As a teenager, Fiona Strintzos remembers walking to Lonsdale Street to visit her dad at his restaurants because, as she says, “he lived at Lonsdale Street and only came home for five hours to sleep”.

After school, she’d saunter from Mac.Robertson Girl’s High School to Xenia restaurant at a time when the Greek Precinct was at its zenith. She’d pass by Salapatas and his mixed business, Pitsilidis’ deli, Karras’ music store, Papadomanolaki who had Minoa Vaftistika, Medallion coffee shop, Kypseli restaurant where Tsindos now stands, and would walk by Greek travel agents Kyriakopoulos and Pervolianakis.

“I knew them all,” she recalls, saddened by the fact that the robust Greek precinct has for years had its Greek character slowly etched away.

For Fiona, it’s also a personal hurt, because pioneers like her parents Michael and Cleo Nikakis were amongst those whose legacy lies in Lonsdale Street.

The community’s heyday

Back in her childhood, however, Fiona took the Greek precinct for granted. Even she gets confused when trying to keep track of her dad’s Greek venues like Grinos, Xenia and many more, including the Hellas Club and Panorama, famous for its wedding receptions and community dances, on the second and third floors of the old Greek Centre (168 Lonsdale Street).

READ MORE: History matters: Lonsdale Akropolis Club bombing of 1928

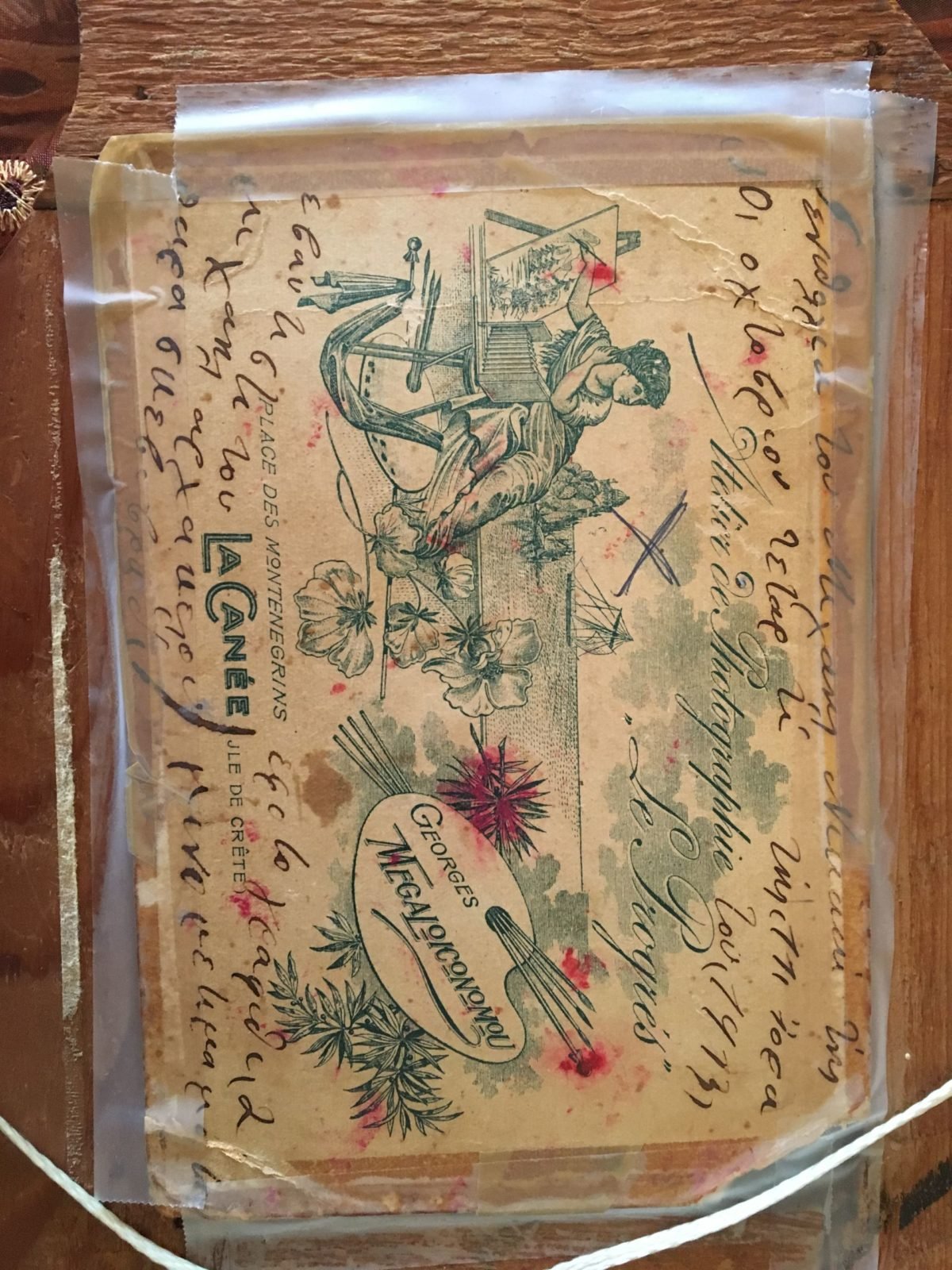

Frame created by Michael Nikakis while in prison. Photo: NK

“My parents’ main clientele at Hellas Club were all the Greeks of Lonsdale street, especially men who came during the mass migration,” Fiona tells Neos Kosmos. “They were men without families, and they had nowhere to eat.”

