Nana Mouskouri and her music transcends generations and in the case of Ashley Dyer, holds a very special place in her family.

Ms Dyer is a Melbourne based self taught fashion designer and maker, who places great emphasis on making sure her brand is sustainable.

In preparation for a cousin’s ‘pop star’ themed birthday, the Uncle Phuncle founder paid homage to her family’s beloved pop singer, whipping out a blue maxi dress she had sewn together a few years prior, popped on a wig and Nana’s signature glasses.

“Going to party full of Greeks I thought I had to play to my audience here and go as Nana! Nana has always been so treasured in our household. In 1985 my dad actually directed The Mike Walsh Show and got to meet her and yiayia and pappou were in the audience that night,” she told Neos Kosmos.

Before making her way over to the celebrations, Ms Dyer had to show one very special person in her life the final product.

“I didn’t tell yiayia, I just told her we’re going to come to your house to visit you before the party. She’s always waiting outside ready to greet us and as I walked up the steps she said ‘Mouskouri!’ so she knew straight away,” Ms Dyer explained laughing.

“She loved it so much and so she went and got her records out and we took a few photos. She couldn’t believe it, she was so happy and said ‘you’ll be the only one as a Greek singer there’, and she was right because everyone had gone as the typical rock stars. But thankfully everyone knew who I was straight away.”

READ MORE: Q&A goes gaga over Nana Mouskouri

Many grandchildren of migrant grandparents know all to well the sacrifices their elders have made to be where they are today and Ms Dyer’s yiayia Frosso Kontis is no exception.

“We are so close. Yiayia is honestly one of the strongest women I know of, she has been through so much in her lifetime, I think a lot of immigrant have a lot of very powerful stories. She got through World War II and surviving that, she came from a small village in Greece, her mother passed away at a young age, her father was the village priest and teacher and so she had to care for her whole family. She had to leave school when she was 11,” Ms Dyer said.

“She’s such an incredible woman, she also overcame breast cancer in the 60s which was a huge feat back then.”

It was only earlier this week when Ms Kontis celebrated her 97th birthday and the young fashion designer says that no matter her age, yiayia Frosso has never been out of style.

“Honestly she’s the only grandmother I know of who can buy a piece of clothing for a teenager and it be in style. She has impeccable taster and always has. She’s always loved fashion and had an eye for style. She doesn’t go on trend, she just has timeless fashion sense,” Ms Dyer said.

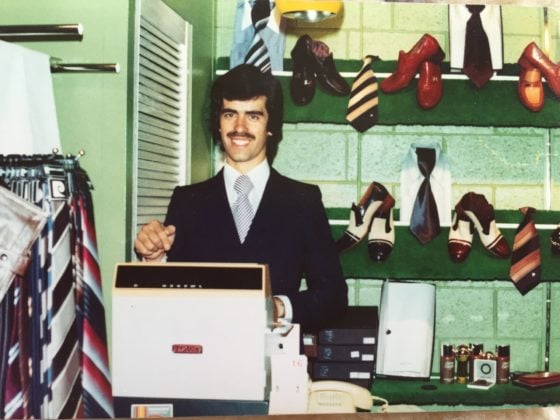

It is in this way that one can tell how important and prevalent fashion has been in Ms Dyers life. Her uncle Nick Kontis even had his own store called “Clothes Circuit” making bespoke pieces back when the Highpoint Shopping Centre was first opened.

It was however her own disappointment in the lack of clothing she saw herself wearing that really put her on the trajectory of starting her own clothing brand.

“I started sewing out of pure frustration of not being able to find what I wanted to wear in stores but now it’s taken on a whole new meaning. I think it’s just so important for me to keep production local, I mean I make everything myself. But slow fashion is just so important now, it’s not enough for us to think ‘oh wouldn’t it be nice if the fast fashion industry could change and workers got a fair wage and didn’t bring the planet to it’s knees’. But it’s not enough now, it has to change,” she said.

