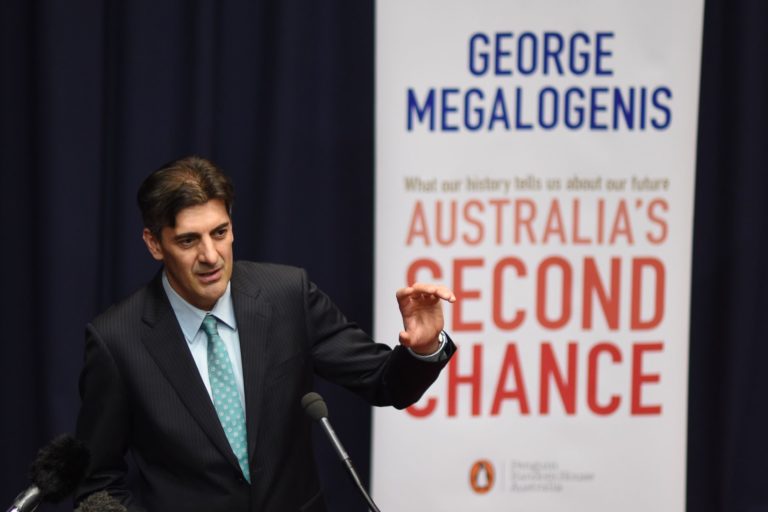

Journalist, author and political commentator George Megalogenis has made a unique contribution to Australian conversations about migration, politics and our shared potential.

He first met Natasha Cica – the guest co-editor of The European Exchange – in 2003. She heard George speaking on ABC radio in Melbourne about his newly published, first book Fault Lines: Race, Work, and the Politics of Changing Australia (Scribe), and interviewed him for a story about Australia’s race politics for the South China Morning Post.

Since then, the two have kept talking on this topic. They caught up for another instalment over lunch at this year’s Adelaide Writers’ Week in March. This edited transcript of their discussion explores Megalogenis’ latest thinking about how contemporary Australia has been shaped by the experiences of European migration.

The latest Griffith Review brings together Australian and European perspectives to explore the ongoing cycle of transformation and exchange.Neos Kosmos, in conjunction with the Griffith Review, are giving away five copies of GriffithReview69: The European Exchange, edited by Ashley Hay and Natasha Cica, and published in partnership with the Australian National University griffithreview.com.To enter, read George Megalogenis’ ‘Underwog’ in Neos Kosmos and answer the following questions:(1) What is the trickiest challenge for migration in the 21st century?

(2) What are the characteristics of an ‘underwog’?

Email your answers to editor@neoskosmos.com.au by 14 October. Winners to be announced in the issue of 17 October.

You can measure the success of Australia’s post-World War II migration program in terms of small business success and home ownership for the first generation, and educational and professional excellence for the second generation. The data has been telling us consistently that Australian-born children of non-English-speaking migrants outperform their peers. And then in the third generation, it returns to the average. I think there’s something peculiar about the drive of immigrant parents, who make sense of the trip to a place like Australia through their kids’ achievements. In Australia, we’re talking about big migrations that began with displaced persons from countries like Poland after World War II, and then the wave from the 1950s and 1960s from Italy, then Greece, the former Yugoslavia.

The children of people from those three southern European source countries – the second generation of those concurrent waves – pop out the same way. So it’s not specific to the Greeks, it’s not specific to the Italians, it’s not specific to the former Yugoslavs. It is specific to the time and place in Australia – and it repeats with the Vietnamese, too, who arrived in the second half of the 1970s and into the 1980s.

It’s not that my parents’ generation walked into a full-employment economy in the 1950s and ’60s and I had free university education in the 1980s that made me privileged. The Vietnamese landed in a broken ‘old’ economy, in a relatively high unemployment period and a political environment that was questioning whether we made the right decision to bring them in; whereas the Greeks, Italians and Yugoslavs had a bipartisan welcome mat rolled out. But overall, the kids of all these groups achieved very similar outcomes. Yet the second-generation kids of the ten-pound Pom wave, which came out at the same time as our parents, didn’t achieve the same outcomes as the second-generation kids of non-English-speaking migrants.

READ MORE: George Megalogenis on Australian values

Why? One of the things that’s well outside my area of speciality, but that people who understand neural pathways should be investigating, is what’s happening for kids who need to think in two languages before they enter primary school. Greek was spoken in our home, and my dad taught me English. So I went to school thinking with two brains. I could speak Greek and I could read and write it, up until the point I stopped going to Greek school. Then I changed schools in Year 3; it was much more Anglo. Maybe you don’t notice the w-word – wog – when you’re five, six or seven, but you do when you’re eight, nine or ten. I very quickly went from happy kid to outsider.

