Time stands still, tranquillity, and peace engulf you. This is in Southern Italy where the remnants of an ancient Greek community continue to speak and live like a Greek, Calabria.

Not long most of Calabria spoke Greko. The people are mostly of ancient or Byzantine Greeks and the region’s topography is like that of Greece.

Magna Graecia, or “Greater Greece” in ancient and Byzantine times, is the are of Southern Italy once settled by Greeks and was reinforced by the Byzantine Greeks when Constantinople controlled South Italy until the eleventh century.

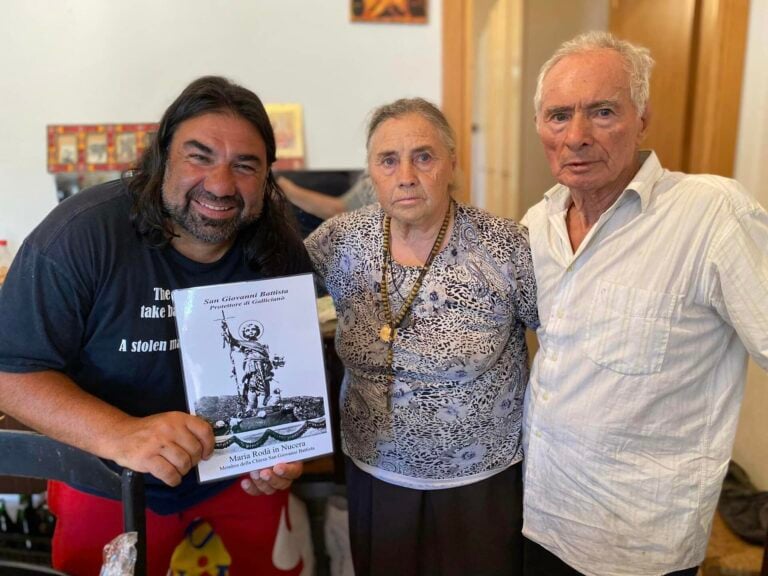

The descendants of Magna Graecia have a connection to the region dating back 2,700 years. The Greeks there dominated the economy, social and political life. They dominated commercially and had major achievements in mathematics, science and philosophy. In my recent historical novel, The Aegean Seven Take Back The Marbles, as I included chapters set in the south and specifically the town of Galliciano.

Galliciano (pronounced Gaddiciano) is as described by my friend Pantaleone Danilo Brancati, as “the Acropolis of Magna Graecia.”

The town is set on a mountain as you climb up a narrow, windy road from the National Highway, passing the dried up river in the Amendolea valley. The first time I came here was in 2002 with my friend, Carmelo Nucera and Pat Porpiglia. They showed me the then new Greek Orthodox Church – Panaghìa tis Elladas, and I met the key keeper, another Mr Nucera (popular surname), an amazing man and guardian of Greko culture, who I met again in 2022.

Four years earlier, Danilo, a musician, took my friend Basil Genimahaliotis and me to see the town as we w

ere shooting a series of documentaries in Magna Graecia. Aside from spending an hour playing music, we met a young Mimmo Nucera and his family.

We laughed, we ate at the taverna they specifically opened for us, and I purchased fresh cheese. Four years later I ate with his mum and family and once again sampled Greko made cheese. We talked, we philosophised and laughed. Just a typical day in Greece. But we were in Calabria at an authentic Greek town outside of Greece.

This may be the Acropolis of Magna Graecia, the people, perhaps 70 of them, are living ancient Greek statues. I feel transformed to another era whenever I hear them speak. I feel like I’m on Mt Olympus or my native Lesvos.

Greko is a language that speaks to the heart, imagination and passion of any Hellene. Another young Greko, Maria Olimpia Squillaci is one gifted. Her father taught and spoke to her in Greko and her family grew up speaking Greko in Bova Marina, a town where 15 percent speak Greko.

Bova Marina has a main street off the national highway which has a piazza, bars and also the one Greek restaurant outside of Galliciano – Mediterraneo. As is my tradition I had a nice Greek meal at Mediterraneo and met up with the owner Mr Salvatore Dieni and his daughter, who also speaks Greek. He runs a Greek cultural association, maintains a Greko library and welcomes Greek tourists annually.

The first time I came to Calabria, I arrived in Bova Marina, a town with a population of 4000. I was charmed by street names that appear in both Italian and Greek. It was here I met with former Condofuri local Carmello Nucera who is now based in Reggio, or rather word filtered around town that foreigners got lost, missed Rome and somehow ended up in Bova Marina, not exactly known for tourists. Word got around that I was looking for Greeks. Within an hour Carmello found us. He was the former Mayor of Vua, a smaller town with 800 people, but significantly, 400 Greko descendants.

