It has been 62 years since Ioanna Gendis (née Paziou) set foot in Australia to reunite with her first love. Yet, memories of the Greek Civil War – in the mountains of Evritania – are ghosts that continue to haunt her.

She still grieves for the peaceful family life she lost forever at a tender agAs she recounts those years to Neos Kosmos, what stands out vividly is the unexpected kindness of strangers in moments of desperation, but also how cruel and inhumane others were during the bloody fratricide.

Her childhood came to an abrupt end one winter morning in 1948 when she was ten years old. It was the day, her whole family, was forced to abandon their home in the small village of Topoliana and flee to the mountains for safety as the Civil War raged.

The war arrives

Her father, Nikos Pazios, was the village grocer which allowed him to stay informed with the latest news, as he interacted with individuals from both the left and the right, Ioanna says. Regardless of whether visitors to their village were partisans, or Greek army soldiers, her family welcomed them into their home.

“But he finally got caught up in it. They got him involved.” Ioanna believes that the family’s fate was sealed when her father tried to warn his brother-in-law in Valtos, from the village across the river of Aheloos, to go into hiding before the rebels came through. This led some to assume that for him to know the movements of the partisans, he must be in league with them.

“There were some people in that village who would not hesitate to kill, and the truth is that they forced my dad to take us and leave. If we had gone down to Agrinio, Lamia, or Athens, we might have been okay, but they would have definitely killed my dad. So he was forced to join the other side.”

“I will never forget the day we left the village and I don’t think any of us will, except for Maria who was very young. I remember when I woke up that day, there was chaos in the house. I saw my mother in tears packing our belongings, and my dad emptying the house, taking things to shelters, and I knew something was terribly wrong. My mother tried to reassure me that we would better off in another village, but something inside me froze. ‘How can we leave our home, our things? How can we leave?’ I kept asking.”

Her childhood until that day was carefree and although war raged across Greece, the small mountain village in Agrafa where she grew up had never felt the war.

“We were very high up, I don’t think the Germans ever got that far during World War II.” Apart from the school which was often closed due to the war, the only thing she remembers differently from those years was that her mum used to bake unsalted bread. Her father often went down to Agrinio, Karpenisi, Amfilochia to exchange products. “He would take honey, butter, cheese and return with salt, pepper, raisins, figs, products that we didn’t have. Salt in those years was hard to find.”

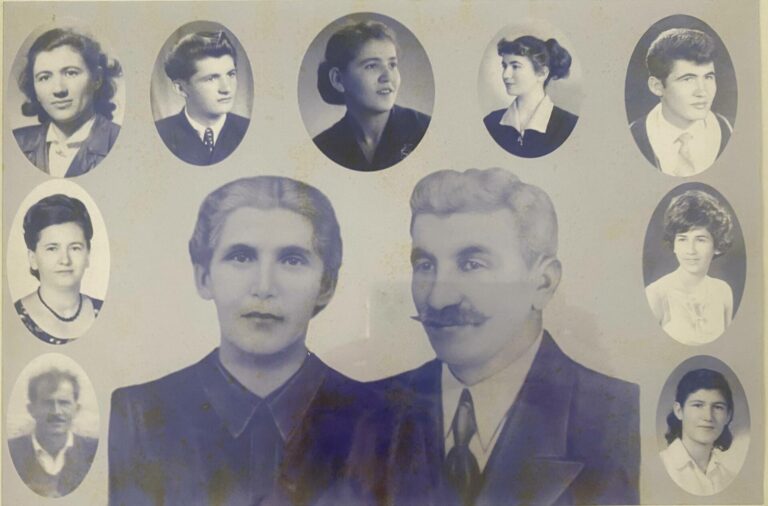

“We were a big family; Our parents, and nine brothers and sisters. There was a lot of love and warmth in our home. I don’t remember us ever being hungry, cold or deprived of anything. And now that I’m older, I often wonder how those two people managed to make us feel so carefree, so loved.”

On the run and starving

Unlike most villages in Greece, the women in Topoliana didn’t work in the fields, so Ioanna’s mum took care of the house, the children, the food, with her older daughters’ help.

