One wintry Sunday afternoon, as we in Melbourne were enmeshed in the throes of the 2020 lockdown, my eldest daughter came to me and said: «Μπαμπά, όλο γράφεις και γράφεις αλλά ποτέ δεν γράφεις τίποτε για εμάς τα παιδιά».

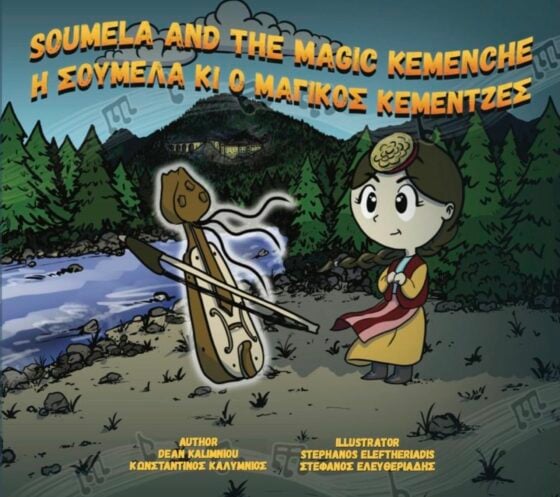

“Get some paper and a pencil and come and sit beside me,” I asked her. Over the following days, scribbling furiously, I would write a paragraph and read it out to my daughter. She would variously critique it, ask for clarifications, or suggest amendments of her own. In this way Soumela, the young girl from Pontus and her magic kemenche that sets her upon a remarkable adventure were born.

Soumela and the Magic Kemenche has its inception in our communal efforts to preserve the memory of and seek recognition of the genocide of the Greeks of Pontus. Over the years those efforts have as a by-product, produced interesting works of art. One of these was the locally produced 2008 film Pontos which was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. While viewing that film, I wondered what it would have been like to be a child witnessing the harrowing and brutal crimes of that era, for children are generally those whose voices are least likely to be heard. I considered that if I were a film-maker, I would like to tell the tale from the point of view of a young child by filming everything at knee height, that is through the eyes of the child, and with distorted voices giving the viewer a taste of just how enormous and bewildering the world of adults is to children at the best of times, heightening thus, the enormity of the betrayal when these adults fail to make that world a safe place for their progeny to thrive.

I am no film-maker but I dabble in music and have been enthralled by the Pontic lyra or kemenche, ever since childhood. In my youth, Pontiaki Estia had their clubrooms in close proximity to my neighbourhood and walking in with my parents one day to witness a lyrari expertly draw his bow across the strings, producing a sound both primal and yet infinitely complex, linear and yet three dimensional, I embarked upon a love affair with the kemenche which persists to the present day. I resolved that one day I would write a story about a kemenche that was possessed of magical properties. Throughout the years, I would revisit this motif, but somehow never found the time to broaden its scope so as to develop a coherent narrative.

At the same time, growing up, I devoured fairy tales of all description, from the Brothers Grimm, to Hans Christian Anderson and beyond. Yet the tales I enjoyed the most were those of Alexandros Papadiamantis and Andreas Karkavitsas, dark in a way that touched the soul and yet as familiar in psyche and ethos as the tales of hardship and despair my great-grandmother used to tell me. Growing up within a community of toilers who had seen terrible things during the war, lived a life of privation in their home country and were still struggling to establish roots in a foreign country, it was these tales that I could identify with the most. From my great-grandmother I learned that the Greek world for fairy tale, «παραμύθι» was traditionally a synonym for “consolation.” Our tales are therefore far from frivolous studies in superficiality. They are as dark and poignant as humanity itself and if they are to end “happily ever after,” this is only so as to provide the requisite consolation to go on, to persist in having faith in a world in which everything will go awry, until such time as we are old enough to navigate its tortuous twisting paths of fate ourselves. Paramythia, therefore, are an understudy of life itself, something that can often be missed by those brought up on a diet of Disney.

