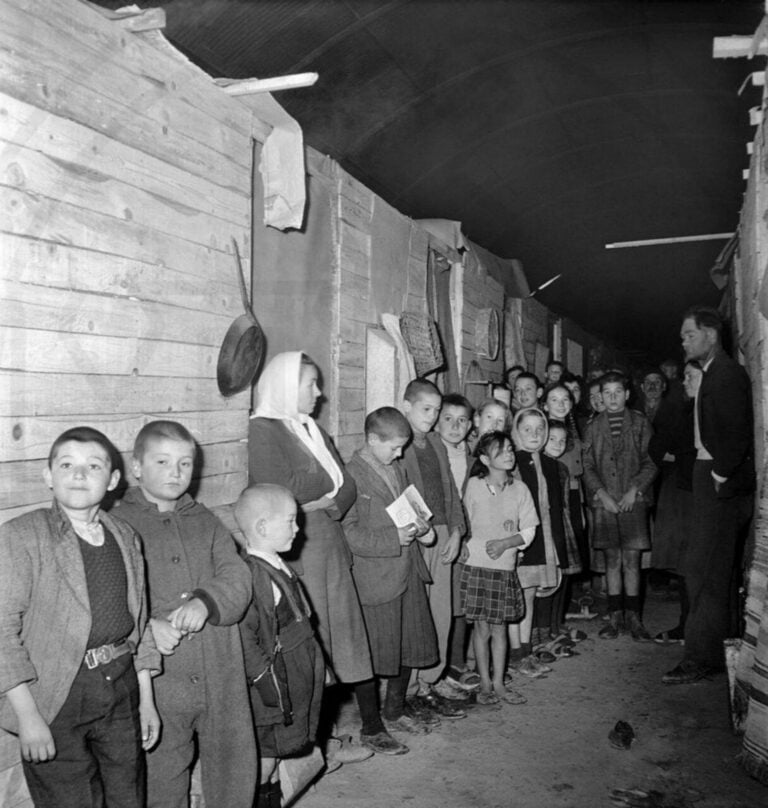

During the Greek Civil War more than 50,000 people died and more than 500,000 Greeks were displaced from their homes. 24,000 children left the country for unknown destinations. By the end of November 1950, 172 unaccompanied children had arrived in Australia.

“How do you find someone in a country that was ravaged by war last century?”

The answer lies in Marjorie Morrissey’s book, “Finding Teo”. The story is a constant back and forth travel in time and place between contemporary Australia and Greece of the post-Civil War period and follows the efforts of a modern Australian family to find a boy lost during those years.

The search took a long time because no one was talking about “Teo” anymore, as his fate became a ‘guilty’ secret.

As the author, Marjorie Morrisey, explains to Neos Kosmos, the book is a fictional work created towards her 2020 Master of Applied Arts and Humanities at the University of Canberra.

Having started her career as an English and Drama teacher, her dream has always been to manage to write her own book. “I spent a fair bit of my life instilling a love of literature, in others, but I’d always hoped that I’d get the time to write and I was lucky enough to be in Canberra, where there was a master of arts in research programme. That was a great place for me to write this book, because I was able to take it slowly, get used to the research world and be guided by university teachers who were also writers”, the author says.

WE CAN BE MORE INCLUSIVE

At the time she started working on her thesis, the refugee issue had again become a global issue with the mass exodus from Syria in 2015, forcing many of the world’s nations to a crossroad as to how to deal with the crisis. Her own family history of migration from Ireland also gave her pause as to the relationship between civil wars and migration. This inspired the central idea of her book.

“I was writing this book and reflecting that, at that time [after the Greek Civil War], Australia and other countries had such a generous approach to refugees. So that rang some resonance with me. And the other, I suppose, piece of the puzzle, was that my own family on the Irish side had had come to Australia via trauma in the 19th century and this might not be the same, but my imagination did go there, to the link that civil war has been such a source of migration forever, but also such a source of trauma forever”.

As Ms Morrissey explains, without wanting to appear preachy, she aims to send a wider message regarding the refugee issues today.

“One aspect of Greek culture that I have always loved is this tendency to integrate others. And the book is a reminder that there have been times in history when Australia has been very good at that. I think in terms of refugees nationally it’s about remembering that Australia was an inclusive country and I hope we can become more inclusive as we go.”

A BOOK FULL OF GREECE

What impressed me while reading the book “Seeking Theo” was how aptly it captures not only the Greek culture but also the very mentality of the Greek family, with repeated references to traditional foods and deserts, specific words and phrases that were used in a very appropriate manner, typical habits of Greeks at the table, the feast and their interaction with others in general.

“I was lucky enough to be able to travel to Greece and visit many places there. I was at festivals and fairs, socialising with people, connecting with them and even a large part of the book was written in Greece. I spent the whole day absorbing as much as I could of the Greek life and at night I would put on paper all the experience and the feeling I had gained,” says Ms Morrissey.

The whole book is imbued with the warmth and realism of the characters who win you over immediately to the extent that they feel like family.

“During the writing of the book, I consulted some Greek friends who gave me some very good advice. What I was very interested in was to show great respect and real love for the characters. So, I treated them as if they were dear family members and I think I finally succeeded.”

A MULTI-GENERATIONAL AFFAIR

What made it difficult for Ms. Morrissey when writing the book was, as she says, its topic. “It was very difficult to write about such a sad topic. “The loss that every family experience is a very sensitive subject,” she says.

Yet she manages to focus on something bigger than the loss itself and that is the relationships between three generations of women of the same family, as they evolve and are strengthened through the common goal of Teo’s quest.

“And that was one of the reasons I was really keen to set it in the now and to have that three generational construct whereby I’m sure it happens in Greek families, I know it happens in my multi multi-generational racial construct, different generations get different bits of the puzzle from other different generations. And even the grandmother – grandchild relationship can be so different from the grandchild – mother relationship”.

Having recently retired from her day job as an executive, Marjorie Morrissey hopes to be able to keep writing stories in the future. As she confesses, that was her plan since she heard a story from “the master-of-the-tale, Brian Hungerford, about why he gave up the day job and pursued his love of storytelling”.