“I don’t think my father was a communist, but he was a democrat. He hated fascism and injustice”, Ioanna says. She remembers the days and nights in hiding in the mountains, villages, caves and the countryside exposed to the cold, feeling the sharp pangs of hunger, and living in fear for their lives.

Their goal was to cross the border with Yugoslavia and from there to head to one of the soviet states. But the border was closed and the family remained stranded in the mountains.

“It was February, snowing and bitterly cold. First we went to Limeri, a village nearby, where we stayed for a couple of weeks, and then to Megalo Horio, and the villages around there.” They spent time in Viniani, where the children attended school, but when the National Army intensified operations to clear out the partisans, they had to make a run for it again.

“Dad knew what would happen, so we had to leave again. He took us up some mountains, when it was heavily snowing . We were little, and very cold, we didn’t have warm clothes…no coats, nothing warm. Dad cut branches from fir trees, laid them down, and the five of us (the youngest), lay down next to each other and he covered us again with branches to sleep. We warmed up next to the other, but it snowed so heavily that in the morning they couldn’t find us” Ioanna laughs.

“We had nothing to eat. We searched for wild potatoes, unripe apples… we ate them. The children we looked on the ground for koukousoules – something that looked like small potatoes, we ate them, and they were nice. Whatever we found that wasn’t bitter we ate.”

When they reached Granitsa, closer to their village, they hid in a cave.

“It was raining and along with the rain rocks fell from the mountain. As they crashed, sparks flew like fire, and we were frightened. From there we went up a hill to a little hut and in that hut there were 20 of us… All day long we were in there, and at night, mum would cover the hut with blankets to light a fire. All she had was flour. She’d get snow, put it in the pot, light the fire and add the flour to make a porridge. That porridge I couldn’t eat. ‘Say it has milk, say it has sugar,’ my poor mother would plead with me. We had a hen with us… whose presence in the end gave us away.”

Since there was no way to get Ioanna to eat that porridge, her mother would feed it to the hen to lay an egg.

“Every fortnight the hen laid an egg and I survived on that for two months. I started to turn blue. When the fighting subsided and we went down into a village, we found potatoes and my poor mother boiled them and the first potato she gave to me. But my throat had closed and I couldn’t eat. She had to mash it with water and feed it to me.”

“Those years were so tragic. And we couldn’t even understand why we were there.”

Family torn apart

On the night they arrived back to their village, the family was altogether -except for the two eldest, Socrates who was wounded, and Lena who was still in the mountains. In the morning when her father walked out of the hut at the edge of Topoliana where they were hiding, he saw soldiers swarm the hills surrounding them.

“‘Argyro, I must go. They will not do anything to you and the children. But I must go’, he told my mother. And my sister Koula, who was then 18-19 years old, fled with him, and so did Kostakis, who was 15. That morning we parted. The whole family was never together again. Ever.”

“When the soldiers reached the hut they lifted their guns and called for us to surrender. My poor mum put up her hands and said ‘I surrender’ but her voice was so weak you could hardly hear her. We laughed because we thought the whole thing was funny and mum pleaded with us to stop, fearing that they would kill us. We continued to giggle… we were kids. The army came in… they didn’t harm us. They took us to the school in our village. Our home was still standing. It had not been burnt down yet by supporters of the extreme right.”

It was the Spring of 1949. At the school, an officer with a cane and a slice of bread with jam, questioned little Ioanna about the guerrillas they met and how they got on.