Then in high school, I started to feel like I belonged again. That was a selective government school in South Yarra: Melbourne High. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were a lot of kids there like me.

For my 2015 documentary Making Australia Great, I went back to Melbourne High and interviewed its principal. The way Australia’s migration program works – and the way he explained it – was that ten to fifteen years after the arrival of a group, the Australian-born kids from that group would start to appear at Melbourne High. In the 1950s it was Jewish kids, then southern European kids, then South-East Asian kids. Then kids from continental Asia, and now Africa. So I asked him, because it’s always intrigued me – did you get a second wave? And he said no. There wasn’t a double Jewish, Italian or Greek wave, meaning there wasn’t that third generation. He thought that the particular juice in a newly arrived migrant household, with the kids born in Australia, pushes them to achieve a little further than anyone else.

More anecdotally, it looks like you never get a repeat wave – the kids of the migrant kids. Because that next generation doesn’t qualify for the selective entry. I’ve listened to some of my Melbourne High peers say, ‘But why didn’t my kid pass the exam?’ It’s because the kid who beat your kid in the exam is you thirty years ago. That doesn’t mean your kid is dumb; you should still feel special about yourself, and about your own kids, because they’ll probably do well in the system. So your kid is fine. Your kid is a member of the middle. Your parents started at the bottom, you moved up from there and your kids settled. And if your migration program is working properly, you don’t want your kids to be crowding out the next wave. If they do, that suggests something that’s clearly not true – that one particular migrant group was better than all the others. Much as you would like to think that about your group, it is unlikely that your particular cohort was more intelligent than any other wave that followed.

THE TRICKY THING

The tricky thing for Australia in the twenty-first century is we’ve moved from a migration program that delivered workers for an industrial and service economy – men and women in factories, women in cleaning jobs or working as nurses – to a situation where we’re running a demand- driven migration program that lands the new arrivals at the point I’m at now, as a second-generation migrant. Today’s first generation doesn’t start where my parents started. It starts where my cohort ended up. So the Chinese and Indian wave arrived better skilled – there’s also a smaller wave of skilled South Africans, Kiwis and British immigrants – but my parents had to wait a generation for their kids to be better educated than the population at large. That’s a tricky immigration challenge. This takes us away from the old two-generation integration model. That model gave the opportunity to people from a broken country, people who aspire to leave a place because it can’t contain or satisfy their ambition – Australia is not actively recruiting those people now. We’re now on the receiving end of a very big self-selecting wave.

READ MORE: George Megalogenis on Australia’s Second Chance

That poses two big risks. One is that Australia is a posting, not a home. These migrants have chosen to come here, but their loyalty can then be counterbid by another country that gives them a better settlement deal – because every country, for ageing population reasons, will be bidding for the same people. The other risk is that their cultural identity is already formed, and it’s a middle-class identity with links back to mother countries, through technology and the opportunity to travel back there at least once or twice a year. My mum didn’t make her first trip back to Greece until 1976, after fourteen years in Australia. It’s quite exciting for a country to be so connected to the world. But it’s very difficult for a nation state, a country with as complicated an identity as Australia’s, to be able to guarantee the integration and loyalty of migrant waves that self-select it. I’m not looking at the past as the ideal integration model – our European parents were pretty much bullied into becoming Australians. And they got their own back – not at the expense of the country, but by creating the second generation that was as Australian as any generation will ever be. Our generation, that second generation, doesn’t think the way old Australia did – we are new Australians. But we’re in the middle. So, the first-generation migrant of the twenty-first century lands in the middle – but doesn’t necessarily feel like part of the middle in the same way we do.

POST-WAR MIGRANTS

If your family were post-World War II British immigrants, or even Jewish immigrants from Europe with a connection to Israel, or contemporary immigrants from the Indian or Chinese middle class, there are strong opportunities to maintain those connections to the mother country, including professional connections. Again, that’s not at Australia’s expense and can be quite healthy. So ‘Chinese Australian’ today can mean China and Australia, ‘Indian Australian’ can mean India and Australia, and ‘Jewish Australian’ can mean Israel and Australia. But a number of broken countries have contributed large numbers of people to Australia from places destroyed by wars, places that literally can’t maintain that kind of connection or support; that kind of dual identity. So the relationship is different. For example, Israel’s contemporary relationship with Australia is different to the relationship that Poland might have had with Australia after World War II. I grew up in Caulfield, so I’ve lived with people who survived the Holocaust, barely – and I’ve lived with people who were virulently anti-communist, because they survived that. If we talk specifically about Greece, Australia entered a joint migration deal. From the 1950s, Australia brought out a lot of men to work in industries, and then in the 1960s a lot of women. We’ve done this in various iterations before – think about the wool boom of the 1830s and ’40s. There was a lot of assisted passage to bring shepherds out, and then Caroline Chisholm hopped in and said ‘We’ve got 60–70 per cent men, we need to bring some girls as well.’ It’s sort of a standing joke that we re-created that history in the 1950s and 1960s without realising it. Some well-meaning people who think they understand Greek culture will say to people like me, ‘Your mum and dad met in Australia, right?’ Sure. ‘Was it an arranged marriage?’ Absolutely – Robert Menzies arranged it. He let Dad come out in the 1950s and he wanted Mum to come out in the 1960s. He had no idea they’d meet in Carlton and get married. They came from different parts of Greece, and each of those two families had no idea that the other existed in Greece.

