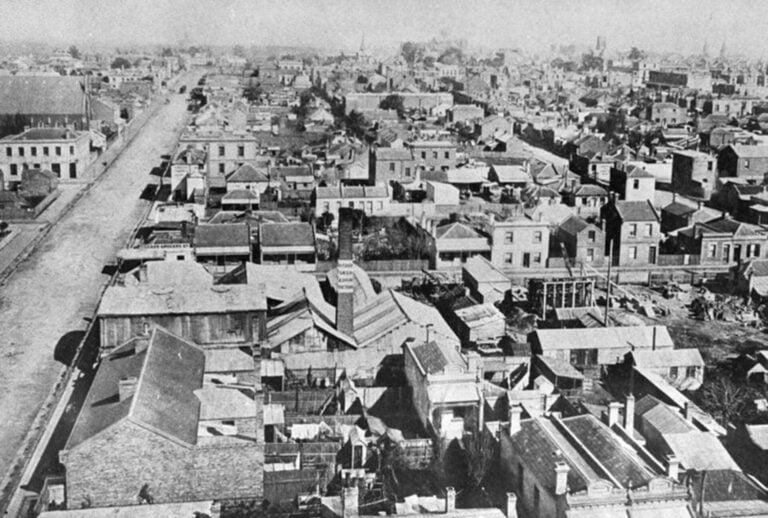

If you closed your eyes on Johnston Street in 1950s Fitzroy and listened you would think you were in the middle of Athens with the people rushing off to work, going to school or shopping all speaking Greek to each other. Between the 1950s and 1970s Melbourne inner-city suburbs like Fitzroy, Collingwood and Richmond were a magnet for Greek migrants who found work in the surrounding factories.

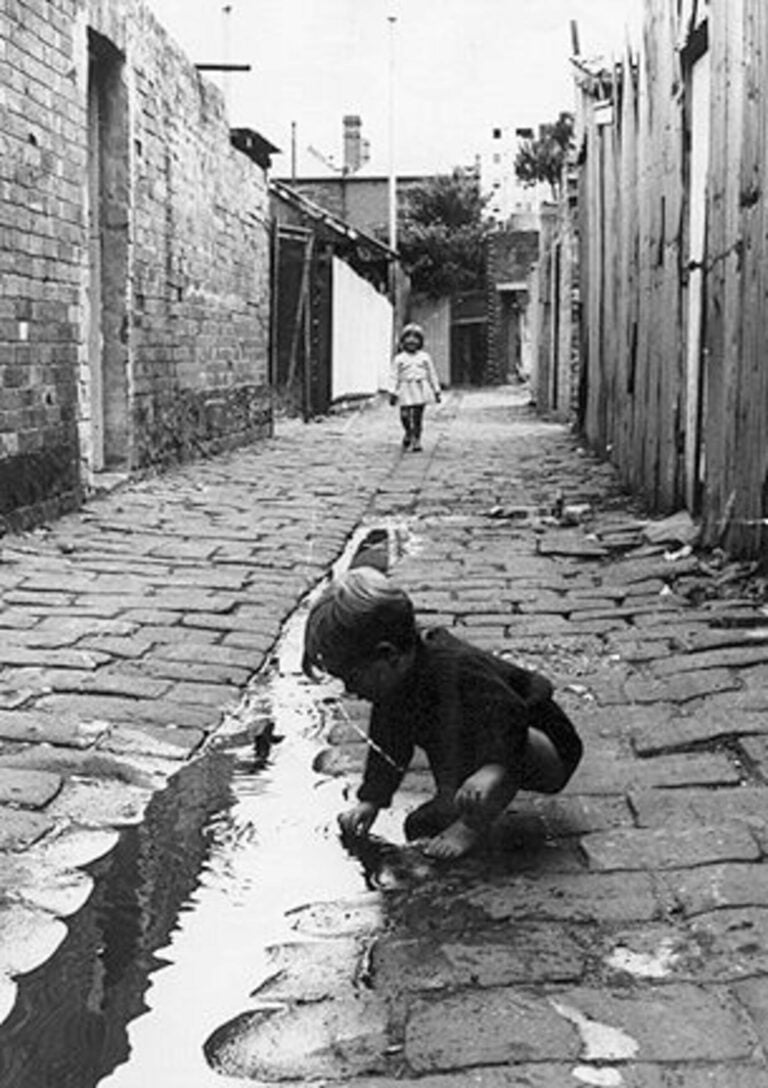

Professor Joy Damousi grew up in Fitzroy as a child, she played in its lanes and alleyways until the family moved to the newer more spacious housing of North Balwyn. Life has taken her a full circle now as the Head of the Australian Catholic University’s Department of Humanities and Social Sciences which is based in Fitzroy, now a gentrified, middle class suburb whose Victorian homes have been renovated and modernised.