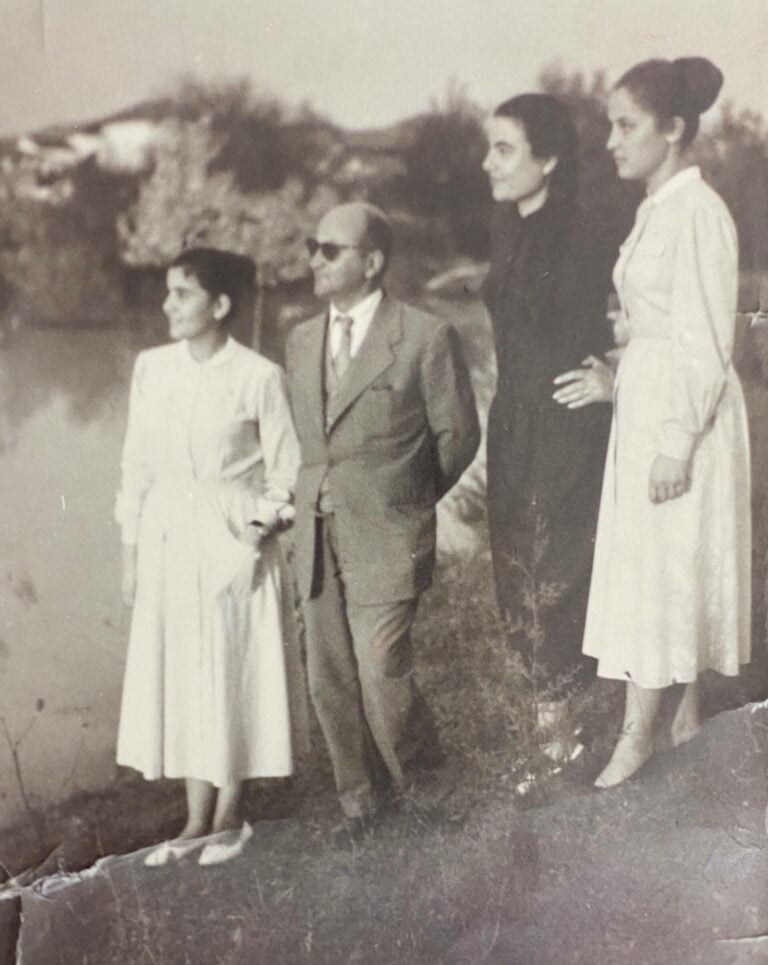

“The next day we were taken from Topoliana to Empesos, near Amphilochia. We walked for seven hours. There were a couple of other families too, my mum and us five kids who remained with her; Aliki, George, Angeliki, Maria and I. When we got to Empeso they left us outside a kafeneio. People would come to look at us, just like the circus. They stared at us but didn’t approach. Some said ‘they are communists’, others ‘they are criminals’. But there was a priest who lived on the outskirts of this village, who came and asked the police and the soldiers if he could take us to his house. And they let him. His daughter gave us all a bath. She made us eggs that we hadn’t eaten in so long and warm bread.

I’ll never forget their kindness. I remember this all my life. I said there were good people in the world. I never forgot that man. The courage he had to take five kids and my mum, to feed us and put us up for the night in his house…”

Mother imprisoned

The next day they were taken to Agrinio where another heartbreaking separation loomed.

“I will never forget that night, when we were separated from our mother as she was taken to prison. I remember Maria, who was only four at the time, trying to in between the soldiers’ legs crying for her mother. My poor mother… to be separated from her children. We didn’t see her for months…”

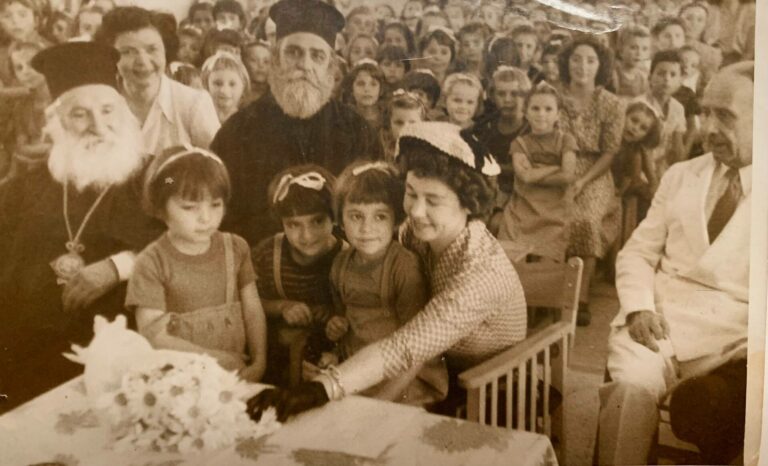

The five children were taken to a children’s home in Agrinio (children’s homes were institutions created during that time, known as Paedoupolis) before they were transferred. A few months later, the girls settled in the Paedopolis of Larissa, and her brother at Ziro, a few kilometres from Filippiada.

