual experience, unique and capable to open new ways for discovery – outwards, but mostly inwards.

Amerika Square is Greece’s official submission for the Academy Awards. What does this mean to you?

Responsibility, heaps of work and a chance for distinction.

* ‘Amerika Square’ screens in Melbourne at Palace Cinema Como on Friday 13 October, and in Sydney on Friday 13 and Saturday 21 October at Palace Norton Street. For more info visit greekfilmfestival.com.au