“My old friend, what are you looking for?

After years abroad you’ve come back

with images you’ve nourished

under foreign skies

far from you own country.”

-George Seferis ‘The return of the exile’

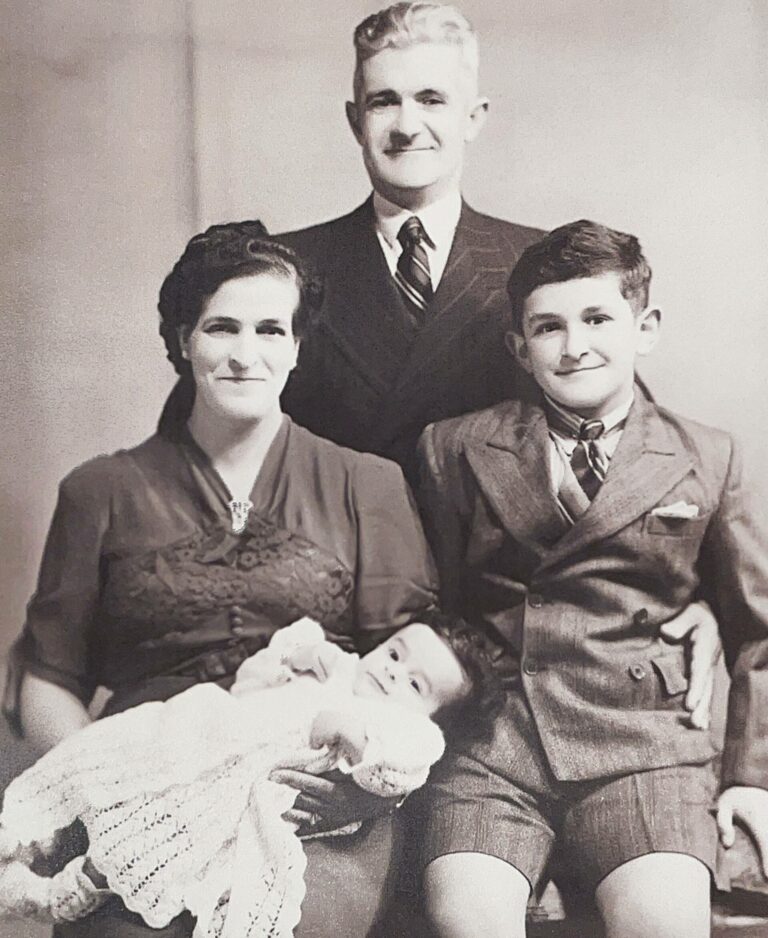

On Sunday, 4 November 1923, Andreas Manos disembarked in Station Pier, Port Melbourne. He was born 17 August 1896 in Vourla, Asia Minor, (now Turkey). Manos exhaled his last breath in his city, Melbourne, Christmas Eve 1996, just shy of a century since his arrival.

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919 to 1922 turned Manos’ world to ash. He was just one of the two million Greeks expelled from their ancestral homelands at the tip of a bayonet, and muzzle of a gun. He escaped, over 250,000 died, many on death marches led by Turkish military and irregulars.

Like most of his fellow refugees, Manos first fled to Athens. Seeking better opportuities, he then went to Alexandria in Egypt, and finally Australia. Greece was broken after its catastrophic war which made Manos a refugee and a citizen of migration.

Australia offered peace, and opportunity, to those fleeing the dark storms amassing across Europe and the Middle East. As 1963 Nobel Laureate, George Seferis, himself an Asia Minor refugee put it, Manos made a new life ‘under foreign skies’.

The “palikari from Vourla”, (lad from Vourla), as he was known, worked hard and sought opportunities.Toil was at the centre of Manos’ life. He left school to work for the family farm and kept working untill old age.

Manos’ century defined by great watersheds, great catastrophes and great opportunities. The Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 sealed the fate of the ‘Sick Man of Europe’ the crumpling Ottoman Empire which reigned over Greece, the Balkans and the Middle East since the mid 1400s.