“They bathed us, cut our hair, gave us clothes, shoes… The night I slept there for the first time, I felt such a relief. I couldn’t have imagined that I would sleep in a bed again, that I would be so rested after all we suffered, the snow, the hunger, the fear. They looked after us, they educated us. I lived there for ten years…”

Her concern for her mother though, weighed heavily on her, and she could not find peace.

“We were still in Agrinio when they brought my mum to see us, as they planned to send her into exile. When the officer brought her to us, we all held onto each other and begged them to let her stay, so we can see her. A relative came forward and said that my mother was not to blame for anything and that he would take care of her himself.”

Return to ashes

After a few months they released her and she returned to the village where nothing of theirs was left. The house was burnt down and there was not even a fork to eat the wild greens she picked.

“But then, there was a miracle waiting for her too,” Ioanna smiles. When they had abandoned the village, they took with them some sheep and their dog. “This dog, our Turka, never left us. At Sarantaporo though, during intense battles we were forced to abandon them. Many months later, when our mother returned to the village, she found our Turka with these sheep. The dog brought them back all the way from the borders to their stables in Topoliana, and when he saw my mum he went crazy with joy. With these sheep, my mother started to build her life again.”

Meanwhile, Ioanna was nearing her 14th birthday when the principal of the Paedopolis invited her to decide about her future. Having seen nurses of the Red Cross treating the wounded rebels in the mountains, Ioanna knew that she wanted to become a nurse, but more than anything she wanted to work so she could help her mother.

She discussed her request with Queen Frederica, who happened to visit the Paedopolis at the time, and showed an interest. She suggested that Ioanna work in the Infirmary where she would also learn the profession. The money she earned she sent directly to her mother and she in turn rebuilt their family home brick-by-brick.

“That’s why my mum would often tell me, ‘Ioanna, you are not my daughter, you are my mother, you are everything’.”

Six years went by before she saw her mother again, when she came to visit them, and she could hardly recognise her. Her father, who had fled with two of the children to Poland, returned to Greece ten years later. After prison and the court-case, he too went back to the village. Of the nine brothers and sisters, only three returned to live in Topoliana; Socrates, Koula and Lena.

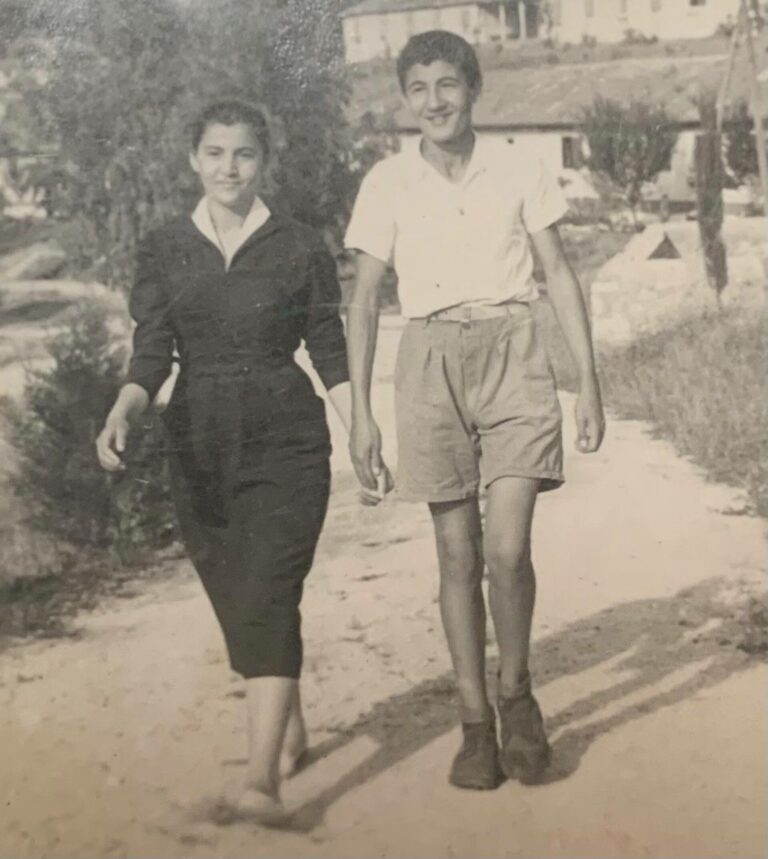

Ioanna visited her village for the first time since the traumatic events, when her sister, Lena, was getting married, and everything seemed different.

