Every year, politicians come to the Lonsdale Festival and acknowledge the pioneering role of Greek Australians in transforming Australian culture. There would be no Australian multiculturalism without the Jews and the Greeks.

Why are these politicians not shocked when they enter their own flagship institutions? When Juliana Engberg was director of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Culture (ACCA), almost all the international exhibitions she curated included artists from Northwest Europe and the USA. There was no artist from the South.

Her father was Danish, and she took a job as director of the Aarhus festival in Denmark. Imagine if a Vietnamese curator was given the helm of an Australian national institution and confined her program to people of her region? Would she be in the job for over a decade?

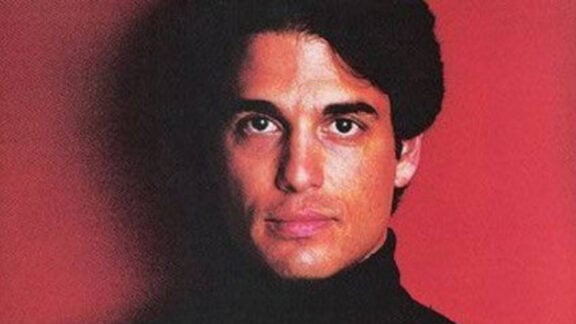

Dean is the son of Serbian migrants and drives a truck for the local council, his almond-shaped eyes and cheekbones outshine Marcello Mastroianni. He was sitting next to me at our daughter’s’ graduation dinner.

He looked up at the stained-glass ceiling designed by Leonard French in the great hall of the National Gallery of Victoria. His mouth stayed open. His eyes remained transfixed.

“You know, when I am in Europe, I visit all the museums, but I have never been in this building before.”

The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) was founded in 1861. Victoria was but a colony in the British Empire, and the birth of Australia was still four decades away. What nation was the gallery representing then?

Last week, the NGV opened Triennial 3 – a global survey of contemporary art. Such a survey aims to provide an overview of emerging trends and themes. What nation does Victoria keep looking towards to find evidence of the modern?

The NGV has 75,000 works in its collection. It will come as no surprise that most artworks are by British-born artists. There are only 17 artworks by artists born in Greece, including six artworks by Janis Kounellis, who spent his entire professional life in Italy, and several Australian artists, like Constanze Zikos, who were born in Greece. A survey of contemporary Greek art would barely fill one wall.

In the forecourt of the NGV is a 7-meter matt black bronze sculpture Really good by David Shrigley.

The sculpture is a black person’s wrist with an elongated phallic thumbs up. It was originally designed to occupy the vacant fourth plinth on Trafalgar Square. It could be seen as a comment on British Imperialism.

The stretching of the black thumb accentuates both a perverse fetish and willful optimism. Shrigley is a comic genius – another great folk artist from the UK. Most of his best work was done in the old days of the telephone.

He kept a notebook and pad by the receiver and would doodle while chatting to friends. However, positioning Really good on St Kilda Road, after all the Yes posters for the referendum have come down, is more than sardonic. What does a black person have to be optimistic about in Australia now?

Triennial 3 comprises works by 100 artists and designers. The installation has been thoughtfully interwoven with significant works from the NGV collection.

Tracy Emin’s narcissistic writhing over the agony of unrequited love sit within a room with sentimental painting from the Victorian era and Wedgewood ceramics.

Some prefer to read Emin through a psychoanalytic lens; I think, like many of the Young British Artists (yBas) of her generation, Emin’s intent was not theoretical. I

n some pop songs, there are genuinely profound moments. The yBas wanted to be as popular as pop stars. Their slogan was: “fuck levity, let’s dance.”

There are many serious works in Triennial 3. It would take the whole weekend to see the exhibition in a fulsome manner. Mun-dirra is a 100-meter-long woven multi-panel mat that hangs in a swirling shell-like formation. It engulfs the viewer, and the fecund smell of grass and ochre transports you to another world.

John Gerrard’s photograph Flare a single pole protruding from a still ocean and emitting whirling gaseous flames, induces an elegiac reverie on planetary precarity. Hoda Afshar’s installation and video with the author Justin Clemens are virtuoso displays of aesthetic intelligence.

Vojtech Kovarik and Heather Swann both reference symbols from Greek antiquity

After the success of Documenta XIV, everyone said that Athens would become the new Berlin. My friends, who are curators and artists, complain that they are overwhelmed by inquiries and struggling with gentrification.

In Triennial 3, Vojtech Kovarik and Heather Swann both reference symbols from Greek antiquity, but once again, there are no artists from Greece.

There is only one Greek name in the catalogue: the Minister for Creative Industries, Steve Dimopoulos, who sends a congratulatory message from the government.

There is only one Greek name in the catalogue: the Minister for Creative Industries, Steve Dimopoulos, who sends a congratulatory message from the government. Museums are never in neat step with community values or mere instruments for soft power in geo-political manoeuvres. Nor should they be! There are too many publics that are competing for attention, and they are not all equal value. For this reason, I applaud the NGV when it adopts a pluralist approach. It now appeals to a much wider audience than it has ever had in its long history.

I am no fan of the ‘Instagrammable’ artworks, but it is no sweat to walk past them. I object to how corporate sponsors colonise public institutions and lament the mixed messages and conflicting demands imposed by government stakeholders.

However, when you look at the national origin for most of the artists in Triennial 3, you cannot help but think: is the NGV’s view of the global contemporary pointing down the barrel of AUKUS.

Meanwhile, at the Islamic Museum in Thornbury, the Greek-Australian artist Philip George has launched an exhibition of photographs and a video called Dunya. It is based on the Arabic word that means a worldly and temporal life: we are here now, but not forever. The photographs reveal the ruins of Hellenistic cities.

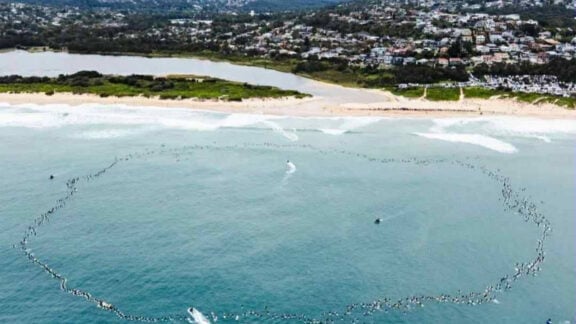

One is from Palmyra, which has now been blown to dust by ISIS, and another is covered by the rising waters of the Mediterranean. In the video, we gain an aerial view of the turquoise waters and little white crests of waves that lap over the grid of the ancient city.

Among the layers in the photographs are fragments of gold leaf and Byzantine iconography. Over the past two decades, George has been composing digital images that echo the layering of history and the futility of empires.

The soundtrack to this video drums the point home with the grievous dirges and ululating amanades sung by Albanian women. Looking back at the year, I find little reason to be cheerful about the prospects of worldly civilisation, and it strikes me that Dunya is the word that should be at the front of St Kilda Road.