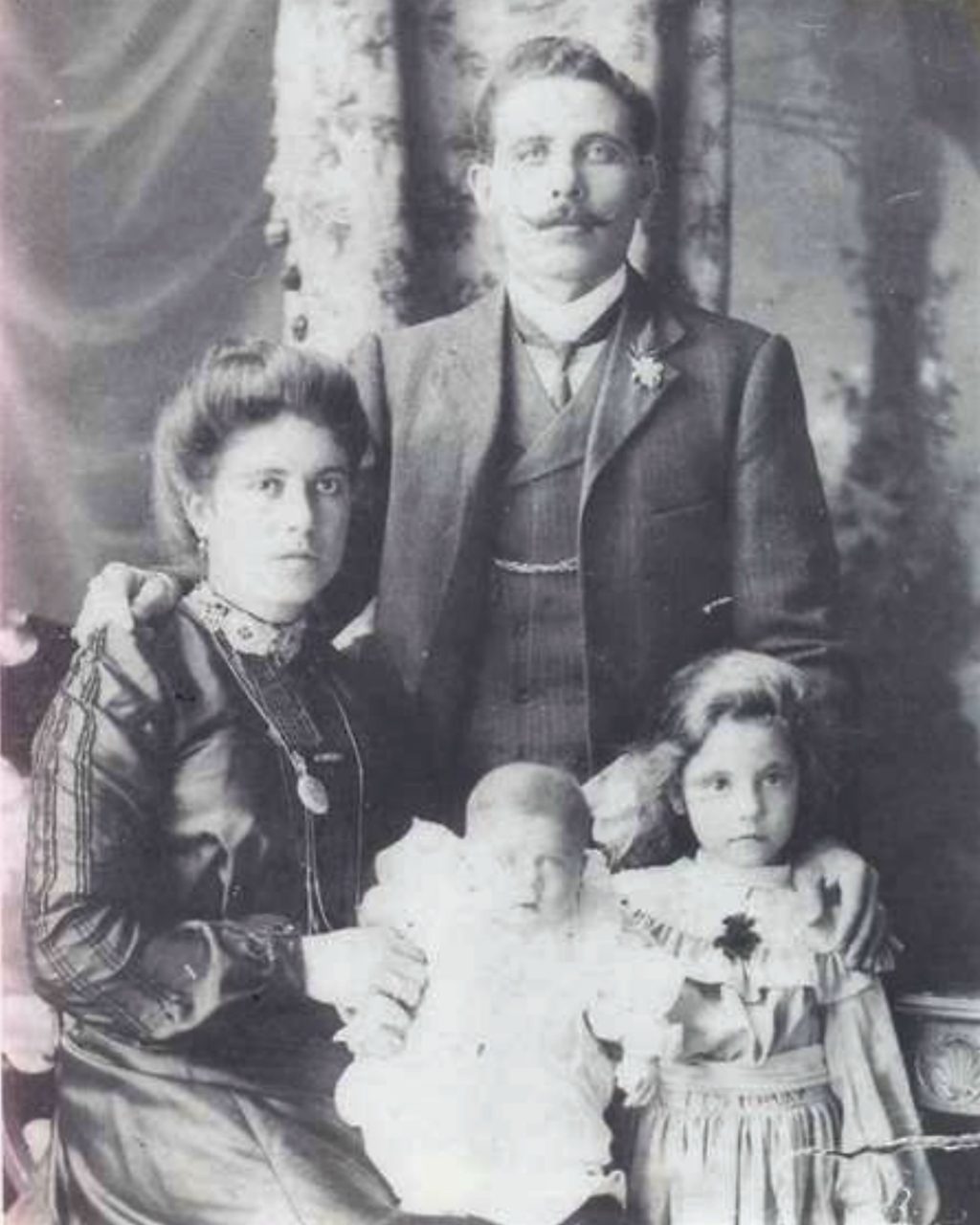

Young but courageous, helpless but determined to succeed, the first Greek migrants who arrived in Australia in the early 1900s, seeking a better future for themselves and their families, are without a doubt the real heroes of the diaspora.

