David Beckham’s most endearing feature is his profound gratitude. In the recent Netflix documentary Beckham (2023), we see his gratitude towards his father, Ted’s dedication, his wife Victoria Adams’s forbearance, and his manager Sir Alex Ferguson’s guidance.

He shows more than a feeling of gratitude because of the individual support he has received. We also have a feeling of gratefulness for all the people he loves. It spreads.

I had the good fortune to begin my academic career at Manchester University while Manchester United recruited Eric Cantona from over the Pennines. The stolid coach at Leeds had no idea how to use mad Eric.

Sir Alex saw a reflection of himself in the wild stallion. Eric’s roommate in the French national team was the brother of one of my students. We accidentally met at the Atlas Bar and spent the afternoon discussing political economy and uneven development in the Third World.

I told him that one of my colleagues invented the phrase Third World. His eyes lit up. Erik never turned the conversation onto soccer or back on himself.The younger players were in awe of his dress style and self-assuredness, but his erudition confounded them. Eric would read the poems of Rimbaud before a match; they chanted Rambo. In the 1990s, the most prominent pundit on the BBC’s Match of the Day was a gruff Scott called Alan Hansen. At the start of the season, he looked at the Manchester United list, which included Beckham, Scholes, Butt, and the Neville brothers.

You can’t win anything with kids!

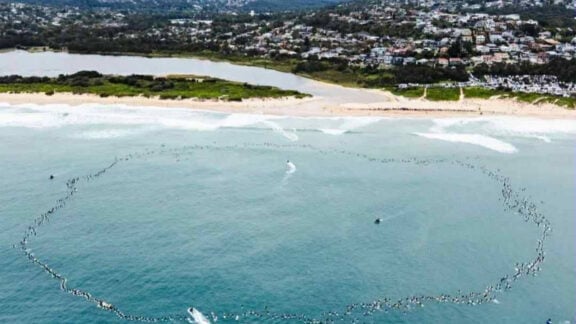

He yelled out the only comment that he would come to regret. “You can’t win anything with kids.” They went on to win everything! Ole Gunner Solskjaer, the super substitute who scored the goal in extra time for the European Cup, was married to a gifted artist called Silje. She attended one of my classes, and when she cited my work, I half-jokingly said she should offer me a ticket to a match. She had zero interest in soccer and gladly handed over a pair of season tickets in the ‘wives and girlfriends’ (WAGS) section.

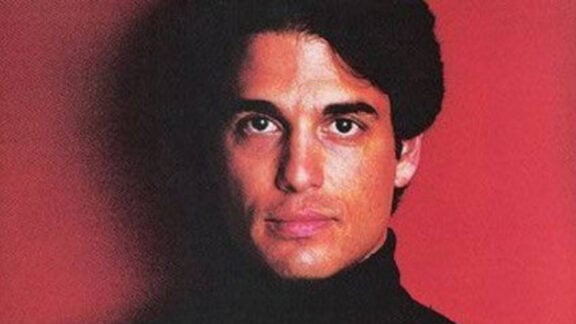

Even my Liverpool mates were keen to be seated there. Beckham revealed that the place he felt most safe was the soccer pitch. I saw him in a queue to clear customs at Manchester Airport. Some of the older guys in the team were mocking his haircut and messing with his Hermes bags. As a young man, he had a gorgeous androgynous face. Harry Styles, who has the name that is more suited to a mechanic in Huddersfield, has a similar effect on women of all ages.

The attention on Beckham was both a source of pleasure and discomfort. At the airport, the immigration officer froze. Her mouth was lower than the desk, and the hand holding the stamp was not moving. Steve Bruce was still ruffling Beckham’s hair, and his body visibly squirmed, but he kept smiling and pleading: ‘C’mon on guys’. In the documentary, we see Beckham folding socks, checking lights, arranging the condiments, wiping surfaces, and choosing his clothes a week in advance. His need for structure and pursuit of goals belies vulnerability and nervousness with the world.

On the soccer field, he knew the boundaries. He could work the ball to defy geometry. He could chip over defensive walls with nonchalant grace. He would leave goalkeepers standing either on the wrong side of the net or seemingly weighted down by a lead-filled gravity. He was tall but not imposing. The French say, ‘There are two types of players, one that carries the piano, and the other that plays.’ Eric could do both.

The Oedipal struggle

Beckham was no U-Haul guy, and it was a mistake to burden him with being Captain of England. His ego craved that role, but he was most free on the wing when the Great Dane Schmeichel, Keane the enforcer and Eric the King were the team’s spine.

Who knows how the Oedipal struggle played out in his fallout with Sir Alex? It started in the dressing room at half-time. The team was playing poorly. Sir Alex came storming in. There was a loose boot on the floor. Sir Alex kicked it, and it went flying across the room. It nicked Beckham just above the eye. He dropped his head in the soccer man’s agony. Sir Alex probably thought: ‘What is your problem, son? You should have ducked; in any case, you deserved it!’ The subsequent media frenzy over the cut to the eyebrow, which Beckham partly fuelled, was a betrayal of the dressing room code.

Sir Alex loved David like a son. But he never forgave him. Beckham neither blamed Sir Alex nor felt guilty. To this day, his gratitude seems genuine. Sir Alex turned the talented lad that Ted had drilled into a star.

There was no prouder smile than Sir Alex’s when he posed with Beckham on the morning of his first senior game. In the same photo, Beckham is leaning into Sir Alex’s outstretched arm and shoulder. There is a halo of love that lifts both above the ground. So, what is gratitude? It is more than an expression of thanks and appreciation.

Distinguishing between gratitude and debt repayments

Seneca, the Roman statesman and Stoic philosopher, distinguished between gratitude and debt repayments. Some transactions need reciprocation to clear the table. However, there are other gifts whose true weight is invisible.

How do you acknowledge this kind of benefit that is received from others? Perhaps gratitude is also a willingness to open yourself – an act of finding the strength to become something that you might not have achieved if not for the influence of that other person. It is also a moment of pause, taking time to recognise the limits that previously constrained you and savour the horizon of possibility before you.

It is hard to admit it, but it is in the dark trauma of breaking up that you also see the most light.

Sir Alex cut Beckham off. It was brutal. It made Beckham feel homeless.

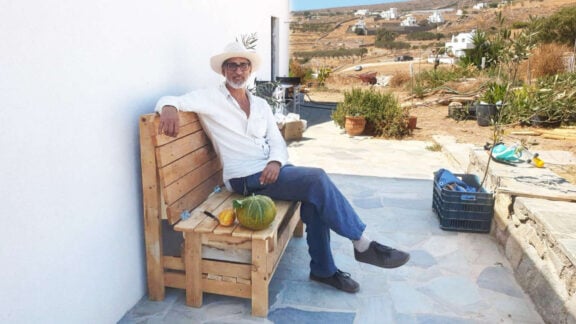

Prof. Nikos Papastergiadis is the Director of the Research Unit in Public Cultures, based at The University of Melbourne. He is a Professor in the School of Culture and Communication at The University of Melbourne.