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22 was a major military failure for Greece. It resulted in the Great Catastrophe, defined by the burning of the city of Smyrna (Izmir), and expulsion of two-million Greeks from the new Republic of Turkey.

When Manos arrived in Melbourne, a nascent Greek community numbered a few thousand throughout Australia. Mass chain migration of Greeks began after the end of World War II, when the Intergovernmental Committee for Migration from Europe (ICME) was set up, and a bilateral agreement was signed between Greece and Australia in 1952.

Melbourne in 1923 was a far cry from the modern multiculural urbane city it is now. Near the Flinders Street train station were the fish markets, where Manos went every morning from 4am. Street-gangs and gangsters like “Squizzy” Taylor menaced Collingwood, then a working-class neighbourhood, not the gentrified hipster suburb of today.

Life in Asia Minor

Manos son Stefanos (Steve Manos) says that his father was one of seven siblings born to Katina, originally from Kythera and Stephanos from Naxos. Both lived over 100 years.

“In Vourla he went to the same school as the poet George Seferis, my father had to give up his education when he was only 11 to help his family in the fields.”

Steve Manos is known for his community leadership and as a member of Australian Hellenic Educational Progressive Association or AHEPA. He says about 30,000 Greeks lived in Vourla before the Great Catastrophe.

The city was an economic, cultural and educational hub. The Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Anaxagoras set up the Anaxagorean School there around 400 BC. Greeks and Turks had their own districts, with a stream dividing them but says Andreas Manos, “life was generally peaceful.”

“However, there were periods of tension and people sometimes disappeared.”

“My father worked with animals, and on the fields, but as soon as he heard about the Greco-Turkish War he volunteered for the Greek Army.

“In 1919 he was 23 years old and he fought in the front, in Afyonkarahisar and Eskişehir. Being fluent in Turkish he acted as the interpreter for the sergeant-major of the renowned General Nikolaos Plastiras”, his son says.

Steve Manos laughs when relaying stories his father told them.

“One night, he snuck out, unauthorised, to go back to Vourla and attend to newborn calves (sheep). When he returned the next day he missed the morning roll call.

“He expected to be courtmartialed and was sent to the captain, but he explained that his father was old and needed help to deliver the newborn calves, the captain spared him.”

On the front he saw action with to Georgios Foufoulas, his sister’s Vasiliki husband, parents of Greek Australian, Kostas Foufoulas, who assisted by invited by his uncle Andreas Manos, migrated to Australia in 1953,

“In the Battle of Sakarya a missile lodged in my father’s hip, and he was transferred by carriage first to Bursa, Mudanya and then to an Athens military hospital.”

“He told his mother in a letter, that he had scabies, rather than upset her by telling her that he was wounded. ‘When they discharge me from here I will come and find you,’ he wrote.”

First a refugee and then an immigrant

Those like Manos’ family who survived and forced lost everything. Whatever property they had was either burned or stolen. They left with nothing. In Athens as refugees they lived in tiny house in Polygono.

Andreas initially worked in a dairy store and there he saved enough for a passage to Alexandria – which was then a cosmopolitan city with a large and ancient Greek community.

“My father went to the Averoff Gymnasium to look for work. Vassiliadis, who was the general manager, gave him a job as a caretaker.

Manos was restless, never content but always enterprising.

“He bought oranges in bulk, at the cost of a penny a piece, and employed a woman to sell them on the street for two,” his son, Steve Manos says.

He raised the money for a ticket to America but was unsure.

“Mother, don’t write to me because I don’t know where I’m going. When I get there, I will write you” he wrote.

In Alexandria he met George Nikakis who had an uncle in Sydney and was leaving for Australia. Manos hardly knew where Australia was on the map, yet decided to follow Nikakis.

They spent 39 days on the Italian Caprera and Steve Manos says; “They ate spaghetti, for breakfast, lunch and dinner and there was no mention of English lessons, that were later offered on the [ocean liner] Patris” which brought thousands of Greeks to Australia, Steve Manos says.