While most Greek migration to Australia is associated with the period immediately following World War II, in the early 1900s chain-migration patterns began resulting in large numbers of arrivals, mainly from the islands of Kythera, Ithaca and Kastellorizo.

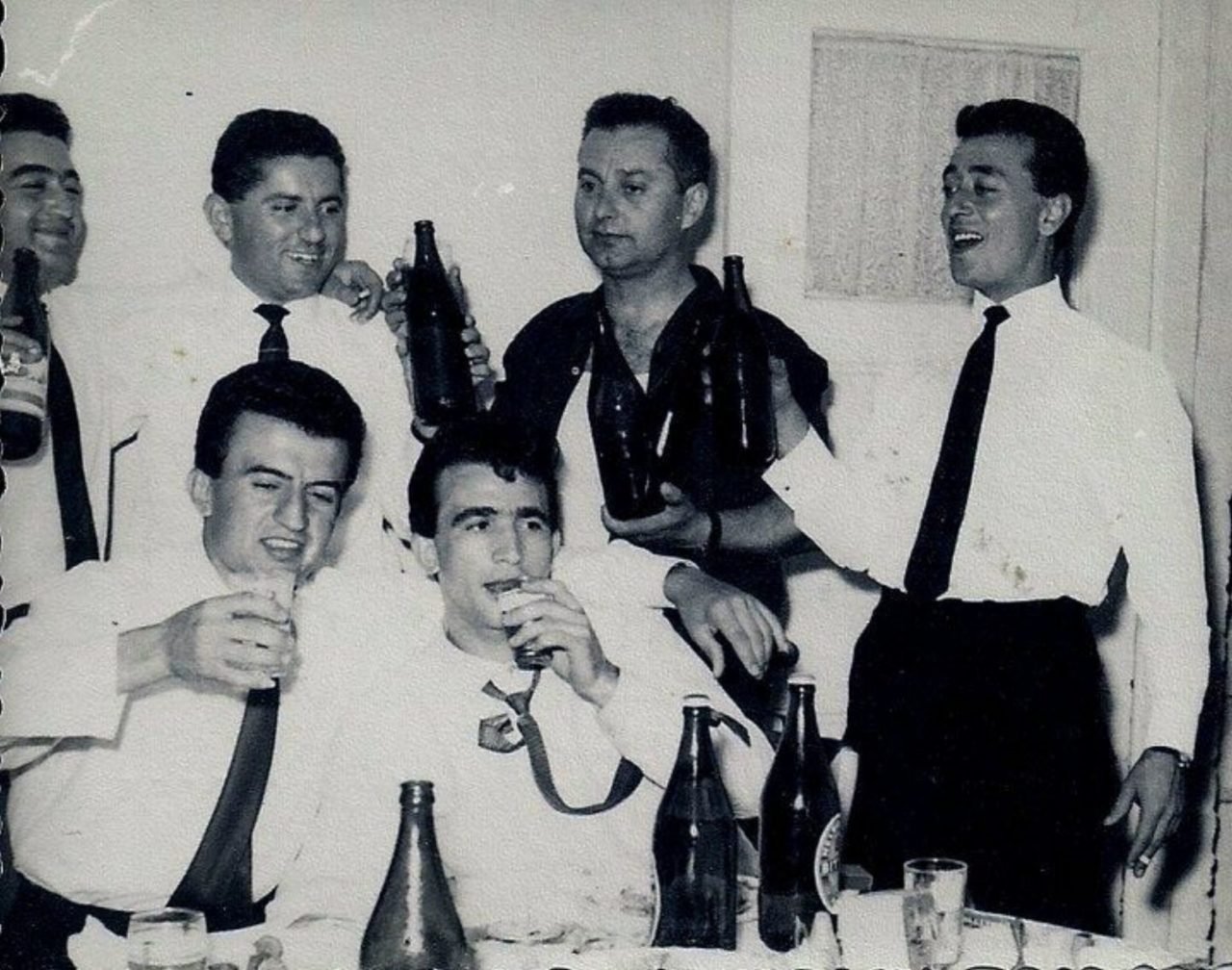

Predominantly male, the Greeks arrived in Australia and worked hard in fruit farms, factories and mines in order to make a better life for themselves.