The conviction that whilst navigating the Greek and the western story-telling tradition as Greek-Australians, we were struggling to articulate our own authentic story-telling voice also informed the writing of Soumela and the Magic Kemenche. Indeed, finding the right voice to convey our stories to our children is a task fraught with difficulty. Modern Greek children’s writers such as Evgenios Trivizas have produced remarkable works that appeal to all ages. Nonetheless, we have sojourned in this country for over three generations. Our understanding of Greek culture and our traditions goes back to a time before the development of much of modern Greece and thus to slavishly copy the mores and modes of expression of Helladic literature is to alienate oneself from one’s own local identity. Similarly, Greek-Australian children’s writers who write in English often fall into the trap of presenting their narrative in a manner acceptable to or predetermined by the dominant culture, and by consequence, of treating the “Greek” elements in their story as exotic and foreign, instead of organic and thus, over-explaining. Having been brought up listening to the dulcet tones of Rena Frangioudaki narrating Greek fairy tales over community radio, in my mind hers was the most authentic voice to tell the tale and it is her voice that resounded in my mind as the narrative unfolded.

Upon his arrival in Australia, I was lucky enough to have a long conversation with Archbishop Makarios about the needs of children and their integral place within the Greek-Australian community, a place which I fervently believe, our community institutions have not always appreciated to the depth that they should. Conscious of the importance of children’s literature to the formation of a unique Greek identity grounded in the locales in which we live, Archbishop Makarios upon being presented with the text of Soumela and the Magic Kemenche, suggested that it be published by St Andrew’s Orthodox Press. He set two conditions: the first: that the story be bilingual and that the two texts appear side by side on the page.

“It doesn’t matter if there are children who cannot read the Greek text,” Archbishop Makarios remarked. “I want them in the least to be exposed to the Greek alphabet, to have visual contact with the Word.”

What resulted out of his suggestion are two parallel narratives that while similar, are not exactly the same, as the way one tells a story in Greek or in English is invariably informed by a myriad of cultural and linguistic factors that give each text a unique identity of its own.

The second of Archbishop Makarios’ suggestions was that a suitable illustrator be found to give life to the text. In his mind, this was the most important element in the production of a children’s book. As he put it, there needed to be communion between the author, the illustrator and the story so that the pictures could personify and subsume the text itself. In this regard, I could look no further than passionate Pontian and talented artist Stephanos Eleftheriadis, who has been grappling with similar problems of authentically portraying aspects of inherited tradition in a manner relevant to our place of abode, in the visual medium. The communion Archbishop Makarios spoke of was established the moment that Stephanos read the text. When I reviewed his preparatory sketches, I felt little Soumela come to life, exactly in the manner in which I had imagined her. Stephanos proceeded to illustrate the book with no direction from me. It was not needed. The incorporation of his drawings makes manifest the saying: “all that is uttered in words written in syllables is also proclaimed in the language of colours.”

Soumela and the Magic Kemenche works on many levels and can be read by people of all ages. For the young, it can operate simply as a tale of a young girl who embarks on an amazing metaphysical adventure. Older children and adults on the other hand can try their hands at unpicking the symbolism embedded within the text. Who is the mysterious person who helps Soumela on her way? What is the meaning of the message of the Magic Kemenche? Which psychological and metaphysical phenomena are best placed to assist us when faced with trauma? Where is Pontos and what happened to its people? Why does genocide take place? A discussion based on these final questions can be facilitated by reference to the resources provided at the end of the book, after the tale is concluded.

Soumela and the Magic Kemenche, from its conception, to its writing, illustration and publication could not have existed without the Greek community of Australia and its ancillary institutions, all of whom informed and supported the writing and dissemination of the book. Writer Denise O’ Hagan in her review of the book, deems it an “artefact which enables parents to carefully educate even their youngest children in their history, including its more confronting aspects.” Ultimately, in seeking to do so, the challenge is to tell our story in a sensitive manner that avoids inspiring hatred or rancour but instead instils in our young readers sympathy and compassion for all of those innocents who are victims of a world that would not be so cruel, if adults behaved themselves. It is for this reason, that the book is dedicated to all the mulberry stained children of the world.

*Soumela and the Magic Kemenche will be launched by educator Panayiota Stavridou on 29 May 2022 at 3pm at the Panacardian Brotherhood, 570 Victoria Street, North Melbourne. There will be activities for children and entry is free.