‘May your brain shrink less than expected for your age.’

This is how Professor George Paxinos signs off his emails and the one wish he offers Neos Kosmos readers at the end of this interview.

His insight comes from a place of knowledge obtained over a 50-year-long study of the human brain.

The Ithaca-born neuroscientist is renowned as the scientist who mapped the brain of humans.

“We’ve made three maps of the entire human brain, each time improving on the previous, and we have made three atlases of the human brain stem. What we’re working on now is an atlas in a novel MRI approach of the entire human brain.”

Paxinos is the Senior Principal Research scientist at Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), part of the University of New South Wales.

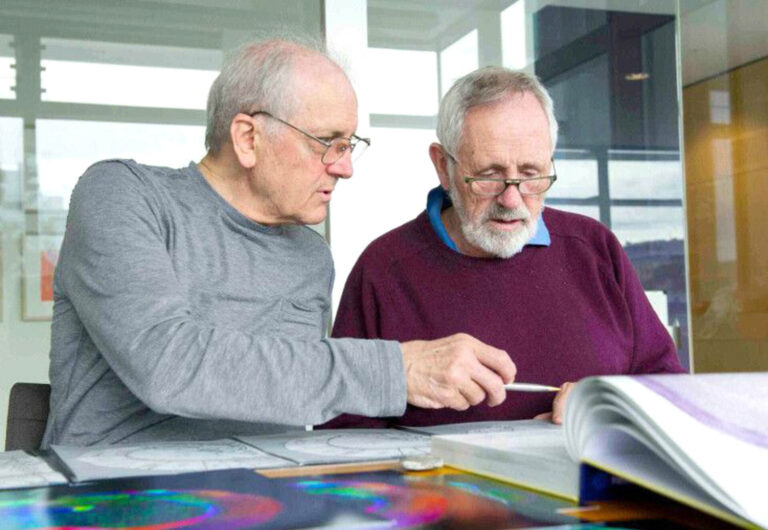

Many of the team’s research breakthroughs he has co-led with long-time collaborator Dr Charles Watson AM (of Curtin University), also leading exponent of brain mapping in the world.

Together, they have identified and named 94 parts of the human brain not previously known.

The “most pleasant” part of the discovery process, he says, is the moment they come across a new brain nucleus and celebrate musically.

“We stop our work and my colleague, Charles Watson, plays the saxophone.

Paxinos alone has published 57 books in brain cartography.

In recent weeks, their research lab published a “technical book of little interest to most”, as he puts it, but of critical importance to all of us, titled ‘MRI/DTI Atlas of the human brainstem’.

“The brainstem is the continuation of the spinal cord and is so important for vital functions like breathing, cardiovascular control, as well as neurotransmitters which are thought to be involved in depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s.

However, novel he spent 21 years writing, is recommended for anyone intrigued by the searing question of our times, whether humans and nature can co-exist in harmony.

With a plot set across four continents, A River Divided follows two identical twins raised apart, who become beacons for the battle to save the environment.

Commenting on the duo of protagonist, Paxinos says:

“In the same fashion that two artists would make two different sculptures out of the same piece of marble, different environments ‘sculpt’ different characters, even when it comes to identical twins.”

The nature VS nurture interplay is one of those universal assumptions proven time and time again to transcend geographical and cultural boundaries.

Nothing uniquely biological in being Greek

Does neuroscience offers insights about what unites people identifying as Hellenes. Are you born Greek, or do you become Greek?

“You become Greek,” he responds, pointing to language and culture as primary denominators in the Greekness equation.

“Take Greek Australians for example. With every generation coming forward, Greekness in things that make it distinguishable is ‘decreasing’. I’ve experienced this with the Greek community in Australia as well as in the US which is an older Greek community.”

“Language is one of the criteria defining Greekness,” he says and recounts the time he offered to donate copies of his novel to a large Greek community club in Australia.

“They told me ‘Thank you very much, but only three of our members can actually read a novel in Greek and they are in residential aged care.'”

According to Paxinos, one of the characteristics associated with Greekness that get little mention is the importance placed on friendship and its practice in meaningful ways.

