There’s a Greek saying that goes Θα γίνει της Κορέας that roughly translates to “All hell will break loose”. The expression gained popularity in the ’50s upon the return of servicemen of the Greek Expeditionary Force in Korea, and it’s an idiom that Konstantinos Kontossis has felt under his skin.

He tells Neos Kosmos that his time in Korea was just a small pit stop in a life filled with both struggles and joys, but the hallway of his Burwood home in Melbourne tells another story. Filled with medals for valour, war memorabilia and certificates of appreciation, it is obvious that his time as a soldier was life-changing. As we talk, the 90-year-old’s eyes flicker to the time when he was a 19-year-old boy just after World War II had ended, when Greece was in tatters and trying to rebuild itself following the Nazi Occupation.

Mr Kontossis tells of the fear he had felt when a German soldier had pointed his rifle at him. But he had survived and it seemed the worst was over when he appeared for his compulsory conscription service in 1951. He was taken to Veria to serve under a high-ranking officer and family acquaintance, Ilias Liarakos, that he had known beforehand from his uncle, brigadier Anastasios Kontossis. There, the young conscript, and another 59 men were told that they would be sent to the battlefields of Korea to fight the Chinese and North Koreans for the liberation of the South. In unison, all 60 of them said “No!”.

Growing up in a poor family in Larissa, Thessaly, Mr Kontossis had yet to even venture to Thessaloniki, let alone know anything about Korea – and the idea of giving up his life for another country’s freedom seemed a futile cause to die for. But Mr Liarakos insisted that it was their duty to heed the call of their country and join in the United Nations’ appeal for assistance.

READ MORE: Modern war veteran Ken Tsirigotis decided to be a soldier, aged 13, at Syntagma Square

The men were given 48-hours leave to bid farewell to their families. Mr Kontossis’ father swung into action and they went to visit their brigadier uncle, who had retired in Athens. Over Greek salad and fine wine they were told that nothing could be done to revoke the decision. As they were leaving, his uncle patted him on the back and said: “Kostas, don’t be afraid! You’ll be fine. But all I want from you is this – if you’re ever in danger, it is better for you to die rather than be caught as a hostage”.

Mr Kontossis said that this advice was always on his mind as he had heard what inhumane torture hostages were subjected to by the Chinese, such as nail pulling and other techniques.

“I was determined that I would die instead of being caught,” he said, adding that there are things worse than death.

Once in Korea, he served in the front line for two months, in what was known as the “Death Division”. He would be awake for most of the night, sleeping only a couple of hours, with missiles falling everywhere. Fragments from a missile struck his eye, and he was rushed by jeep to the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH), where he was patched up by American soldiers, transported to Seoul and then put on a flight to Japan with other injured parties – some of them chained up, suffering from mental illness, with one of them escaping and trying to jump out of the plane that wavered in the air.

Tokyo hospital was a fun place to be, filled with visitors, entertainment to boost morale and plenty of laughter.

“I couldn’t understand a word of what they were saying but they would mime sketches and entertain us,” Mr Kontossis said. “In the last week I was there, a man came and took me to Yokohama on a rickshaw where I went on a shopping spree of goods that were sent to Greece.” These would later fetch a good price, and even contributed to his sister’s dowry.

After his brief recuperation he was sent to a US camp along with another two Greeks that had been in hospital with him.

“The American soldiers were well-trained and kept making us do exercises, but we couldn’t understand them,” Mr Kontossis said. “They kept saying ‘left, right, left, right’. And we did not want to do exercises with them.”

Mr Kontossis may not have wanted to fight in the Korean War, but by this stage he was invested in it and the idea of doing exercises with American soldiers rather than fighting side-by-side with his countrymen was distressing.

“I went to the major and said, ‘Major, our country sent us here to fight in Korea, not to come for exercises with Americans in Japan. Send us back now,'” he had said. That night, all three Greeks were back on a ferry to Indonesia, before secretly travelling to Korea. By now, the fighting was in the mountains, and Mr Kontossis could see the Chinese rushing up towards them like ants.

READ MORE: The Greek Anzacs who fought for their new country

Greek soldiers in Seoul.