Prof Damousi has given talks about the Fitzroy she grew up in, most recently as part of the ACU Game Day Lunch at the Community Room of Brunswick Street Oval last Saturday.

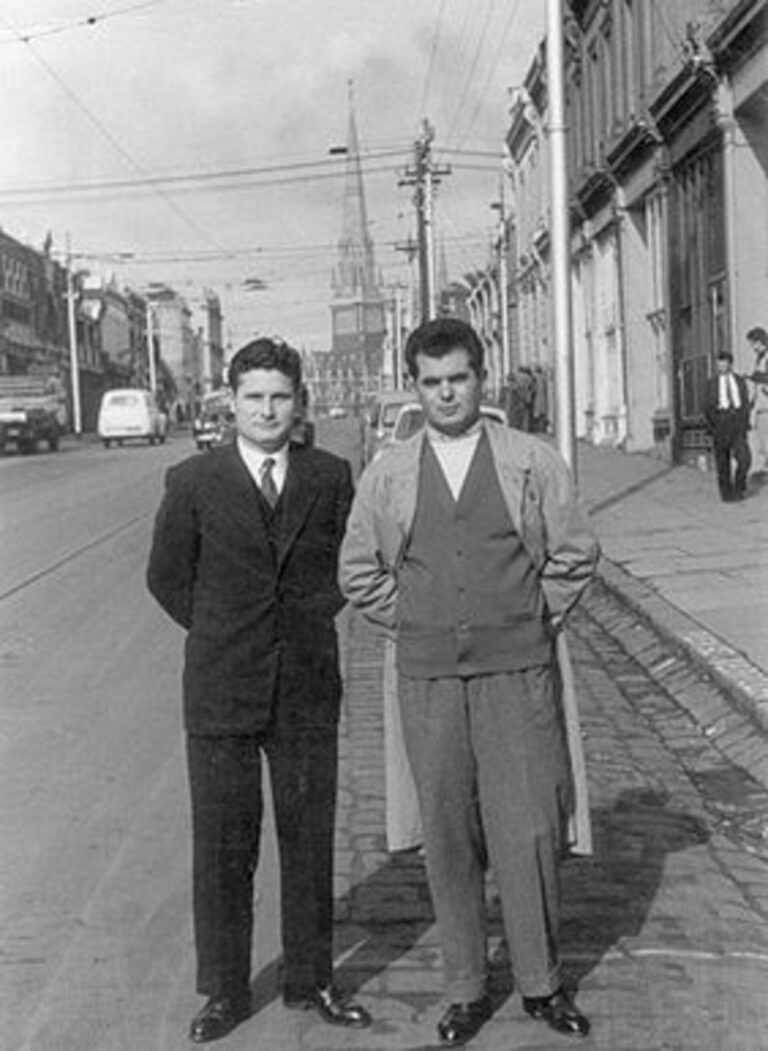

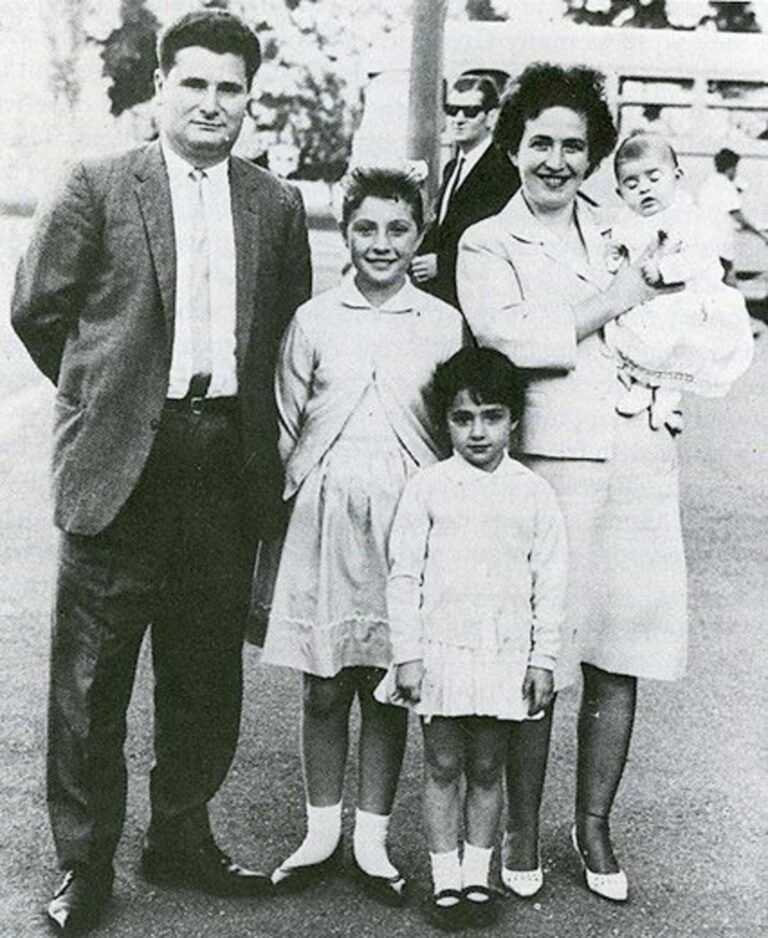

“We settled in Napier St, in a neighbourhood where there were many Greek families. A whole community of Greeks came to that area,” Prof Damousi told Neos Kosmos. Her father, George, who came to Australia in 1956 from Florina was a boot maker who found work in the Collingwood area the centre of boot-making since the late 19th Century. Her mum, Sophia, came in 1957 and she was to find work in the textile mills, mainly on Johnston Street. It was an industry that employed a lot of migrant women.

“The things I loved (about Fitzroy) were the lane ways and alleyways which were great for the kids to grow up in, roam around in the 1960s. We lived opposite a pub. It closed at 6pm and the patrons would come out drunk on to the streets,” she recalled.

“The area had quite a number of indigenous community families and old working-class families who had been there since the early 1920s. There were also working-class migrant Italians, Yugoslavs along with the Greeks.

“It was a real mix, a coming-together that was a foretaste of things to come in the re-shaping of Australia.”

One of the first signs of change was the type of food that was starting to appear in local shops. Shopkeepers began selling cans of olive and feta cheese.

“The real start in the shift (in society) was in being able to get food that you could not get elsewhere. It was only later that the kafenions and Greek restaurants began to appear. The first step was the food, “Prof Damousi said.

The kafenion life, which was the domain of the Greek male, developed around Napier and Gertrude Street.