Ms Dyers label is a melding of classic 60s and 70s design with a 21st century twist, but above all and most importantly to her, is that all of her work is produced locally. Often at times this means that prices may be judged as expensive, but consumers often do not know what happens behind the scenes when they purchase a cheap t-shirt.

“Undervaluing the craft and workmanship of clothing in general has happened because of decades of underpaying vulnerable garment workers overseas, which the majority are women in vulnerable working and living conditions,” she said.

The term ‘slow fashion’ has steadily gained popularity in the mainstream fashion world, with environmental advocates pushing for the mass production of textiles and clothing to essentially ‘slow down’.

Secondhand or thrift shopping is often encouraged in the push for more sustainable consumer practices, but often sizing is often not as inclusive as it should be to make this a sustainable practice. Additionally, cost is often at the forefront of these conversations when it comes to making slow and ethical fashion accessible to all consumers.

READ MORE: Sarah Kokkinos turns secondhand shopping into an experience of its own

Ethical fashion does come at a cost and for those with their own labels the overall cost of the product comes down to making sure everyone in the process of creating the final product gets paid fairly.

Ms Dyer makes all of her clothing on her own in her Brunswick studio, sourcing and printing her textiles locally thus leaving her own mark on the billion dollar industry. Uncle Phuncle however, is still a speck like many other local fashion labels, in the fashion market sea.

“Obviously me being such a small label, there’s only so much I can do, it is a huge issue and I don’t claim to be an expert but I do believe we as consumers do hold the power. The small purchasing decisions we make can have a large impact overall…It can be as simple as just cutting down the amount of clothing that you buy, it’s not an all or nothing thing,” she explained.

The world of fast fashion is a fairly new concept in the grand scheme of the modern industrialised world, with one turning point being the popularity of the shopping centre.

Australia’s first shopping centre opened in 1957 in Brisbane with 25 retailers and now the number of centres has climbed to a whopping 1,603.

“The fast fashion machine is relatively new in human history, just in the 60s and 70s people were still making their own clothes and also valuing their purchases. To buy a winter coat was a big deal. It really wasn’t until the 80s with the explosion of the modern shopping centre and mall where things started to really change and I think in the 90s it really got its stride going. Now we have a whole generation of people who don’t know what it was like to make their own clothing,” Ms Dyer said.

Ms Dyer’s uncle Nick even fell victim to the mass production monster and had to shut shop.

“My dad’s brother, he had a fashion store when Highpoint first opened in the late 70s and he and his business partner designed and had their clothing made locally in Brunswick. This was at the cusp of everything being outsourced and mass produced overseas…The reason his business didn’t survive was because he couldn’t compete with the new miniscule prices that other people were charging by having things manufactured overseas,” she explained.

Despite all of this and the new era of online shopping which has in its own way fed the monster, Ms Dyer remains hopeful that in coming years, change will happen at more significant rates.

“What I’d like to see is a return to local industry, that would be fantastic and if there are more local labels manufacturing locally the industry will start to grow again. If it’s locally made you can learn more about the history of the garment and you feel closer to it and treasure it more in your wardrobe,” she said.

“We are so far removed from the five dollar t-shirt that we buy at a fast fashion store. Part of my job is creating a story around my label and communicating to people that I made this myself and that you will treasure it because I treasured making it.”

READ MORE: Rising to the occasion: Greek-Australian fashion designer Kianna Magelaki on beating self doubt

If anything Ms Dyer sees local production as more of a sense of togetherness and community rather than a rivalry.

“As designers we can’t aspire to the fast fashion business model anymore because it’s destroying our planet…If I see other small fashion labels in Australia popping up I don’t see them as competition, I think it’s fantastic, because the best thing we could provide consumers with in a world where we want to promote slow fashion is choice,” she said.

Whilst manufacturers have a massive role in preventing the collapse of the environment, consumer practices can greatly impact how the industry changes.

“It’s not an all or nothing thing, you shouldn’t feel shamed for buying fast fashion. If you can buy one piece that’s ethically made, that’s fantastic. You don’t have to throw out your wardrobe, in fact that the opposite of what we want.”

Ms Dyer’s message is clear and simple, “small baby steps make a big impact overall”.