There is a distinct photographic narrative of Greek weddings in Melbourne during the post-war mass migratory period of the 1950s and 1960s.

I witnessed these weddings, a little girl enjoying this parallel universe – that co-existed side by side with the other, the more alien one I lived through in a mainstream school in post-war Melbourne. What the wider, let’s call it Anglo-Australian community back then, considered ‘foreign’ or ‘alien’ was a place of knowing for me, a linguistic and cultural safe place.

It was an entrenched working-class reality, with the ubiquitous factories as its collective epicentre, which is why I thought it was so apt that the Democritus League conceived of and curated this collection of black and white photographs within the evocative banner of ‘under the Southern Cross’ a multifarious symbol, an amalgam of safe direction and the imperative and possibilities of workers’ revolt.

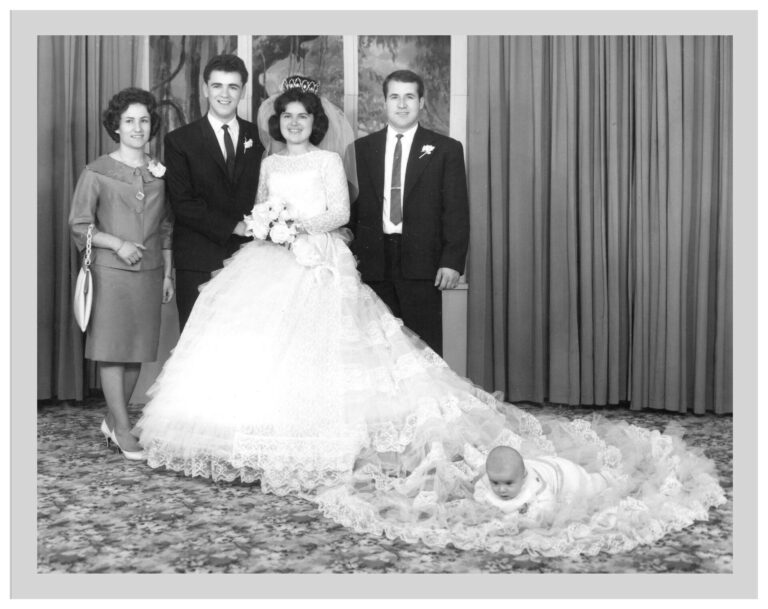

Every photograph in this exhibition is from a private collection. Prized black and white photographs depict a time increasingly looming as long ago. They are all black and white, a reflection of the times. Most – if not all – were taken by one of the few photographers working within the Greek Community at the time.

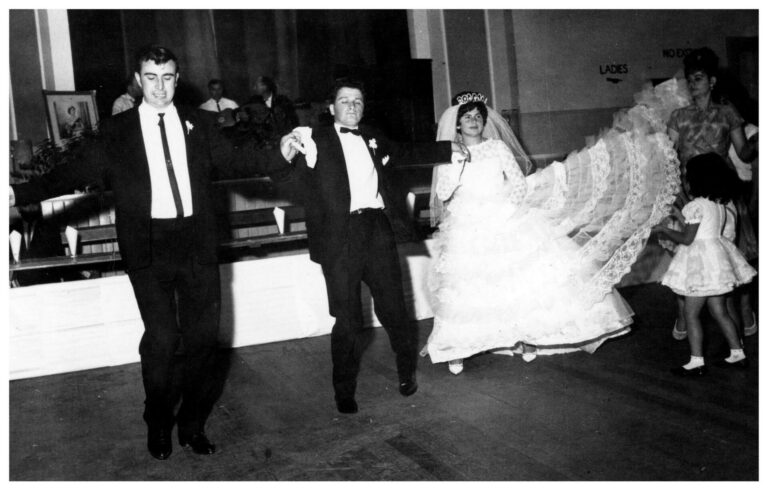

The scenes depicted are either in the church, capturing a moment in the marriage ritual, outside the church where the bride and groom assembled with an assortment of relatives and friends, in the car after the ceremony, at the home or the hall afterwards eating, dancing, and, of course, the very stylised photos in the photographers’ studios.

When I look at these photos, I see beautiful young people. They are physically beautiful young men and women starting a life together. I see gorgeous young women – dressed in spectacular white bridal dresses – with their hair set to perfection on which veils, flowers or tiaras are balanced. They are attended to adoringly by little bridesmaids and flower girls (I served in this position many times and always felt like a movie star) with hair similarly teased to perfection and with very pretty dresses and flowers in their hands.

I see grooms dressed in smart black suits, strikingly handsome young men full of youth and vigour. There is a joyousness in these photographs and such beauty that it must puzzle those outside our community as to why we tear when we see them and why they resonate so deeply when we encounter them.

On one level, there is the sadness that many of these vibrant young people have succumbed to the inevitable passing of time and are now either very elderly, many suffering from a variety of illnesses –some of you, I’m sure, have dealt with parents suffering from dementia and other related illnesses that rob them of their memories. Many of you, like myself, have already lost your precious parents, and with them go their stories – and with them go our stories. Those precious heirlooms are gone for good.