“Women did not go there. Mum would often send me to get Dad for dinner and he would buy me an ice cream and let me play to delay leaving. The men would read the paper, discuss issues and talk about work – they would mostly be catching up with each other, much like Australian pubs.”

“The women went from home to home to socialise. They would spend the afternoons talking and do things together. We kids would be at home or play in the streets in gangs, playing marbles or footy.”

“I recall playing with the kids of working-class families who were not sure what to make of us, but there was no outright hostility. Their parents were polite but there was no embracing of cultures but towards the end of the 1960s some neighbours did mix. I remember particularly kind Australian neighbours who always gave us Christmas.”

The debate at the time was about would the migrants assimilate into society. Sport became the bridge for change. Many of the children grew to love Australian Rules Football which became the bridge between migrants and Australians.

“Sport was important. The main religion in Australia was Aussie Rules and it was a very important way into Australian culture. We played footy in the lanes, and as a woman and a migrant I grew to barrack for a team. In my case it was Collingwood, others settled for Carlton or Richmond.”

She also supported the local team, Fitzroy (now the Brisbane Lions), which did not do particularly well. While the game was a way into Australian life for the kids, it did not bring in the Greek adults who remained loyal to the round-ball version of football.

“My dad was always annoyed that we showed no allegiance to soccer and took much time explaining the superiority of the game. It was done in good humour but it was an interesting issue around integration.”

She said there was a concern that the Greek communities seemed to keep to themselves, sticking to their homes and their own churches and there was a concern that they were “ghettoising” themselves from the rest of Australian society.