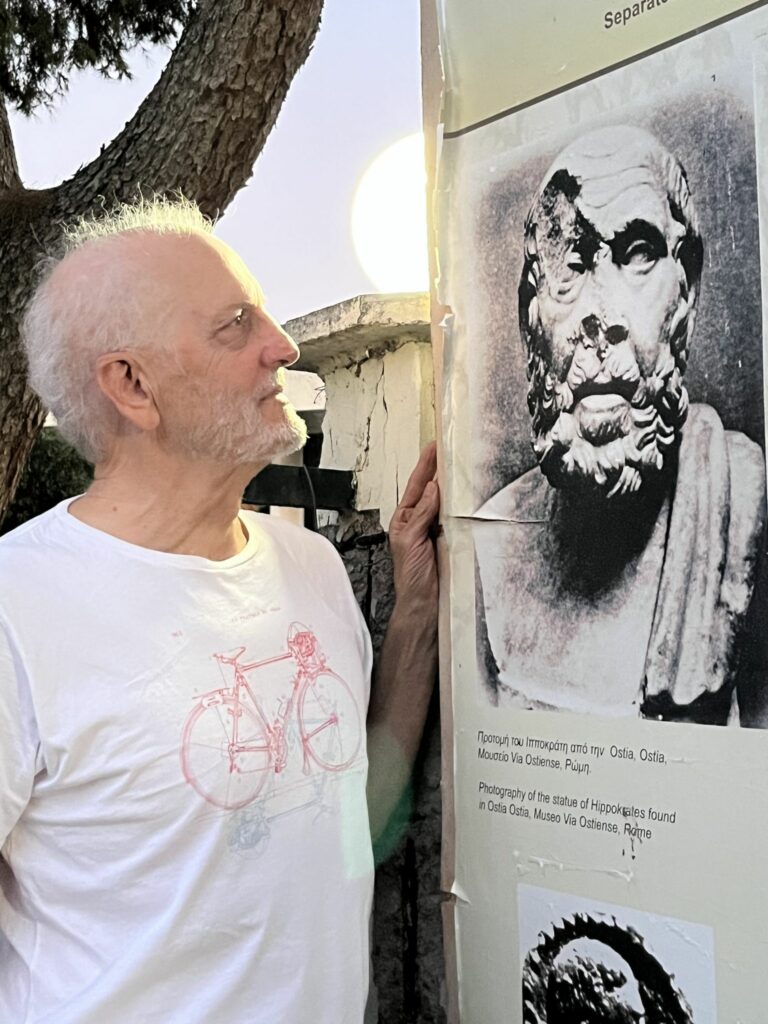

He shares an example from his Greek summer experience when visiting Ithaca, where he co-organises with friends debate sessions in a symposium-like manner.

“We gather for dinner at around 6.30pm. Then, from 7.30pm to 8.30pm we hold the debate, which is followed by live music and singing. All the noise from before, the competition, the arguments, evaporate with singing.”

One of their latest discussion topics, was ‘that considering Homer, Aischylos, Hippocrates and Aristotle, we can conclude that the Greek brain has shrunk during the past 2,500 years.”

“I often get asked ‘how do you explain Greeks’ superiority? Do we have a bigger brain?’. To which I respond ‘For this to be true, you’d have to prove it, and there is no such evidence. In fact, the indications point to the contrary.’

“If you look at Greece’s economy for example, it’s an indication to the contrary for this statement. The same thing with Nobel prizes. Greeks have been awarded two Nobel prizes in literature, but zero in science. Compare this to a similar in population size community worldwide, like the Jewish community, which has claimed over 200 Nobel prizes. Where is Greek superiority?”

The false sense of superiority espoused by some Greeks comes down to “chauvinism” according to Paxinos.

“It’s a different thing to acknowledge the breakthroughs made in architecture, drama, science, politics, at a point in time by Greeks and appreciate this as a Greek person, and a different story to claim you are genetically gifted compared to others.”

Nostalgia a very Greek sickness

Nostalgia for the homeland is something that affects every Greek migrant and Paxinos is no exception.

He visits Ithaca almost every year.

“I have lived in Australia for 50 years now and still miss Ithaca. And when I’m in Ithaca I miss Australia. It’s like my mother. She is not the most beautiful woman on earth but for me she is my mother. In the same way, Ithaca may not be the most beautiful island on earth but it is my birthplace.”

Whether speaking on personal matters or neuroscience, Paxinos’ approach is unassuming.

“I don’t have a switch off button,” he replies when asked when he plans to stop working.

But he does admit that halfway through his 50-year-long trajectory servicing the discipline he loves, he was ready to make the switch to a science he believes is the one most needed today by humanity.

“I had the thought of shifting to environmental studies. That is the cause where I believe the greatest amount of effort is needed today. Because really if you think about it, any cause is dependent on the environment. What I am working on I don’t think will matter in the face of our planet’s destruction, or better say the fact that the planet is becoming less and less friendly for humans.”

Back when he made the career change thought, he had applied for funding in environmental research. But his application was met with a negative response.

“I have been doing what I can but in my personal time through activism and protesting. And I feel I have failed. This is why I wrote a book about the environment, to raise greater awareness about the cause” he says of his novel.

“My science has given me pleasure and though this work I have pursued my passion. But what I think humanity mostly needs today is science servicing the environment.”