However, this is only part of the story. There is so much more to it than that. We see so much more than what is there when we gaze upon these photographs. Layer upon layer of superimposed images emerge in a cyclic dance; each contextualised within our personal or collective community memory.

These superimposed images alternately come in black and white or in colour; what is certain is that they are textured and nuanced, far from stylised. We see young people escaping the horrors of World War II, the Greek Civil War, and the Junta years from 1967 to 1974. After the Civil War, the rural and urban working classes were starving, decimated physically and emotionally, terrified, and unable to visualise any future in their homeland.

The reality of post-war Greece, coupled with a campaign by an Australian Government desperately seeking people to augment their population – ‘populate or perish’ was the famous catchcry – led hundreds of thousands of Greeks to the other side of the world, tremulously chasing the promise of a better life. This promise harboured a brutal reality that we, their children, were witness to: no English; not only was there no support whatsoever in the factories in which they worked, but they were mercilessly taken advantage of by factory owners, racism was rife on the factory floor and elsewhere in those dark, early post-war days before multiculturalism became officially entrenched, before easy communications, when letters took two months to arrive.

This generation of immigrants was resilient, they survive multiple wars, persecution, and starvation, they were survivors. They knew to hold close what was warm and familiar: the church ritual, their customs, their cooking, the delirium of their bodies moving to their folk dances, and the embrace of their native language, which they clung to for dear life.

They were proud. These photos are a sign of that pride. Even in those dim early days, they wanted to show those back home that their sacrifice in leaving was not in vain. So, the women rented out their fairy tale princess wedding dresses – this is why we see the same gown in numerous photos. They helped each other make lovely clothes to wear as guests at these weddings. The men often rented or lent each other their suits if needed. They all helped with the cooking, making way for guests fitting into houses where several families rented a room.

There is a fascinating photograph where the bride is seen making her way out of the house, her beautiful gown and face glowing against the bleakness of the surrounding factories. It is very doubtful that this photograph would have returned to the family in Greece. What always made their way back home were the studio photographs with the obligatory backdrop of some bucolic representation of lakes and snow-capped mountains through to images of Melbourne with the Yarra River front and centre.

There is yet another lens through which we view these photographs – one inevitably informed by our conceptions of the pervading patriarchal structures at the time. One of our Greek-Australian women writers made a comment in her writings that has always stayed with me. As those of you familiar with my research will know, I see the literature from our immigrant community as a historical text, filling in vital gaps left gapingly open by formal historical texts. In her novel, she expresses incredulity that parents who wouldn’t let their daughters out of the house in Greece because of possible gossip – τι θα πει ο κόσμος – were the same parents who sent their daughters alone to the other side of the world, not knowing what exactly their daughters were going to and what was awaiting them there.

Of course, all know the answer to this. Beyond the poverty and the general desolation of the times, it was the asphyxiating dowry system. The lack of a dowry meant you would have had a negligible chance of marrying in Greece. By contrast, these brave young women who migrated here wanted their right to have a family and, by all accounts, despite – or perhaps because of – the practice of the προξενιό – they managed to do just that.

There is a tendency to focus on the horrors of arranged post-war marriages. In my own research, I explore this facet of it, but this is only one facet. Most of the marriages were, in fact, happy ones. The greatest source of that happiness is their children and grandchildren and the life they managed to carve out for themselves under the most challenging circumstances.

We need to be cautious of our modern-day interpretations when exploring these superimposed shades of meaning. A woman in my extended family who married here in the early 1960s enjoyed a happy marriage. She and her husband loved each other until his passing. Yet, in her official wedding photo, she looks sad. I was a teenager when I asked her about this, and she replied that she was happy with the man arranged for her. She thought him handsome; she could tell he was a kind man and would make a good family man.

Her sadness had to do with the realisation that her wedding day was nothing like the day she had envisaged: in her village, in the local church, with her mother and father, her relatives and friends all around her. Here, she was alone in a foreign country, and at that moment in that photographer’s studio, the reality became unbearable. Once again, our literary writers have given voice to the heartache of this, both from the point of view of the migrant daughters and the mothers’ devastation in Greece on the day of their daughters’ weddings on the other side of the earth.

So, we come back full circle to the photographs – black and white photographs, capturing precious moments, collectively radiating a chapter in our history as a community that is rapidly receding into the mists of time.

Greek Weddings under the Southern Cross November 4 to 12

Steps Gallery, 62 Lygon Street Carlton

Exhibition organised and curated by the Democritus Workers League.

Dr. Konstandina Dounis, a cultural historian at Monash University, who focuses on the impact of immigrant stories in Australian literature, particularly in Greek-Australian women’s writing, challenging canonical forms and enriching historical documentation through her translations from Modern Greek to English.