The media played a pivotal role in the history of Modern Greece going right back to its beginnings. The Greeks, through their network of friends around Europe, ensured the struggle for independence from Ottoman rule was not far from the front pages of European newspapers even as their governments tried to ignore what was going on in the eastern Mediterranean.

The media of the day kept the pressure on their governments to act until they grudgingly did so to telling effect. In this year of the 200th Anniversary of Greek Independence, it is a good time to look at the contribution of journalism to the story of Modern Greece.

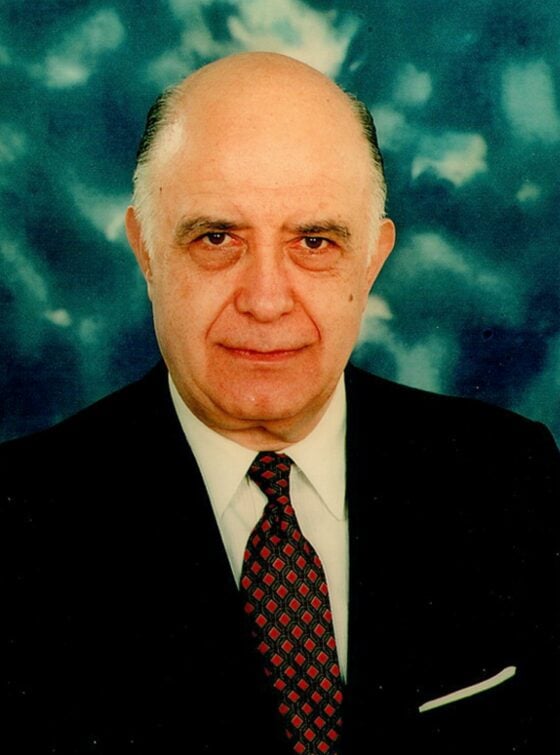

One such story would have to be that of award-winning Greek newspaper journalist Elias Demetracopoulos, the 2008 recipient of the Order of Phoenix for “outstanding services rendered to Greece in his capacity as a journalist “… and his “history of opposing Greece’s military dictatorship”. His is a story of many dimensions covering a watershed time in Greek history that is fit for a movie or a television series.

An established journalist for leading Greek newspapers, Mr Demetracopoulos fled the country in fear of his life when the military overthrew the government in 1967. He found refuge in Washington where he lobbied tirelessly for the return of democracy despite open hostility from the US establishment and from leading Greek-Americans who threw their weight behind the junta.

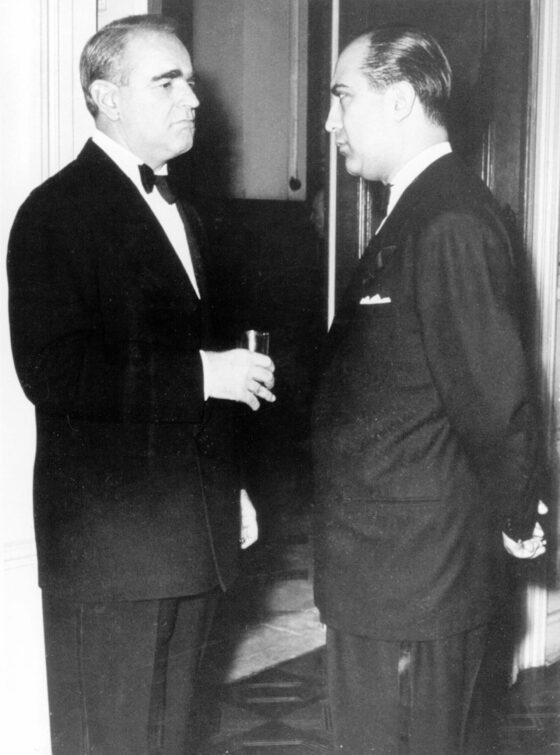

Even as he worried about his immigration status in the US, Mr Demetracopoulos uncovered evidence that Greek-American magnate Tom Pappas had secretly funnelled a “donation” of $549,000 ($4 million in today’s money) from the Greek military junta into Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign. In the years before the 1967 coup, Mr Demetracopoulos had exposed the magnate’s dealings with the Greek government and there was little love lost between the two men.

READ MORE: Junta’s 21 April anniversary, a dark day in history for those in Greece and Greeks abroad

Had the US media made proper use of the Demetracopoulos story, it is doubtful Mr Nixon would have won the 1968 election. A lesser scandal had cost Mr Nixon the presidency when he narrowly lost to John F Kennedy. As it was, Mr Nixon won the 1968 election by less than one percent of the popular vote.

Mr Pappas was to be identified as the “Greek bearing gifts” in the Watergate tapes that eventually led to President Nixon resigning in disgrace in 1974. Mr Pappas was implicated in bankrolling the team of burglars who broke into the Democratic Party offices in the Watergate Hotel sparking the scandal leading to Nixon’s eventual disgrace.

What is truly remarkable in all this was how Mr Demetracopoulos, a political refugee, living on limited resources, without backing from any media outlet and the open hostility of the US administration was able to get so close to the levers of American power that he threatened the outcome of a presidential election. He was the lone voice in the US that kept constant pressure on the junta.

American investigative journalist and academic James H Barron set out to write a book on the Pappas link to President Nixon and the Watergate scandal.

He changed tack the more he learnt about Mr Demetracopoulos. Mr Barron went on to spend five years carrying out research to write a book on the enigmatic Greek journalist. The result is his acclaimed 2020 book, ”The Greek Connection: The Life of Elias Demetracopoulos and the Untold Story of Watergate”.

“He (Mr Demetracopoulos) was a difficult subject to write about. He did not want to talk about his private life or his emotions and steadfastly resisted divulging the names of sources, long after the sources had died,” Mr Barron told Neos Kosmos.

