The end of a terrible year is around the corner. We need a respite to replenish reserves before 2024 and I am making a concerted effort not to monitor international relations and geopolitics in the Greek and French media to alleviate anxiety.

Venezuela seems to be interested in Guiana’s oil deposits, which might lead to a third military conflict in Latin America, adding to the wars in Eastern Europe and the Middle East that threaten global peace.

As a result, now is the ideal time to write something about cultural misunderstandings between Greeks and French, funny enough to make everyone laugh.

Cinnamon and spice

Let’s talk about spices first. Everyone is a fan of cinnamon scrolls. Cinnamon works like magic and is frequently used in sweet and savoury recipes, especially in Greek food, so almost every Greek home has some cinnamon powder or sticks. This may be why my family brought me cinnamon when they visited me in France.

Even though I was attempting in vain to explain that I could find cinnamon in almost any supermarket nearby.

As usual, the tsunami of cinnamon persisted.

This is because, as we already know, a Greek family still views a man who is forty or fifty years old as a child who needs to be constantly looked after. I finally had to give up one of my secrets to stop receiving cinnamon jars. I love Indian grocery stores in Paris, primarily owned by residents of Pondicherry.

This territory was a French colony for 280 years, up until 1956. Spices of every kind can be found in these shops. That being said, it took some time before the cinnamon shipments ended. After all, there are many ways to express love, and in my situation, cinnamon was one of them.

Chicken wars

Now it is time to write about chicken. Practically everyone likes chicken. Children love chicken nuggets, and roasting chicken in the oven with potatoes drenched in lemon juice is a well-known Greek dish.

However, a month ago in Paris, chickens put me in a risky situation, or the price of the chicken, to be more precise.

I understand rising food prices and inflation are hotly debated nowadays. Everybody in Europe complains about inflation whether they live in Greece or France.

Nevertheless, prices vary significantly among nations for the same goods.

Nobody believed me when I told my French colleagues how much fresh chicken meat cost per kilogram in Greece last summer.

I was instantly written off as a liar. The French reaction was adverse even before I showed them the smartphone photo I had taken from a Greek supermarket. The price of the Greek chicken was considered too good to be true.

There were accusations of having used a photo editing program or AI. I had to deal with some upset audiences.

I was proven right a few days later by one of my French colleagues, whose daughter confirmed that what I was saying was accurate after spending a week in Athens.

What transpired caused me to reflect deeply on the profound shift in how people view the world. Nowadays, we undoubtedly obtain a vast amount of data and information because of modern technology.

Hard to know the truth

Unfortunately, people are less willing to believe what they learn immediately due to the widespread use of AI-generated deep fakes and a flood of fake news.

To ensure everything is fine, they frequently need to double-check independently.

From this perspective, the reaction to what I had said to my French colleagues was not entirely unexpected. However, fact-checking can now be completed more quickly than in the past, which is positive.

Because so many things are taken for granted, clichés and prejudices are still powerful, and individuals aren’t always willing to step out of their comfort zone.

Therefore, please think positively and with curiosity and openness as much as possible.

And let’s hope for a better future for all of us next year.

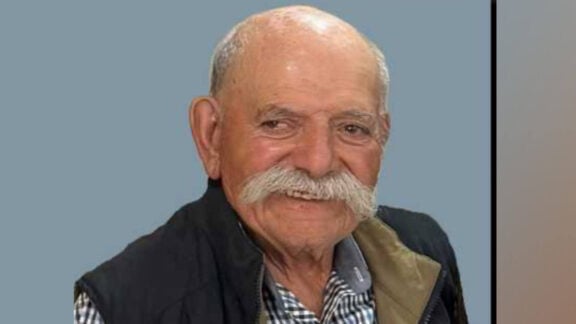

Dr George Tassiopoulos is a Greek French political scientist, with a doctorate in political science from the University of East Paris. He was born in Athens, and has lived in France for the past 22 years where he teaches geopolitics in a business school in Paris.