“…There gradually emerged a people, not very numerous, not very powerful, not very well organised, who had a totally new conception of what human life was for, and showed for the first time what the human mind was for”. H.D.F Kitto writes to preface a thesis on Greece’s influence on humanity.

Philosophy was the cornerstone of this influence. A network of critical thought that underpinned and questioned society, improving life through understanding and cataloguing the diversity of the human experience. Socrates was the first to “call philosophy down from the heavens…and compel it to ask questions of life and morality” Cicero writes. The pioneer of modern thought set the tone for succeeding Hellenistic thinkers, and understood philosophy to be practical; useful inasmuch as it could be applied to life. Abstractions on how to live were therefore only useful if they could be interpreted, understood and applied by the masses.

As a student of these ideas, I find it curious how detached my cohort is from the practice of philosophy. It’s pored over and likely understood but seldom practised. Χαράλαμπος (Harry) Κατριβέσης, my 98-year-old grandfather, represents the antithesis of this idea. His grasp of philosophy is culturally inferred and reflected in practice without any erudition.

This inquiry explores the implicit relationship between Hellenistic philosophy and Greek culture through the sustenance of ancient ideas in modern practice. The dataset of Harry’s life synthesises key Hellenistic tenets and display’s a shift from Aristotelean Eudaemonia to Epicurean Ataraxia. A century-long cultural conditioning has made him the perfect conduit to the understanding of ancient ideas, and observing his practice is akin to reading a textbook.

Hellenes were mostly teleological; carrying the belief that everything had an end, Telos, or purpose. Aristotle understood happiness to be the purpose of life, and Seneca writes “life is long…if you know how to use it”. Therefore, understanding how to use life was the fundamental starting point in living well. Aristotle defined happiness, or Eudaemonia, as living and faring well in accordance with reason and virtue.

For Epicurus, the Telos of life was pleasure; our most basic and natural desire. However, he defined pleasure, not as indulgence in gratification, but as ataraxia; freedom from disturbance, feeling neither bodily pain nor mental turmoil. Harry’s formative worldview emphasises Eudaemonia and appends Ataraxia in later life. Without any empirical understanding of either of these ideas, his conduct implies the culturally pervasive nature of philosophy.

Harry and his flock of sheep in the mountains behind Elekistra in the late 1940s. He would take his sheep there every summer and would live in a makeshift hut (Kaliva). Photo: Supplied

Harry, pictured on the right, and fellow villagers in Elekistra the late 1940s. Photo: Supplied

