In the first century of this common era, (CE or AD) Pliny the Elder began his encyclopaedic account of Natural History by noting that there were two ways to madness. One is in the attempt to measure the infinite cosmos, and the other is in the opposite direction, trying to pursue the multiple cosmoi within the world of atoms.

Towards the end of the 18th century, Immanuel Kant, the great German philosopher of the Enlightenment, came to a similar conclusion. Pondering the night stars’ delight and the cosmos’ sublime beauty, he decided that philosophy could neither grasp nor comprehend such big topics.

Probing and unpicking certitudes

Socrates loved to ask questions. He probed and unpicked the certitudes with which others had built the edifice of their arguments. His wife complained that he talked too much and did nothing.

When Timaeus was invited to give his account of the origins and composition of the cosmos, Socrates remained uncharacteristically silent—no clever interjections. There is no hint of flaws in the argument. For once, Socrates said nothing.

Socrates loved to ask questions. He probed and unpicked the certitudes with which others had built the edifice of their arguments. His wife complained that he talked too much and did nothing.

His grumpy refrain has often been interpreted as a protest speculating about things that can never be verified. Socrates wanted to bring philosophy down from the clouds. Socrates wanted to keep his thoughts and feet on the earth.

Ever since Einstein made his breakthroughs, physicists have taken over the role of asking the big questions. The outline of quantum mechanics, the development of string theory, and the discovery of black holes have produced mind-blowing paradigms.

Through this manner of thinking, the boundaries of our thoughts have collapsed, enfolded, and exploded. We no longer see the cosmos as if we were fixed on a stationary point and looking out at it, but as a speck on a little planet moving within it. Everything swirls and blurs.

People are irrational

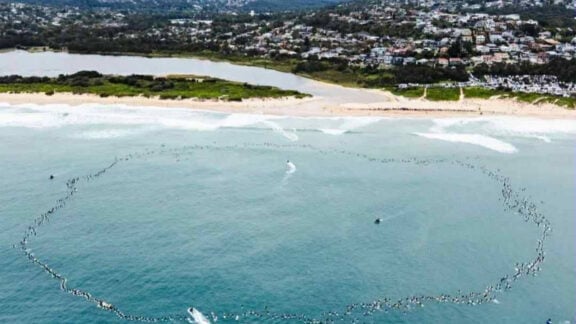

On the last Sunday of every month, I meet a friend and walk along St Kilda beach. One windy day, he told me about an impossible love affair between two married people. They were both lonely in their respective marriages, and they found utter completion in each other.

Her husband had not even looked at her for a decade, but when he discovered their relationship, he made it his mission to destroy her beloved. She returned to his apartment and left the cat he had given her on the driveway.

For an hour, the cat sat alone, staring at the traffic, and then found its way to his entrance. She vanished from his life.

I asked my friend. “Why does a man who no longer cares about his wife hate the fact that she has found love?”

My friend loosened the scarf from around his neck, stared out towards the grey-magenta-blue horizon and shouted. “Because people are irrational!”

Six seagulls screamed back in unison, and Port Phillip Bay shuddered.

One of the torments of psychoanalysis is the claim that we are always thinking. According to Freud, there is no such thing as a slip of the tongue or an innocent joke – they always carry a hidden or secret thought.

Even when you do not think your dreams are working out your deepest thoughts. Under this regime, are we over-thinking things?

Love and hate – a cosmic dance

Making sense of love and hate, the cosmos and atoms is something we feel compelled to achieve. However, there are times when we should pause. Only some things are explicable.

The chaos of the cosmos is beautiful, and the heart is a simple machine with the capacity for infinite madness. Finding space for the horrible in the ordinary order of things is difficult.

Trying to decode contradictory messages can become a descent into infinite regress. Everything can keep unravelling forever. Letting the challenging events stay without explanation is only sometimes a mind failure.

It requires an even deeper hum. There is nothing purely passive about that kind of acceptance.

Pliny made fun of the belief that there should be a God for all our virtues and vices, one for gleaming hard wisdom and another for wine-soaked debauchery.

He also wondered why an all-powerful God lacked the agency to either commit suicide or reverse the flow of time. There was a more straightforward idea in his mind: “God is man helping man”.

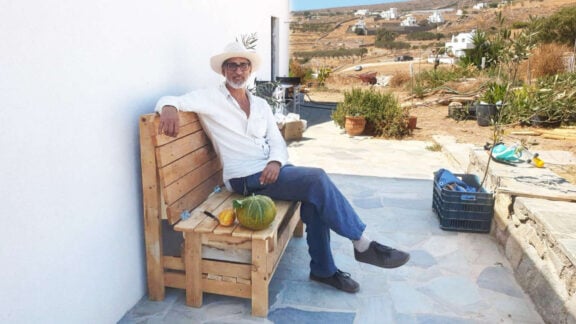

Prof. Nikos Papastergiadis is the Director of the Research Unit in Public Cultures, based at The University of Melbourne. He is a Professor in the School of Culture and Communication at The University of Melbourne.