“We (the children) grew up educated and became the bridge,” Prof Damousi said.

“I went to George Street State School (now Fitzroy Primary). There were big migrant classes learning to speak English because it was not spoken at home. I give a lot of credit to the teachers who taught us English and laid a good foundation for many of us to achieve our goals later in life.

“Classes were big, up to 30 children, the resources were limited and the teachers were not accustomed to working with such numbers.”

Where it was the kafenion on Saturdays, Sunday was for Church and the big focal point for the Greeks of Fitzroy and surrounding area was Evangelismos Greek Orthodox Church in East Melbourne.

“I was baptised there, it was central to growing up and was where the community gathered. It defined the Greek community.”

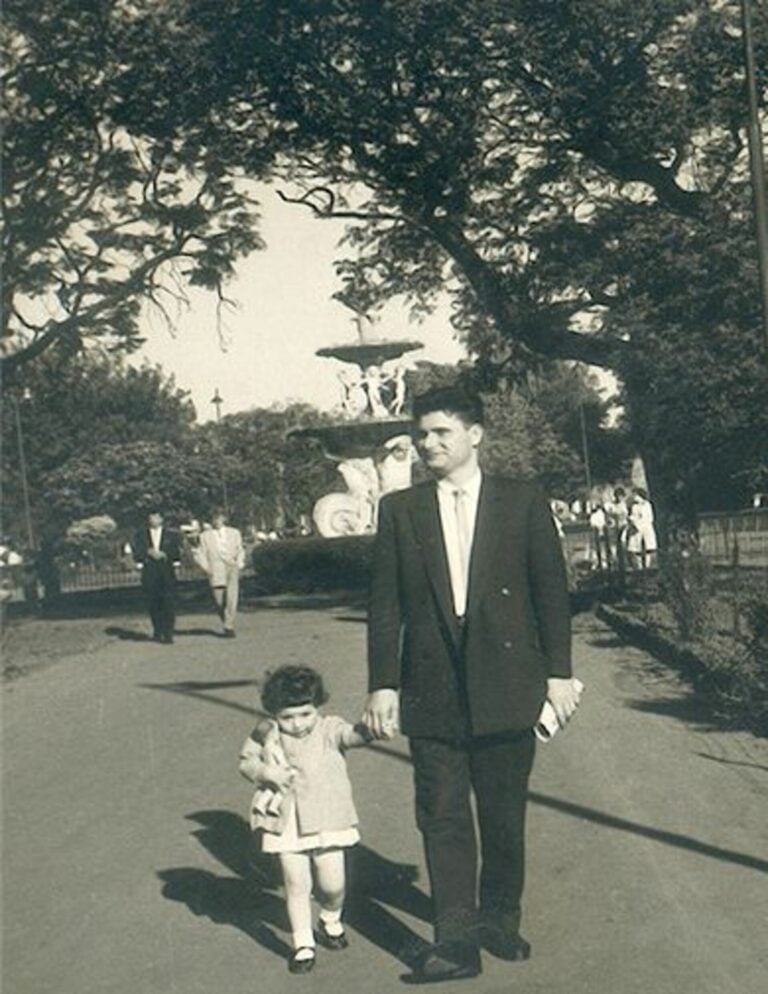

Another important place for the community were the Fitzroy gardens.

“We always went there for walks as a family as we had no backyard of our own. We would meet people and socialise there,” Prof Damousi said.

As the families established themselves economically, so did the need grow to get a bigger space with a backyard and garden. The 1970s saw many of the Greeks moving out of inner-city suburbs like Fitzroy for leafier more spacious living in eastern Melbourne suburbs like Balwyn North (where Prof Isogamous’ family moved in 1973), Doncaster, Oakleigh and Bulleen.

“They moved to suburbs with new housing and big backyards. These were closer to the dreams the migrants had (when coming to Australia) rather than the dilapidated Victorian homes of the inner-city suburbs. They wanted to be comfortable, they were aspirational and they were economically secure.”

Those concerns of whether the migrants of the time would assimilate are repeated with each new wave of migration, notes Prof Damousi. The same concerns were voiced when the Vietnamese communities settled in Australia in the late 1970s to Africans and Asians arrivals in more recent years.

“Eventually people relax on both sides. It happens with every new arrival, there is suspicion, and concerns that ease over time. Australia has become a more inclusive society towards its migrants.”