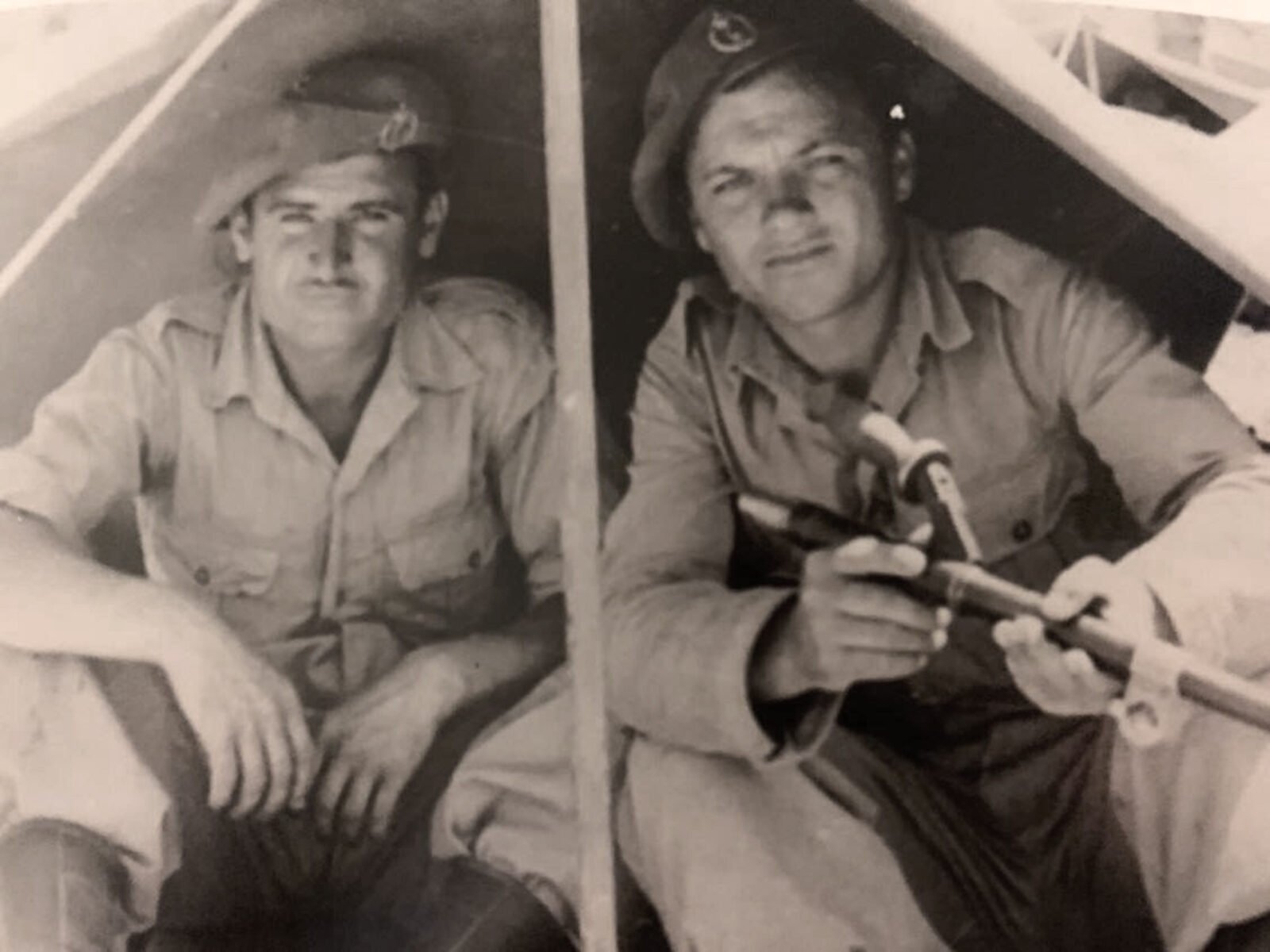

Harry and a friend from the Army during compulsory military service in the early 1950s. Photo: Supplied