A new direction

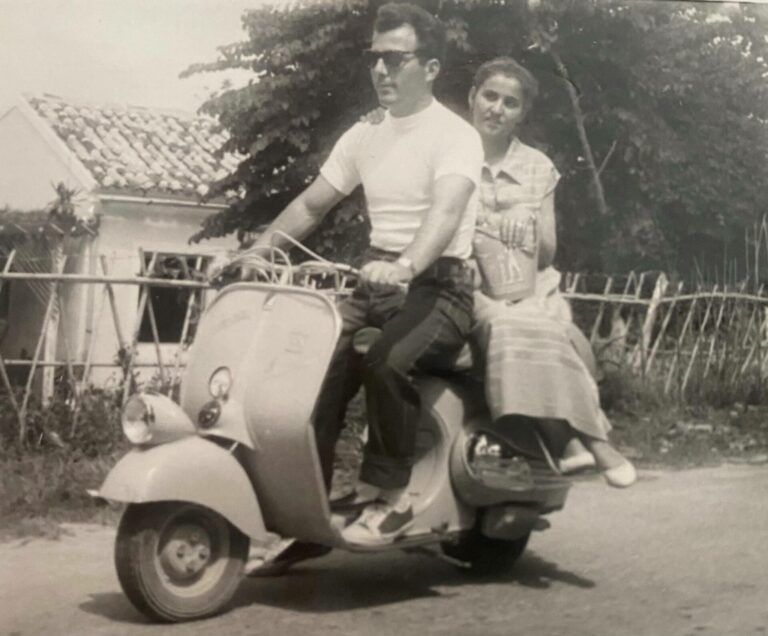

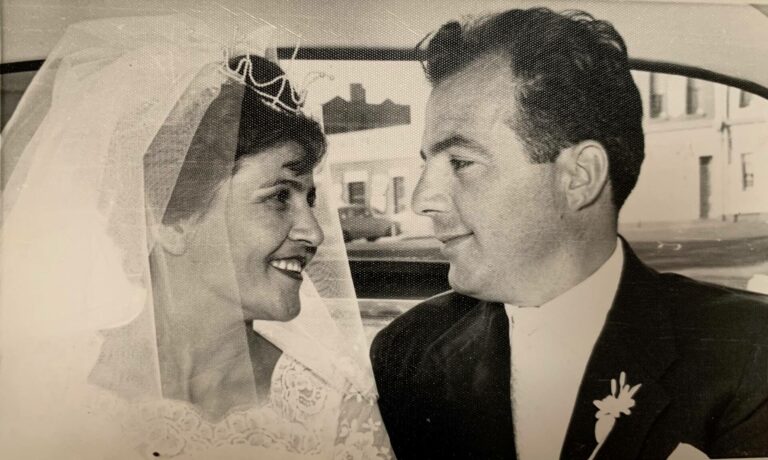

She was completing her nursing studies at the Laiko General Hospital, and all her younger sisters were settled in Athens. She had also met her first love and she longed to be with Corfiot Dionysis Gendis, a leader and P.E. teacher at the Paedopolis of Ziro where her brother George lived. It was for him, she left for Australia in 1961. Her younger sisters, with whom she was very close, also followed her to Australia. Only Maria, the youngest, repatriated after some years.

Ioanna found happiness, and was blessed with children, grandchildren, and a nice home, but to this day there is one regret that still lingers.

Although Ioanna reunited with everyone, including her beloved brother Kostakis whom she hadn’t seen in 25 years, the fact that they never had the opportunity to gather together under the same roof, after that fateful day in 1948, still fills her with sorrow.