Her father, Michael, born in 1913, could put himself in the shoes of his male-dominated clientele as he, too, had come to Melbourne from Chania a single man in 1938. Unlike other men who came to make their fortune, Michael left behind a comfortable life in Crete where the family tannery ensured their providence. It was his leftist ideology which got him into trouble, however. “He even went to prison at Souda,” Fiona says, showing us a delicate frame he created to bide away the time before he left the political strife behind him.

“He came on a cargo boat and stayed with my great uncle George Nikakis, pappou’s brother,” Fiona said, remembering George, the owner of the Centenary Hotel on Lonsdale Street where more and more Greeks would rent out rooms drawn by their countrymen already there.

Slowly a Greek precinct began to be etched out in the area.

Michael with Mikis Theodorakis. Photo: Supplied

Cleo Nikakis in her youth

The more established immigrants benefited from the new arrivals who laid their money at their Greek venues – and it was lucrative business. “My great uncle George wore four piece suits, had a cigar in his mouth, drove a jaguar and lived in a mansion,” Fiona says.

“My father also made money very easily, through hard work, but he also played hard. His passions were soccer, politics, cards and kafenia, and he was one of the most exceptional self-taught cooks I met in my life. You couldn’t replicate his food. He learnt from somebody who came here from Egypt, who was apparently a good chef. And though he didn’t have much to do with restaurants in Crete, he loved cuisine. In fact, he died at Queen Victoria Market from a heart attack in 1977 while buying fresh food for the restaurant.

“He also loved life, and was very successful because he was one of the early great networkers. People knew him and were drawn because of his persona, but it was when that was put together with my mother’s intellect, amazing cleanliness and business sense that they really became successful.”

Recipe for success

Cleo (Kleanthe Siganakis), came to Australia aged 17 in 1948, a reluctant bride, fresh from high school where she was at the top of her class, leaving behind dreams of tertiary study to meet and marry a man who was 17 years her senior and whom she had never met.

“She came into a wealthy home, my uncle’s home, where she stayed until she got married,” Fiona says. “They were lovely people and she formed a lifelong friendship with my uncle’s daughter Esther. They took her to the best store Georges on Collins Street to buy her Trousseau, the finest at the time.”

The wedding reception as at Michael’s cafe in Lygon Street, and the couple lived upstairs. Cleo set to work learning English, which she was able to speak flawlessly later on in life. “And might I add, with no accent. She spoke perfect English,” Fiona says. “When we were young we would correct her and she would self-correct because my mother loved learning and culture. She never managed to finish her education so placed great emphasis on it, and that is why my brothers and I all went to university.”

None of the children, however, wanted to carry on the family business, despite the fact that in the 1970s Xenia was considered one of the finest Greek restaurants of Melbourne.

“People see cooking shows and think it is glamorous, but it’s not that glamorous and a lot of hard work,” Fiona recalls. “My mother started working in 1960 when I was six or seven, and I didn’t see her much. She worked long hours and proved to be an astute business woman. She loved business and people, and was a feminist before her time. But I was heartbroken that my mother worked so hard. I didn’t feel that what she had was a real quality of life.”

Now, Fiona remembers those years with nostalgia. She understands that her parents weren’t just running restaurants to make money but involved in a reciprocal relationship with the Greek community.

The family with Cleo, who passed away last month, aged 90.

Reciprocal relationships

Fiona, and her husband Peter Strintzos, remember early Greeks like Theo Marmaras who would help out Greeks coming to Australia, who paid their fares in instalments. “I remember Theo saying to me once, ‘I’ve never lost a lira from a Greek,” Peter says. “Back in those days, what Greek people were was different to the Insta society we’ve got now. There was follow through.”

Peter waited tables at the Nikakis family restaurant as a part-time job after he finished his VCE, and he remembers Michael feeding poorer countrymen, supporting those with mental illness at a time when it was not recognised or properly treated, and even offering unnecessary jobs to those too proud to get help for free.

READ MORE: Cleo Nikakis, a life fully lived from Chania to Lonsdale Street

“I think anyone who came from Crete probably passed by one of my father’s restaurants,” Fiona says.

It was a tight-knit community who stood together in the face of racism. Fiona, who says, she never felt racism growing up recalls things not being the same for her father who was called a “dago” and a “wog”.

In fact, just 10 years before Michael’s arrival to Australia on 1 December 1928, Melbourne had been rocked by the sound of two explosions when The Akropolis Club in Lonsdale Street – a premises owned by Samian immigrant Nikolaos Manolitsas since 1923 – found itself at the epicentre of one of Australia’s first acts of terrorism, an alleged racial hate crime, the implications of which would reverberate within legislation, see the matter reach the High Court, and give rise to questions of conspiracy and allegations of police misconduct.

In the face of hardship, the community stood together. They helped each other and felt a deep sense of trust and connection. “My parents were ‘Christians’ and philanthropists in the true sense of the word,” Fiona said. “People would walk off the street penniless and my dad would just take them in and feed them.”

She remembers her parents as true pioneers. “There was none of this, ‘we’re only staying for five years’,” Fiona says. “They were here to stay.”

And it was that attitude that created the strong foundations of Australia’s Greek community.

Michael’s letter to Cleo, not a love story but tender nonetheless

My dearest Cleo,

I have been advised by our parents of the happy occasion of our engagement. it has pleased me very much because I will be united with a daughter of a very good family, and we will secure our future life together.

I received your paper with power of attorney and photograph and I will endeavour to get the permit which I don’t believe will take long.

Coming to Australia, you won’t be with strangers. We have quite a few family members and countrymen. i am sure we will have a good life and get on well.

I apologise for my brief letter but once I receive your reply, I will write more.

Warm regards to our parents and family, and you have regards from my brother and uncle, aunty and all my cousins.

I kiss you, your fiancee,

M.K. Nikakis

I await your reply and look forward to meeting together.