Another person who met with me was local Greek teacher Philippo Violi who wrote a Greko dictionary. It was with great sadness that I learned that Mr Violi, a charismatic man had passed away . I was sad when Danilo told me that his mentor and well know musician and poet Mimmo Nucero Miliniari, whom I had met in Bova Marina with his grandson in 2018 when they played a concert for us in the Greko language. Danilo devastated and I felt the loss too. I knew that Francesca Tripodi had passed away two years ago, a poet and guardian of Greko culture from her time growing up in Roghudi.

The attention I receive on each visit to Bova Marina is similar to the “hysteria” reserved for someone big. Many are intrigued about how an Australian made a trip to the other side of the world in the hope of meeting Greeks. On the day I was catching up with Danilo for the first time in four years, I was at the hotel by the beach, wearing a shirt from Brasil. Suddenly I was swamped by a group of Brasilians led by Owerbeck Berlwinck. They were there to work for the summer and in the case of Owerbeck, he would move up the nearby mountain to Vua. The irony of randomly meeting Owerbeck and his mates at the forecourt of the hotel, it turns out that this is where I had met Carmelo and Philippo twenty years ago. The exact same date.

On the drive up some of the mountains including to Vua, many signposts that welcome visitors, in Greko, Italian and even in Modern Greek. I went to pick up Danilo on another day from Condofuri Marina, I passed Aristotle Street. Greko is rare, but the Greek spirit is not. At a coffee shop we had started chatting to some friends of Danilo with one of the lads having Greko heritage. I went to pay the bill. Soon though an “argument” broke out as to who should pay. I wanted to pay. Danilo wanted to pay. A stranger then wanted to pay. The barista probably didn’t want anyone to pay. We fought over who will pay, until the bill was paid.

Greko , dwindled in Calabria from the 16th Century. This was when the Vatican took control of Greek Orthodox Churches and the rite changed from Greek to Latin. As each century passed, hold-out monasteries and churches eventually succumbed to the Latin ways.

With each of those centuries, less and less towns spoke Greko as their first language. Calabria became a poorer and forgotten region, as did Greko. I was told by a younger Greko, Eleonora Petrulli, the Greko towns had dwindled by the start of the 20th Century. There was a sense of “shame” when people spoke the language in the valleys of Calabria as Italian superseded the Greko, a language of wealthier Italy. Eleonora reminisces how her grandmother sang to her in Greko to her when she was a child.

The Mussolini era saw an attack on minorities such as the Greko. Many Greko left Calabria or Italy in search of a better life. Once they left, few returned, and the numbers decreased further. Greko became an oral language not taught at schools, and spoken only in small villages and homes.

The 1973 landslides at old Roghudi saw the entire town relocated to the coast. Some moved to Melito, a big town where I met poet Bruno Stelitano on a visit with Maria Olympia a few years ago. Others were moved to the new Roghudi. I have been to the latter several times. It’s quiet and tranquil. Recently, I walked around and spoke to the residents with perhaps 10 per cent know Greko.

I visited the ghost town of old Roghudi with Pantaleone Danilo. We met a Greko grandmother who brought her grandson to see her old town in the heart of Calabria – a bittersweet experience for all of us.

Most of the houses remained, but the damage of time and neglect was evident. Time had stood still. I remember in Costa Vertzayias’ 1990 Magna Graecia book there was a lone woodcutter who refused to leave and may have passed away in the 2000s. A Greek monk was rumoured to have lived in the mountains at this time. The river is dry in the warmer months and the elevation of the homes should be enough to withstand all but a return of Noah.

Danilo is the president of To Ddomadi Greko, an association made up of younger Greko in the Greko towns. They hold annual workshops for people from abroad and they work hard to support the language. If you do one thing next year, I encourage you to reach out to these young people to help them support the Greko language.

In Reggio, Carmelo Nucera is the heartbeat of the impressive and very active Circolo culturale APODIAFAZZI along with people such as Valeria Maria Genua.

Those who have remained remarkably committed to the preservation of the Greko culture should secure support from Greeks abroad. We have one Acropolis in Athens which is preserved, lets preserve the other Acropolis in Magna Graecia.

The film Magna Graecia the Greko of Calabria is screening on Sunday 13 November at 6 pm, a presentation by AHEPA NSW. Bookings: Chapter Antigone President Charoulla on 0411 137 266 or info@ahepansw.org.au. Prices: $19 for adults and $15 for concessions. Note, the event is MC’d by Themi Kallos from SBS Radio and the QnA is hosted by Calabrian heritage actress Belinda Maree.

Billy Cotsis is the author of The Aegean Seven Take Back The Stolen Marbles