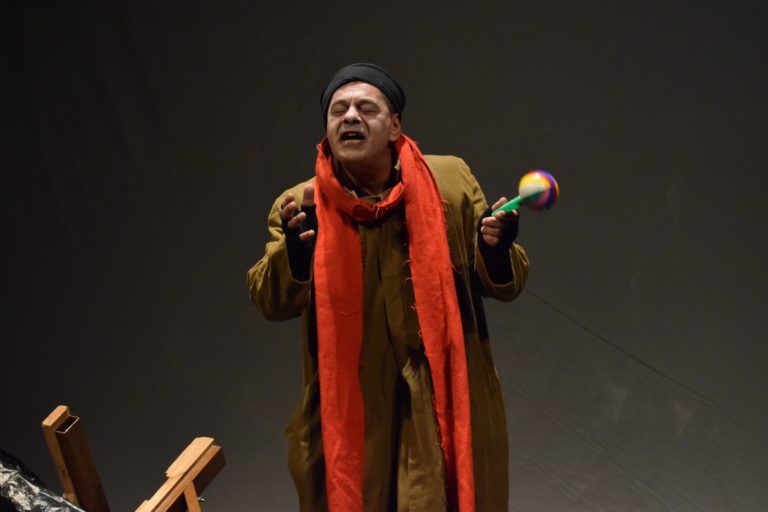

Up until a few years ago, Christoforos was a typical middle-class Greek, a small business owner who, due to the crisis – and after a series of personal unfortunate events, not least of them his wife’s demise – ended up losing everything and living on the streets, a homeless person. Having been used to decorating a Christmas tree each year, he decided to do the same on the street. He found one and started decorating it with things he found in the rubbish, symbols of the long-gone days of plenty. But the tree was too big for him, so he ended up placing it sideways, and in the end it looked more like an epitaph, than a Christmas tree.

For the past three years, Christoforos has also been the alter ego of actor Nikos Magdalinos. Because Christoforos is not a real person. He is a fictional hero, the sole character in Giorgos Maniotis play ‘To Dentro’ (‘The Tree’), which is presented these days at The Greek Centre for Contemporary Culture, after a successful run in Athens and a tour around Greece.

In fact, this is the first stop of what Nikos Magdalinos aspires to turn into a long tour in Greek Diaspora centres, hopefully under the auspices of the Greek deputy ministry of Agriculture.

“I went to the Deputy Minister, Vasilis Kokalis, who is very approachable and suggested that I should take along promotional material from small, family-owned businesses, so that we could have a stand in each venue, where we showcase Greek produce,” he explains, expressing his interest in including similar ventures from small businesses of the Diaspora. “This is how Greece managed to survive, with the help from the diaspora,” he says.

“This is not the first time that Greece has defaulted, it is the third. We will rise again. But we need to be united. There are ten million of us in Greece and even more all over the world.”

Nikos Magdalinos speaks of personal experience, having been a part of the Greek Diaspora himself.

“They took me from the playground when I was five and up until I was 17, I still hadn’t got over this sense of bitterness, being stranded behind this big, heavy, wooden door in Frankfurt, Germany, rain pouring outside, and knowing that back in my village, Lidia in Kavala, my friends are all outside playing in the sun,” he remembers.

“My parents may have missed the best years of their lives, but they gained other things and they have raised us to be responsible and dignified. Germany taught me discipline, something that has helped me a lot in my work, and this is why, I have never been out of work, in my 33 years in theatre – most of which I spent in the Greek National Theatre and the State Theatre of Northern Greece.”

However long and fruitful his career may have been so far, this latest role is the most important of his life. “It is a great honour for me to have been chosen by Giorgos Maniotis – the last of the great Greek writers – to play this extremely difficult part. I spent three months alone at home, studying the part, immersed in this man’s life.”

Most actors, when on stage, look for support from one another, but himself, being alone on stage, admits that he only has the character to rely on.

“I step on his passions, because to me he’s like Christ.”

This experience has also affected the way he looks at homeless people, who “have a unique sense of time”, because, as he says, “the way things are now, nobody knows if tomorrow it’s their turn to be on the streets.”

This is why he thinks that Christoforos is not one person, but a symbol for a lot of people. “You sense that he is a person aloe, balancing on a rotten board at sea, looking for land,” he says.

“He’s decorating that tree because he has been told that it is a symbol of joy and prosperity and it is something that he had been doing with his family and doesn’t want to let go. The ornaments are stuff he found in the rubbish, things that used to be symbols of prosperity but are now useless, because there is no prosperity.”

For the actor, this staging in Melbourne is extremely significant, given that the local Greek community is becoming larger, infused with the newly arrived migrants from Greece. “The biggest victims of the crisis are here,” he says.

“These are people whose sense of dignity led them to leave the country, in order to be able to raise their families. They may have rescued themselves, but nobody knows what they have left behind and how they’re handling it, psychologically. This play is about them, it was written with them in mind.”

It is to them, as well as to the broader community, that the main message of the play is addressed: “The main theme of the play is to banish guilt,” he explains.

“We need to stop thinking that we are guilty of the country’s collapse. We are not. It is one thing to vote for people who led the country to ruins, but no, we were not in this together, we did not sit at the same table, we were not partying together at clubs, most of us were decent families, working hard who ended up on the street. They are trying to coerce us into accepting guilt, into becoming their accomplishes by force. I don’t know anyone in my environment, no relative, nor friend, who has been a rorter. We hear a lot of stories, about a lot of people, but nobody gets punished and we end up paying the bill for their actions. This is the canvas on which people have taken their own lives, souls have languished, there’s a depression looming in the air, and nobody knows if it go away or where it will lead.”

He’s not optimistic.

“I think that the hardest times are just starting,” he says.

“This is where things will go downhill from. Because the vultures are waiting for the full destruction of the country, its complete impoverishment, before they sit on us and start feasting.”

‘To Dentro’ will be presented – in Greek – at the Greek Centre for Contemporary Culture (168 Lonsdale Street) from Thursday 8 to Sunday 11 March. For showtimes and tickets, go to https://www.trybooking.com/book/event?eid=344757&