Greek authorities have dismantled an alleged criminal organisation involved in human trafficking and illegal adoptions, centred around a surrogacy clinic in Chania, Greece.

The investigation has exposed the exploitation of vulnerable women and the fraudulent practices of the clinic. Approximately 150 Australian families have been affected, unable to access their newborns due to the clinic’s closure amid accusations of human trafficking. The case has led to arrests, shockwaves in the community, and international diplomatic complications.

Greek Organized Crime department officers orchestrated the operation that spanned eight months, ultimately leading to the arrest of eight individuals involved in the organisation. The network had been operating for a decade in multiple regions, including Crete, Thessaloniki, Attica, Agrinio, Ekaterini, and Trikala, AMNA reported.

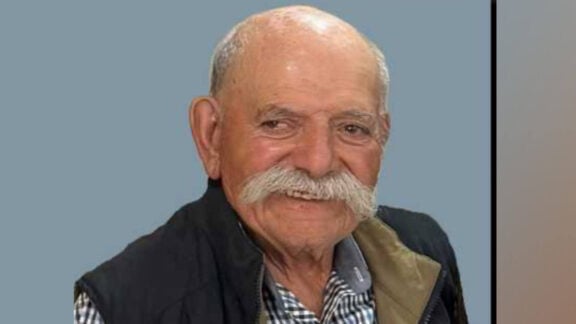

Key figures within the organisation included a 73-year-old gynecologist-obstetrician and clinical director, a 44-year-old scientific director and clinical embryologist PhD, a 44-year-old manager of surrogacy programs, and other individuals with diverse roles such as office workers, midwives, and biologists.

Exploitation and allegations

The heart of the operation was the alleged involvement of the 73-year-old gynaecologist who orchestrated the trafficking scheme. The organisation targeted financially vulnerable women, primarily from countries like Ukraine, Romania, Moldova, Georgia, and Albania. These women were convinced to sell their eggs or act as surrogate mothers. The clinic then paired these women with couples or individuals, including same-sex couples, seeking to have children.

The process involved two stages: first, egg donors underwent special treatments, and in the second stage, the children were handed over to the intended families. Authorities allege that the organisation employed extensive measures to conceal their actions, falsifying medical records, laboratory tests, and certificates to avoid suspicion. The surrogacy programs were priced between €70,000 and €100,000, excluding monthly compensation for surrogate mothers, according to state TV broadcaster ERT and Kathimerini.

Australian families caught up in the scandal

Around 150 Australian families, comprising approximately half of the clinic’s international clientele, have been impacted by the scandal, The Australian and Sky News have reported.

The Mediterranean Fertility Institute, the largest provider of surrogacy in Greece, had been chosen by these families for assisted reproductive procedures. The clinic’s closure has left Australian families heartbroken, unable to hold, see, or access their newborn children due to legal and investigative complexities.

Eight babies – including a number of Australians – are being detained by the Greek government in a high-security section of a Crete hospital, according to The Australian.

Diplomatic efforts and letters from the Australian Ambassador to Greece have been made to facilitate visitation rights and information about hospital care plans for the babies.

“Around half of its clientele are Australian, and this scandal is believed to affect dozens of Australian couples. Just a week ago, it was raided by Greek federal police on accusations of human trafficking and fraud,” Sky News host Sharri Markson said.

“Greek police allege the clinic was a criminal organisation that exploited 169 foreign vulnerable women as egg donors or surrogates and defrauded patients through sham embryo transfers and they’re accused of brokering illegal adoptions. The clinic’s entire medical team have been arrested and imprisoned, accused of child trafficking,” she added.

Due to the clinic’s closure and the ongoing investigations, desperate parents from Australia and Europe, who have come to Crete to collect their newborns, are unable to take their babies home or even hold them.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said that they are “continuing to provide consular assistance and engage actively with Greek authorities in support of a small number of families with surrogacy arrangements in Greece”.