“Somehow my father found out some fellow townsfolk from Vourla lived in Melbourne, the Heliotis family.”

“So he began to search for them, on a strange city, he cut pieces off a newspaper then leave them in certain places as a trail, to find his way back to the port, if something went wrong.”

His father headed to the Panhellenic Association Orpheus located above the Tivoli, on Bourke Street “there were where rooms for Asia Minor refugees, ‘The Pharos (lighthouse) of Constantinople” Steve Manos says.

“Antonis Heliotis who owned a shop downstairs told my father that his sister Archontia had a house in South Melbourne, and rented rooms out, he said, ‘when you get a job, we can discuss rent.”

Manos began as a cook at £2 a week, but had no idea about either cooking, and no English skills.

“Lucky it was Australian food, eggs, sausages, bacon, beans – simple, and my father also worked under a Swedish chef, François who helped him to learn.”

“He was there for nine years, and became a great cook. Suppliers of meat meat, eggs, vegetables, began to bring extra for him to take home.

“My father ate at the restaurant, and he didn’t need anything, whatever the suppliers gave him he then passed on to Archontia. Eventually, he was best man at her wedding, and after became godefather to her two children,” explains his son.

His marriage to Despina Lyritzis from Alatsata

Andreas Manos married Despina Lyritzis whose family were also refugeesfrom Alatsata in Asia Minor, a Greek town before the Great Catastrophe.

According to Steve Manos, the Lyritzis family had a last minute escape from sure death.

“Despina’s younger brother Evangelos climbed atop a hill and spotted smoke rise from burning towns in the distance.”

He says that they packed up and ran for the beach and hid for three days in fear of Turkish militia finding them and killing them. They hid until men from the neighbouring island of Chios arrived with their boats to rescue them.”

“Before they lost their homeland, one of the children, Kostas had left for America by the end of the 1920s, but the rest of the family, apart from my his father George who died of grief, landed in Melbourne.”

“My father wanted a girl from Asia Minor, he met my mother through Archontia, who knew the Lyritzis family.”

His grandson Kostas Foufoulas remembers how his grandfather Stefanos Mandraos told his son – Andreas, he’d saved enough money by the early 1930s to return to Greece and reunite with his parents Katina, and Stefanos, and siblings,George, Nikos, Vasiliki, Evangelia, Chrysa, Maria”.

“He packed a baoulo (trunk) and wrote a letter to his father, ‘Dad I’m getting ready to come home.’

The response was ‘Son don’t think about it, stay where you are, things are bad here’ his father replied.”

In July 1934 Manos married Despina Lyritzis at the Holy Church of the Annunciation in MelbourneThirteen years since Andreas Manos was almost killed in the Battle of Sakarya .

Certificate of Marriage in English.

Certificate of marriage in Greek.

The ticket with the Italian boat Caprera.

Andreas Manos' military records in 1922. His surname was Mandraos before he changed it in Australia.

Hard work and progress

He worked hard, seven days a week, morning to night. Manos moved from worker, to owner, he bought a store, then a fish & chips shop, milk bar and a sandwich shop.

His sons Steve and George were sent to an elite private schools, with education as a primary focus, like most migrants.

“My father woke 4am for the fish market. He didn’t know how to drive, so he’d wait for a fisherman to pick him up.

“The fish market had a fountain inside so you’d purchase fish and clean it there,” Steve says.

“Collingwood was poor at the time and my father helped anyone in need, especially little kids who had nothing to eat.”

Foufoulas remembers after the Greek Civil War (1945-1949) ended his uncle Andreas “sent parcels, one after the other, we wore rags.”

“No more than 11 litre boxes were allowed back then, 5.5kg, and I remember going to the post office with 5-6 parcels at a time,” Steve Manos says.

He befriended a police officer called Bullock, and often invited him for a meal. In terurn, Bullock gave him a whip for protection against Collingwood’s gangs and gangsters .