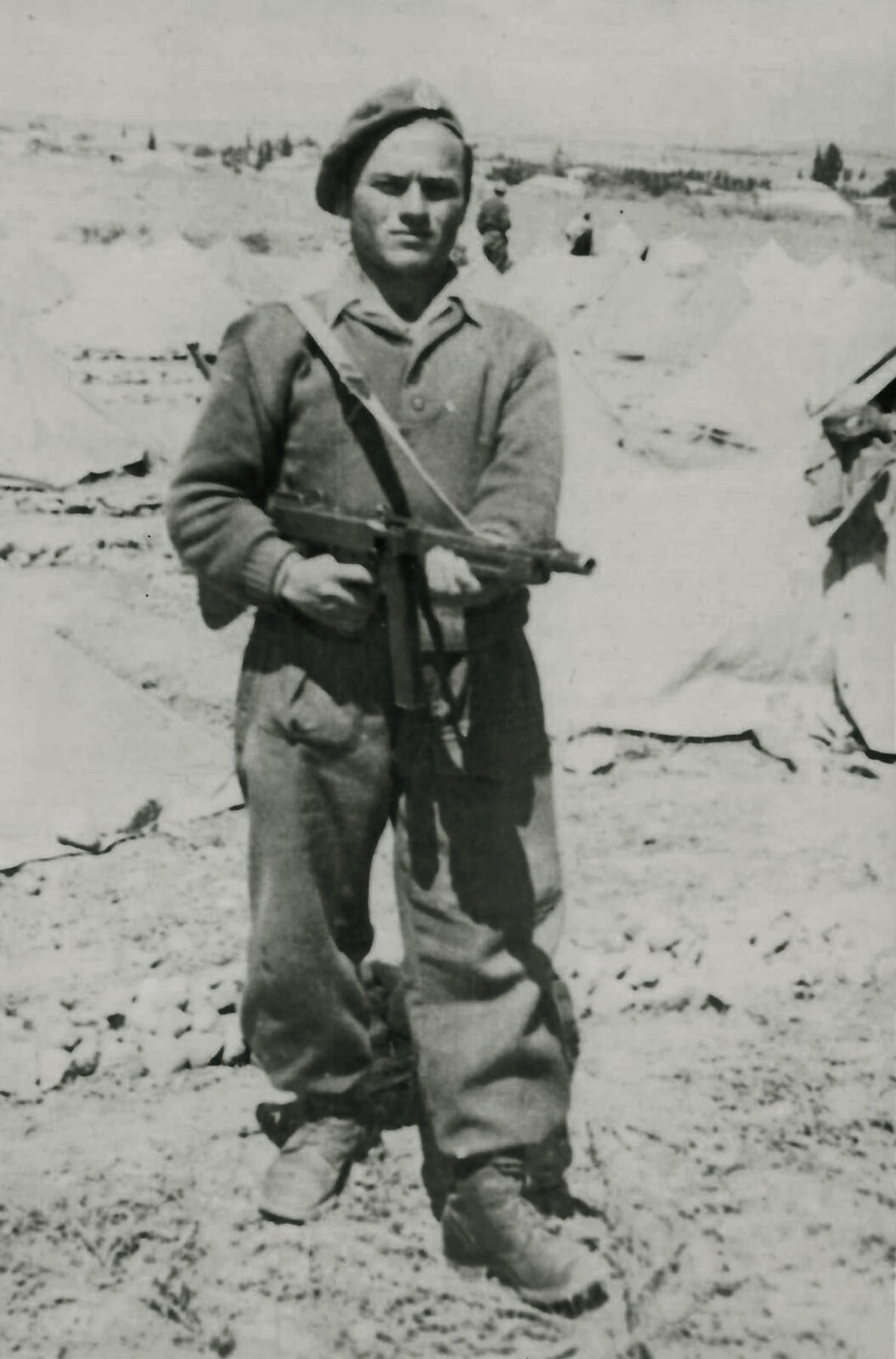

Harry during his military service in the early 1950s. Harry was relocated to the southern Peloponnese during this time. Photo: Supplied

Harry was born in 1924 in the Peloponnese village of Elekistra where he remained a shepherd for 38 years. He plausibly had no access to any formal literature or works of philosophy during the war, famine, poverty and political calamity in Greece at the time. As for many others, Australia was the promise of a better life. Representing some archaic version of Tinder, his future wife, Anastasia, chose his photo over that of a better-dressed rival and the shepherd-turned-bachelor was destined for Sydney aboard the Patris in 1962. Harry worked tirelessly at the steelworks to support his wife and three children, recounting hard yakka for bad pay and worse conditions. Epicurus sympathises that “no one seeks pain because it is pain, but because circumstances enable him to gain some great pleasure through toil”, such was Harry’s endurance of painful work.

Harry was austere in his early years as a Greek-Australian. Disciplined and taciturn; his character was a shopping cart of Stoic and Cynic values. He abstained from alcohol, coffee and dance, renouncing the social conventions of the Greek migrant. Thankfully, Anastasia’s extroversion balanced out Harry’s wistful unsociability. He fits Cicero’s description of a virtuous man and satisfies Aristotle’s condition that virtue is sustained by habit.