Australia’s Ambassador to Greece, Alison Duncan, personally penned two letters to the Greek government.

“Australian parents need to have visitation rights and access to information about the hospital care plan for their infants” she urged while acknowledging the comprehensive investigation into the Mediterranean Fertility Institute and expressed “hope for a swift resolution to the issue affecting Australian families who unwittingly found themselves caught up in the distressing situation”.

Meanwhile, accounts from affected Australian couples revealed to The Australian a stark contrast between their expectations and the reality they faced.

Upon arrival in Crete, where they anticipated the arrival of their babies, everything appeared ordinary at the fertility institute. The clinic was bustling with doctors, pregnant women, and excited parents awaiting their newborns. However, within days, the clinic was shuttered, and its employees were arrested, leaving parents unable to hold, cuddle, or even see their biological babies.

Instead of celebrating with their newborns, parents were left devastated as the babies were taken away from surrogate mothers and placed under tight security in a neonatal ward at Crete’s Chania Hospital. Desperate letters were dispatched to various authorities, including the hospital and Greek consulate, pleading for compassionate allowances for parents to visit their infants. The hospital, however, was bound by a court order that denied access.

“Parents are now facing the agonizing wait for DNA test results to confirm their biological relationship with their babies. Despite potential positive results, the District Attorney’s office must grant permission for parents to take their children out of the country,” Immigration lawyer Roman Deauna highlighted the challenges related to DNA confirmation and citizenship.

Sam Everingham, Global Director of Growing Families, an organisation that supports families with surrogacy, emphasised the magnitude of the issue.

“About 60 Australian cases enrolled in surrogacy programs per year, 25 Australian surrogacy births per year, another 30 going through donor IVF and another 80 Australian couples with embryos stored there. They would have been doing 300 cases a year. It would be approximately 150 Australians affected who either have embryos there or births on the way,” Everingham said.

“I’ve got women in tears to me on the phone every day saying I just don’t know what to do. It’s been really tough, it’s awful,” said Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand President Dr Luke Rombauts.

“There are a lot of other pending Australian parents who have embryos stuck in the clinic or surrogates who have fled back to Georgia or who are down $30,000 or $60,000 in this,” said Dr Rombauts.

He said there are couples now selling their homes to be able to afford to start over again somewhere else.

The Melbourne IVF connection

Melbourne based Dr Nicholas Lolatgis, Director of the Centre for Infertility Solutions, recommended the Mediterranean Fertility Institute to Australian couples dealing with infertility. Despite the turmoil, he praised Greece’s donor egg program.

Lolatgis penned a letter advocating for parents to have access to their babies during the DNA test wait, highlighting the importance of early bonding.

“That’s why I use them,” he told Sky News.

“The doctors that were involved with the Mediterranean Fertility Institute broke the law in the eyes of the Greek government so they have put a hold on using any embryos created by that clinic. They’re claiming that maybe the fertility institute, when they created the embryos, didn’t use the parents’ sperm and used other sperm… now I think that’s unfounded but nevertheless these are the accusations, so for parents who are there to pick up their babies from the surrogates, they may have to have DNA tests performed.”

In his plea, Lolatgis stressed: “Isolating her [the mother] from her baby is not in the best interest of their baby. It’s not fair,” he said.

Insiders familiar with the matter revealed to AMNA as well as the two Australian news outlets that, in certain cases, investigators have encountered difficulties in associating some newborns with their donor parents due to inadequate record-keeping practices. These insiders conveyed that surrogates were seldom introduced to the intended donor parents, and the documentation was often kept disjointed and occasionally lost.

Allegedly, before the police operation, certain instances might have arisen where donor parents were potentially given children who were not biologically related to them. Additionally, troubling allegations have emerged asserting that surrogate mothers might have contributed their own eggs, subsequently asserting parental rights over the newborn infants.

Neos Kosmos has also reached out to the Greek Embassy in Canberra for a response, however has been told that a statement cannot be provided until Monday, 28 August due to legal reasons.