According to testimonies, upon arrival in the land of opportunity, the young adventurers were greeted with suspicion and fear by the residents of a country that was already trying to overcome its own anti-migration hysteria, nevertheless, they worked hard and by the end of the 19th century the Greek communities of Sydney and Melbourne were well established.

Once settled, the first Hellenes began to shape their own little communities, build their own enterprises and establish partnerships that led them to be pioneers in many industries around the country.

After World War II, the Australian need for labour rises steeply. From 1947 up until the early 1980s, the country sees approximately 250,000 Greeks entering Australia, as a solution to problems of unskilled labour shortage and population growth.

Greek migrants arrive once again in Australia and spend months on end in migration camps waiting to be given the opportunity to work and prove their worth.

“Despite the unfavourable conditions that they came across, those Greek immigrants of the first generation held their heads up high, stayed united and managed to prove their worth and gain the respect of the members of their Anglo-Saxon communities. They worked hard and added value in all industries they were involved in and were always mindful of extending a helping hand to their fellow Greeks,” says President of Cypriot Aged and Pensioners Association of S.A. Inc, Christos Ioannou, pointing out that it is now the following generations’ duty to speak up, share their grandparents’ and parents’ stories and ultimately honour their ancestors, who worked extremely hard in order to establish themselves in Australia in such positive and constructive ways, carving the way for the generations that followed.

“When I first arrived in Australia, I did not like anything about it,” he adds.

“I remember the first three years of living here, I was trying to convince myself that I would eventually make my way back home. I have now spent over half a century in ξενιτιά and I can honestly say that the one thing that kept me going, helped me assimilate and make a better life for myself and my family in Australia, was the fact that those first Greeks had put so many systems in place for me, and all of us, to still make me feel at home even away from home.”

Despite the endless difficulties and the hardships that they encountered along the way, the men and women of that era never forgot where they came from and were always mindful and keen to preserve and promote their own cultural identity.

They kept the Greek language alive, they kept traditions and customs alive, they built churches, cultural clubs, educational centres and ultimately promoted Hellenism in a multicultural society such as Australia.

“I have so much respect and admiration for all migrants of that era,” says 54-year-old Greek Australian entrepreneur George Papadopoulos.

“Our parents were the real heroes. They didn’t speak a word of English, they worked hard, they received no support, they had no family, nor money, yet they made a life in a foreign country, and instilled in us some incredible family values and work ethic that is permanently embedded in our DNA,” he adds.

Greek Australian women also made a significant contribution, beyond the factories and beyond families.

They were involved in the community, schools, literature and the arts, politics, unions and across various professions.

Despite all this, a significant number of members of Greek communities around Australia insist that the work and contribution of these first-generation Greeks in Australia has yet to be recognised.

“I believe that we still have a long way to go,” says first Greek Australian actress Chantal Contouri.

“The first migrants have offered a lot to this country and also Greece and we certainly need to look at ways we could highlight their sacrifices and hard work and honour them in a way they deserve to be honoured, whether that involves a unified and Australia-wide cultural centre or even by establishing a statue of the Greek migrant back in Greece recognising the significant financial contributions Greek Australians made to their birth country,” she adds.

Forming a united body Australia-wide could make Hellenism in Australia reach even higher levels of excellence, marking a bright and momentous chapter in the pages of Australia’s migration history book, argues Mr Ioannou. “We did it once, we can certainly do it again,” he concludes.