“At least three others had started to write his biography and gave up. It took me months of face-to-face interviews and years of effort to get to know him,” Mr Barron said.

“I have boxes of his personal files and I must decide where to donate them. This material includes his Order of Phoenix citation and medallion, his State Department, CIA and FBI intelligence reports (on Mr Demetracopoulos himself), and private correspondence.”

Mr Demetracopoulos was marked by a special kind of courage from an early age. He was just 12 when the Germans entered Athens and despite the dangers, he helped stranded Australian soldiers make their escape to Crete.

He then joined Organosis Anasteos Genous (OAG), a small Athens-based resistance group. One of the group’s early successes was an attack on the airfield Tatoi in which 15 warplanes were destroyed.

As a member of the OAG, the young Demetracopoulos learnt to seek out important information without drawing attention to himself. He learnt to retain what was relevant and to compartmentalise the information and keep it to himself until needed – skills honed by war that he employed as a journalist.

He also carried explosives and acted as a lookout in sabotage operations.

The Germans arrested Mr Demetracopoulos on 13 September, 1943, when dressed as a German soldier he tried to take weapons from Italian soldiers left stranded by their country’s surrender to the Allies. He was brutally interrogated but did not divulge any information and was sent to Averof Prison.

Mr Demetracopoulos was again punished when he tried to smuggle out a letter for Australian prisoner of war Captain Jack Lewis to send to his family in Sydney.

The young Demetracopoulos was eventually transferred to the Egnition Home for the Insane and saw out the rest of the war pretending to be insane to stay out of prison. Mr Demetracopoulos determined that he would never give in to anyone whatever the threat.

One of his first acts after recovering at home was to commit to paper what he remembered of the letter that Captain Lewis had given him. He sent what he remembered to Captain Lewis to his brother in Sydney. Mr Demetracopoulos was never to discover whether Captain Lewis survived the war or that his letter was received in Australia.

READ MORE: The dictatorship: the Greek-Australian response to the junta

Soon after liberation, Greece was engulfed in civil war. In 1946, the US replaced Britain as the main power broker in the region. US president Harry S Truman announced that “Greece must have assistance if it is to become a self-supporting and self-respecting democracy. … There’s no other country to which democratic Greece can turn.”

The American presence and influence grew as a result and this marked a significant shift in Greek politics and Mr Demetracopoulos was quick to realise this.

He joined the respected Greek daily newspaper, Kathimerini, aged 21 and soon showed his skills as a journalist. During the 1950s and 1960s, Mr Demetracopoulos rose to become the youngest political editor in the country. He had the ability to overcome official obstacles to get the story that no one else could. So accurate were his reports that he was accused of being in the pay of foreign powers or was a stooge of the right and the left.

US State Department and CIA dossiers were compiled on him and these repeated unsubstantiated allegations which served to feed official suspicion of him when he was to later live in exile in the US.

For all the obstacles that he faced, Mr Barron noted: “He (Mr Demetracopoulos) met nearly every US president from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan, and the three he didn’t meet personally (John F Kennedy, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter) definitely knew about him and his activities.”

In 1984, FBI director William H Webster acknowledged that between 1964 and 1974, his organisation had carried out six investigations about him and all had shown that Mr Demetracopoulos was not a threat to US national security. The CIA grudgingly admitted that there was no substance to many of the allegations they made against the Greek journalist over the years.

Before the 1967 coup, Mr Demetracopoulos covered the US for dailies Kathimerini and Makedonia and cultivated important friendships that were to help him when he later fled to Washington.

Over the turbulent 1950s and 1960s, he came to realise that in the growing instability of Greek politics the real threat to democracy was not from conservative right-wing elites but from a group of middle-level military officers linked to IDEA, a secretive ultra-right-wing organisation. As early as 1964, he expressed concern over IDEA’s growing influence and in particularly of one Colonel George Papadopoulos, who was to head the military junta which came to power in the coup of 1967.

READ MORE: No, the junta did not perform an economic miracle

“During the junta years (1967-74), when he was more an activist than journalist, he (Demetracopoulos) usually didn’t write articles under his own name, (an op ed in the “Wall Street Journal” was an exception), but he managed to get articles into diverse publications from the ‘New York Times’ and ‘Times of London’ to the ‘Athens News’,” Mr Barron said.

“He also gave speeches, published a monograph, and ghost-wrote articles and speeches for members of Congress. His activities were regularly covered by columnists like Jack Anderson, Roland Evans and Robert Novak.”

“The Greek-American community in the US was divided, with many more supportive of the dictatorship (and of people like Tom Pappas) … . Greeks in Europe, Canada and Australia were far more unified and vocal in their support for the urgent restoration of Greek democracy,” Mr Barron said.

Over those difficult years, people in Greece relied on Mr Demetracopoulos to give voice in the US to what was really going on in Greece- to the point where postal authorities knew that letters and packages simply addressed to “Elias” or “Elias Demetracopoulos, Washington DC, USA” were to be delivered to him.

“He lived frugally in a shabby residential apartment at the popular Fairfax hotel, filled with his files and other research material. – putting his money into long-distance telephone bills, photocopies of articles, and business luncheons designed to aid the anti-dictatorship cause,” Mr Barron said.

The late Christopher Hitchens, who wrote a paper about the Greek junta’s donation to Nixon based on Mr Demetracopoulos’ findings, said of him: “Elias Demetracopoulos is an illustration of how much can be achieved by a determined and courageous individual.”

Mr Demetracopoulos died from complications from Parkinson’s Disease in 2016. He was 87.

“The Greek Connection: The Life of Elias Demetracopoulos and the Untold Story of Watergate” by James T Barron is published Melville House and distributed by Penguin Random House.