“There were gangsters in Collingwood. Lots of stabbings. They worked in factories making shoes, boots, slippers. Most of the workers carried a curved knife, and with it they fought each other.

“They were broke mostly, they never had money. My father would note down the meals they had and by the end of the week, when they received their pay check they would pay up, not without a few incidents.

Bullock was the one who told him to change his name from Mandraos to Mandros, then Manos.

Greece 30 years later

In 1953 Andreas Manos returned to Greece it was 30 years since he migrated.

“My mother was obsessed with gold pounds and put some 200 aside and told my father to take them to his family.”

“My father was worried about travelling with the money, but my mother, a seamstress, took one of his heavy coats, unstitched the collar, sewed the gold coins into the lining.”.

“When he arrived in Greece, it was summer and he was sweating, the officer at customs asked him why he was wearing the coat. He said, ‘Listen, son, I come from a cold climate and I get cold, so let me go…’.lucky they didn’t have metal detectors in those days,” he laughs.

“When he arrived home he told his mother to get him a pair of scissors, tore the lining Mrs Katina was dumbfounded.”

“He missed his father Stefanos who died three days before he arrived”, his nephew Kostas Foufoulas, then 18 and had his papers ready for Australia.

“I asked, ‘Uncle when am I leaving?’ He said ‘we will leave together. I saw them and they saw me. I also have my family; my work and I am not letting you make such a long journey alone’.”

Life in Australia

Kostas Foufoulas is one of the 26 people Andreas Manos assisted to migrate to Australia.

“After his visit to Greece in 1953 my father returned again in 1958 and in 1973. That was the last time he saw his family there…”

It was in 1958 that he bought a milk bar in Caulfield. Yasemi was also close by and his two children.

“In the evenings, when my father would go rest, George and I cleaned up, filled the fridges and closed the shop, so that my father would find it ready in the morning.”

“He reached over 90 years and still worked, he used to carry the crates full of bottles all by himself, he didn’t smoke, he didn’t drink, he didn’t gamble. He had only two passions, home and family, here and Greece. For him work was entertainment.”

Steve Manos recalls an incident at the Holy Church of “The Annunciation of Our Lady”, when he was a child. After the service the priest announced that there was a couple who wanted to baptise their baby, but could not find a godfather.

“My father raised his hand. We stayed back, they filled the basin and baptised the baby, got into a taxi and came home. It was Sunday lunch, they sat down, ate… they were now koumbaroi (in-laws)

But a short time later they packed up and left for Greece. We never saw them again…”.

Tears roll down Steve Manos’ eyes when he talks his father’s story.

“He made us love everything Greek even though we were born here, we learned Greek thanks to him. He was strict, if we spoke English he wouldn’t respond. From the day I was born, April 9, 1935 until I started primary school, I didn’t speak a word of English. My Lyritzis grandmother, used to sing a little song in Greek: ‘Soup in the evening, soup at noon, soup every day, holiday, winter summer…’ I still remember it.”

“He has the devil’s memory”, his cousin Kostas Foufoulas jumps in, “Just like Uncle Andreas.”

The “Return of the Exile”

Andreas Manos returned to Greece three times from 1923 to 1996. Like hundreds of thousands of Greeks, he was both a refugee and an immigrant. A pioneering migrant Andreas Manos laid foundation stones for Melbourne’s Greek community and paved the way for hundreds of thousands Greeks – after World War II .

He never met his childhood acquaintance poet and Nobel Laureate, George Seferis also a refugee.

Refugees unite by longing and vivid memories of a lost homeland. Seferis expressed that in his poetry and Manos with an incredible resilience and a positive attitude to life.

In Australia, the ‘tyranny of distance’ was very real in his time, and near impossible to maintain contact with Greece, yet he still managed to instil in his family the love for Hellenism, but Andreas Manos never returned to his birthplace Vourla.

His sons Steve and George, and grandson Andreas did make the journey back -Seferis’ poem The Return of the Exile-lives in their hearts.