Greece is one of those unusual places that picked another fight after the end of a world war. There was a conflict with the remnants of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, and a civil war after the end of World War II, which was already pretty much underway before the main conflict in Europe ended in May 1945. That country clearly has a governance issue. It then went into a blinking on-and-off democracy/junta through the 1950s and 1960s, and it was a very difficult place for people from my parents’ generation to stay connected to in a way that today’s immigrants can stay connected to China, India, Israel or previous British waves did to Britain. So when we look at Australia as a British colony, really a province of Britain, and our relationship with the mother country, we have all these cultural quirks. We feel like we are more egalitarian than the British – now I’m adopting a collective Anglo ‘we’, or a collective Anglo-Celtic ‘we’ – but we still feel that it’s home. We go back to it. We kind of recognise it and we kind of don’t recognise it. They know who we are, we know who they are.

MEMORIES OF YOUTH

Going back to my twenties – why didn’t I go global? Good question. I think I was learning too much about the way power operated in Australia. I had a good job in journalism, and my mind was open enough to get something out of it. If had been thinking globally, I would have gone to Britain or the United States. I certainly wasn’t thinking Athens. I don’t know what would have drawn me back. Would I have traded a job in the Canberra press gallery at probably the most interesting time in national affairs in fifty years? For – what?

Would I go global now? Yes, I wish I could, and that I could have done it in the past decade. But I have limited tools – I work in print, and a bit in television. And I’m a translator and an explainer. In terms of the things I understand about Australia, if I could apply a version of that understanding to the US or Europe, I’d love to go there. But no, I still don’t have any particular pull to Athens. The difficulty for me now is the language. I’ve lost it. I couldn’t walk into Greece on my own terms. I’d be compromised. This wouldn’t have been an issue if, say, Greece had found a way to lure me in my early twenties, maybe to be a freelance journalist covering Europe. My personal example is neither here nor there. But thinking through the structural lessons you can draw from this kind of example, Australia has been able to convert me into a professional better than Greece could have enticed me back for reasons like family connection. And people often forget that Greece theoretically had a larger population than Australia at the end of World War II. So Greece’s relationship with Australia is very specific. Australia grew at Greece’s expense.

Let’s go back and look at the 2007–08 global financial crisis. Let’s imagine the soft landing had been in Europe, and the hard landing in Australia. And that Greece wasn’t made an example, but Australia was made an example. That we repeated our history of the 1930s Depression, when the Bank of England sent their team down to tell us how to cut public service wages and how to cut public spending, gifted us an unemployment rate pushing 30 per cent, in our national interest, and said we should pay back all our debts. If those roles were reversed, yes, I would have left Australia. Probably for the US. Even though it went through its own GFC episode, I think by then I would have known enough about the world to make a second life there. So even if Greece represented an emotional pull, or even if it had been more economically stable relative to Australia, it’s not the next place I would have thought to go.

But yes, I’m a Greek. I think Greek. Many years ago when Greece played Australia in that friendly before Australia went on to the soccer World Cup in 2006, you asked me who I would support. Greece had just won the European Championship. That was a bit like Richmond winning the Australian Rules Football premiership a couple of years ago; it was the thing that was supposed to never happen. And that was a glorious thing. So Australia was up against Greece, without much chance of winning.

Do you remember my answer? I said, ‘Don’t attribute it to me now – but I’m going for the underwog.’

George Megalogenis is an author, commentator and journalist with three decades of experience in the media. His most recent books are Australia’s Second Chance (Hamish Hamilton, 2015) and The Football Solution (Viking, 2018). His essay ‘Time to trade in’ was published in Griffith Review 41: Now We Are Ten.

His essay ‘Underwog Migrant integration and influence in postwar Australia’, is republished with permission from GriffithReview69: The European Exchange, edited by Ashley Hay and Natasha Cica, and published in partnership with the Australian National University griffithreview.com