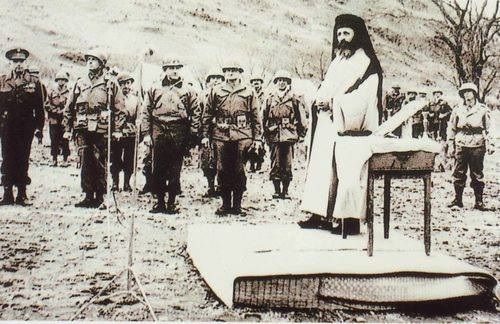

Archimandrite Hariton Symeonidis at a Holy Water blessing on the war front.

“They ran like crazy because they were doped up. We kept killing them and the ones at the back would stomp over their bodies and rush forward as though they were going to a party, not a war,” Mr Kontossis said.

His division kept moving because of the stench of the dead bodies.

“In winter we wore white to camouflage ourselves as we trudged through the snow. We’d travel through the countryside, crossing rope bridges that made you feel that you were walking mid-air,” Mr Kontossis said. “We were often very thirsty and hungry. An airplane once threw a package filled with donuts, but our lieutenant kicked it off a cliff because eating the sweet donuts would have made us thirstier and we could have died. We would find moist roots to wet our lips a little and move on.”

The tiredness and hunger sometimes caused friction. As for camaraderie and mateship, Mr Kontossis said that everyone was too focused on staying alive to buddy up like they do in American war movies.

He survived by detaching from his surroundings, but as he tells his story there are moments where he chokes back a few tears. He remembers Christos and Yiannis, corporals from Evia.

“We were divided into groups and these two fellow Evians were split up. I asked Yiannis if he wanted to swap places with me to be in the group with Christos and he jumped at the chance,” Mr Kontossis said.

At one point the division with the two Evians had been attacked and Mr Kontossis was sent with other men to bring back the bodies. As he moved through the naked, burnt earth, he saw Yiannis lying dead with a missile having cut through half his face, half his tongue dangling from his mouth, wounds raw and fleshy. “God forgive me,” he said. “He came for me. Further down was Christos.”

Mr Konstantinos Kontossis stands in his hallway filled with framed certificates of appreciation and bravery awards.

Korean war veteran Konstantinos Kontossis and his wife look over clippings saved over the years regarding the Korean War.

Then there was that time when he stumbled upon an injured Chinese soldier hiding in tall grass.

“He immediately lifted his arms to surrender. We turned him over and took his rifle, knife and grenade. He also had a little bag of boiled rice ready to eat, and another bag of hashish,” Mr Kontossis said.

“I cleaned his wound, put some medicine and bandaged his leg. After he ate his food we struggled with him up the mountain, injured, step by step only to be told to kill him.

“Yes, I remember Skatsas asking, ‘Why did you bring him here? What are we supposed to do with him? Kill him.’ But we could not, so he got one of his other men to do that.

“In war you either kill or are killed,” Mr Kontossis said.

He returned to Greece in 1953, but he did not feel like a hero at all. In retrospect, he is glad he was sent to Korea, though he initially did not want to go.

“Countries need the help of other countries so that justice can be served, so that the people can be free,” he said.

He is happy to see how Korea has thrived and when he meets Koreans he likes to introduce himself and talk about their country.

But for most people, it is known as ‘The Forgotten War’, or at least the exploits of the Greek Forces who fought there are only vaguely remembered. For the sake of posterity, Mr Kontossis has written a 160-page manuscript that sits unpublished in his drawer … a legacy for his progeny along with the medals.

As a veteran, he proudly marches every Anzac Day but he feels that this year may be his last.

“I am 90 and the walk is harder for me to do every year,” he said.

This year, he will receive a 50-year certificate for his membership with the RSL. Despite the honours by the Greek and Australian governments, he wishes he had a Gold Card like other Australian veterans that fought in Korea.

“They won’t give me one because even though I fought on the same side, metres away from Australians, battling with a common enemy, as a Greek citizen I don’t get any benefits from Australia, Greece or Korea even.”

All he gets, is the title of ‘hero’, which he refutes.

“No,” he said, “I’m not a hero.”