Cicero writes; “It is a peculiar characteristic of the wise man that he does nothing which he could regret, nothing against his will, but does everything honourably, consistently, seriously, and rightly; that he anticipates nothing as if it were bound to happen, is shocked by nothing when it does happen under the impression that its happening is unexpected and strange, refers everything to his own judgment, [and] stands by his own decisions. I can conceive of nothing which is happier than this”.

His Epicurean shift in later life seems inevitable. He’s earned his ataraxia and has a lot to celebrate. He rejoices in every meal and toasts to our health frequently. Of a long life filled with sacrifice, risk and hard work, Epicurus writes “blessed is not the young man but the old one who has lived honourably”.

In retirement, Harry operates with a calculated demeanour, selective and precise in his conduct as a response to his growing frailty. He starts his day at 5 am with coffee, whiskey and Vitaweats. He chimes into SBS World News and infers the day’s events from the proceeding French, Filipino and Italian telecasts. He comments on the varying perspectives of each telecast, contrasting their opinions and socioeconomic interests before consolidating his understanding of the day’s events with the Greek broadcast at 9:30. He routinely offers his solutions to the world’s problems, speaking acerbically in the same way I imagine Socrates delivered his criticisms of society.

Harry and Anastasia on their wedding day in 1962. Harry arrived from Greece in April and they were married in August, their children were born shortly after. Photo: Supplied

Harry with his wife Anastasia and their three children, George, Maria and Jenny in 1968. Photo: Supplied

Harry and his son George and daughter Jenny drinking coffee at Harry's home in Menai, NSW. Photo: Supplied

Harry and his daughter Jenny during a routine Saturday trip to the shops, May 2022. Photo: Supplied

The Greek news used to be preceded by 4 hours of gardening, but trips into the backyard are growing scarce in his old, old age. He has a Stoic indifference to the limitations of his body and does what he can, how he can and when he can without anguish. When he does meander to the garden, he spends as much time there as daylight offers. His crop is seasonal and informs most of his diet, it’s a lineup of usual suspects for a Greek backyard. Zucchini, eggplant, lemons, tomatoes, cucumbers, green beans, potatoes and cabbage under the shade of an olive tree twice as wise as its cultivator. Epicurus famously preferred a simple diet to an expensive one and writes “plain flavours produce pleasure equal to an expensive diet whenever all the pain of need has been removed”. One is empowered by living simply as their happiness is contingent on very little external to themselves. The solace of the garden means as much to Harry as it did to Epicurus.

Despite his unsociability, he values the atmosphere of the local RSL. He sits quietly nursing a beer and tapping his walking stick, contributing to the atmosphere as a sage observer. He observes families and groups and occasionally breaks his silence with an incredibly niche comment. Given the obscurity of his comments, I often doubt that he would socialise with strangers if he could speak English. But Harry understands the value of being in company despite seldom wanting to interact. Aristotle famously said that “humans are political animals”, and Harry acknowledges the importance of being around people and living in a polis (city). By the same token, he visits the shops every Saturday with my mum, a task he could easily offload but insists in the participation of.

I cannot be certain if I have merely elevated the pedestal upon which I place my grandfather, or if his practice truly reflects the culturally implicit nature of Hellenistic thought. Then and now, we always had the things we needed to be happy, we simply allowed ourselves to lose sight of them. I don’t blame us for looking everywhere else for a roadmap to a life well-lived, but the answers, written in virtue and tranquillity, are closer than we think.

“There is no way to live pleasantly without living wisely, honourably and justly, nor wisely, honourably and justly without living pleasantly”. This could be interpreted as a reflection of Harry’s conduct in 2022, or it could be interpreted as it was written, by Epicurus in 300BC. The difference is marginal, for if all these actions are descriptive of their actor, it would be impossible to differentiate the life of a man lived today from one lived 2300 years ago.

Alexi Piovano is a student of Journalism and Philosophy at the University of Sydney, set to begin an honours year focusing on Hellenistic philosophy.