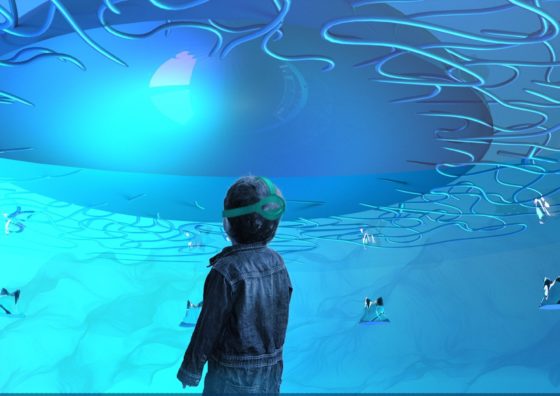

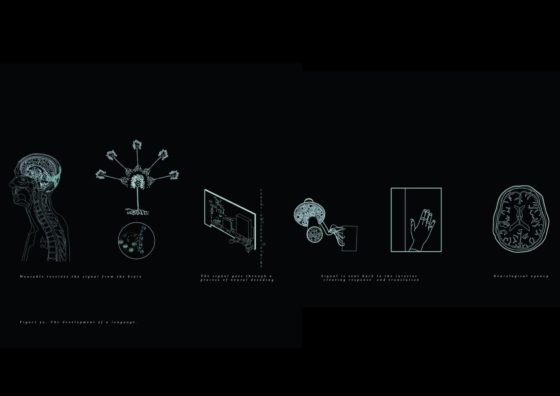

“What if space had the ability to act as an interpreter, reading the minds of its users to communicate as well as exude a sense of agency and perspective?” Greek Australian interior architect Ilianna Ginnis wondered, as she started designing her honours project, “Neural Sensorium”, in Monash University a few years ago.

“I wanted to imagine a space that would be ideal for individuals with disabilities who are non-verbal”, the designer told Neos Kosmos.

It would be a space where technology gives these individuals the power to project images, sounds – all these sensory qualities – through their brain, allowing them to create the space themselves and communicate.

One day this will all be possible, Ms Ginnis believes.

“In the future when there is more research in this field, and neurological technology becomes more accessible,” she said.

“That was the starting point for me. I thought ‘big’. But now, with my PhD, I am honing in on the specifics. I am thinking at what is possible now. I am observing and working alongside people with disabilities, as I design their space.”

Ms Ginnis’ passion to help people who are nonverbal started from a very young age.

“My younger sister was born with a disability and I grew up with her journey, seeing her needs. I became empathetic towards other people and thus grew my strengths in wanting to help this community and especially helping people who can’t speak, because I knew the difficulties my sister faced.”

READ MORE: 10 (+1) Places to visit in Athens if you like design and architecture

Designing with empathy after years of experience as a caregiver

Currently a PhD candidate, Ms Ginnis creates systems of communication for people who do not use verbal language, and she also works as a designer with Visionary Design Development, a firm that designs solutions, built-in environments for people with disabilities.

However, from the moment she started her studies at the age of 18, she also started working as a caregiver across many fields of disability. Up to this day, she cares for adults and young kids, even elderly people with dementia and essentially those with a cognitive disability that have struggle to communicate verbally.

“As I come in with the design, I am their voice. I interview their family, and then I test the space with them, the textures. I sit there observing their needs and provide them the platform to tell me what they want, and how they need their space to respond to them. I look at the needs of the individual first, and then how the space functions for them,” Ms Ginnis said, referring to her role in the design of Kilmiston Respite Home, a place that was created based on the needs of the non-verbal people.

Ms Ginnis also works in the space as a caregiver, so she has firsthand experience of the benefits such an environment can bring when designed to cater to the needs of those occupying it.

READ MORE: Alex’s lights bring the joy of Christmas to Autism Australia

“Their sensory issues communicate with the space. They all share their needs without confronting or seeing their needs clashing. They spent multiple times in the different spaces, depending on what time of the day it is and what their needs are. They are much happier, they do not rely on medicinal uses so much, because the space is light and vibrant, with natural materials, with ‘shadow and reflection’ spaces that give them a sense of calm.”

Public environments ignore needs of non-verbal people

“Through my PhD, I noticed that public environments do not consider people who are nonverbal. There is a massive missing gap, in museums, in civic spaces, galleries, shopping centres. There is a lack of consideration. Shopping centres especially are very loud, very bright, very crowded and overstimulating. There are no spaces where the individual can collect their thoughts, and people with a cognitive disability will get overwhelmed and overstimulated. People who think differently and who don’t act in a social construct aren’t considered in these environments,” she said.

The full experience of life for every being, seems to be central in the projects Ms Ginnis takes on.

“For me the most important thing is people. I really care about people and how people feel. And because we are changing and the world is evolving and there is more freedom of expression, I tend to follow and get involved in political, technological, gender debates, that will actually help the individual be more accepted, and have more agency within the environment.”

Though her passion is clearly for assisting the nonverbal communicators, her sense of curiosity and her empathy takes her down different fields where there is need.

“I like to delve into issues, to go deeper than the surface. Design gives me the opportunity to explore all these issues creatively. What is a contemporary issue and how can we help people in diversity explore themselves in the environment. Everyone should have a space where they feel most comfortable and architecture provides all that.”

Empathy and curiosity drive her. “Empathetic architecture is my starting point. Before I start I want to know about the individual – to put myself in their shoes. What is their lifestyle like, what are their needs, their challenges, what are their goals.”

Her dream is to break down these barriers so that people who are nonverbal can actually communicate their needs. Their language is internal and communicated through their behaviour, so another aspect would be to develop that language which would lead her down her ultimate goal, which is to ensure that people with a neurological disability are no longer marginalised, and their needs are met, in both public and private spheres.

“So someone like my sister can experience space and have power in her space, so she doesn’t need to rely on other people constantly. So she can actually be free to make her own choices”.

The ideal way to get there, according to Ms Ginnis, would be if the designer worked with all the practitioners, such as occupational therapists, speech pathologists, developmental psychologists, when they design their spaces. “If we all worked together, the result would be better. Because the clinical side provides an understanding of the individual’s needs, whilst the design is very much about how we fulfil these needs.” This ‘synpowerment’ is what she is currently researching in her PhD.

READ MORE: Impressive State Library revamp bears a Greek stamp!

Often, Ms Ginnis names her projects in Greek – “Stigmi” (meaning Moment) or “Pnevmatikos” (meaning Spiritual) for instance – as she feels strongly connected to her Greek roots.

“I tend to name my projects Greek names as it is my identity. It has played a big role in my life . Our culture is very empathetic, we connect through people and we are very human-centred, which is something I adapt into my work.”

For more information about Ilianna Ginnis and her inspiring work, visit www.ginnisdesign.com