Maria Christodoulou, experienced the terror of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in the summer of 1974. Her story, is filled with sorrow and paints a vivid picture of destruction and human suffering. Despite the 50 years that have passed since then, images are alive in her mind, unfolding today in a torrent of expressive language that captivates and enchants with the Cypriot dialect characteristic of her speech.

Born in Morphou, an area of Cyprus now occupied, Maria recalls the past with both nostalgia and pain.

“I was born in Morphou, a very fertile place, full of fragrant orange groves, especially when the trees were in bloom. You would think you were entering paradise, such was the beautiful smell. It was an earthly paradise,” Christodoulou says.

Her family – her father, mother, brother, sister, and herself led a happy life in Morphou – there was peace.

“I finished high school, got married and we lived in Morphou for eight years.”

Their happiness was violently interrupted on the morning of the invasion.

“I was about to give birth to my second child. I was expecting when the war began. One morning, we heard that the Turks had entered Kyrenia. From Morphou, we saw a dense cloud of smoke rising from Kyrenia.

“You couldn’t distinguish the sky from the ground. Everything was black, pitch black.”

The residents of Morphou at first didn’t believe the invasion was real.

“They started yelling ‘The Turks were coming’, but we didn’t believe it,” Maria recalls. The reality was harsh.

“People from Kyrenia began fleeing south, ending up in Morphou. They sought refuge, and we opened our homes to them.”

Maria describes the situation and emotions brim to the top.

“We laid blankets on the floor, opened our closets, gave clothes to the people, and shared food. We had both familiar and unfamiliar faces among us. We offered whatever we could and stayed together.”

“It was very difficult for those who were left homeless, because I experienced the same with the second invasion.”

MY SON, WHERE ARE YOU GOING?

“When it happened (the invasion), I was ready to give birth and I was terrified,” Christodoulou recalls.

“I would look at the stars at night and think they were planes about to start bombing us because we were under blackout.

“We were not allowed to turn on lights. To enter the house, we would light a small candle just to see how to move around because it was very dangerous—when they saw light, they would drop bombs.”

The situation was more difficult because of her 22 months old son.

“He understood that something was happening and all he wanted was his uncle, my brother, who was a soldier.

“When he came and found us after the first round, he saw him and got scared because he was all bearded, unshaven, and dirty, covered in dirt.”

Her brother, like many other enlisted men , could not share the details.

“It wasn’t allowed. He came, changed his clothes, and put on his uniform. Then my mother knelt in the yard and said to him, ‘My son, where are you going? Where are you going?’ And he had to go to his duty, they all had to go.”

Maria Christodoulou remembers the anxiety of those days. “He came back, but the anxiety was immense.”

THE EMEMY APPROACHES

Three weeks had passed since July 20 after the Turks advanced toward Morphou. They reached Kapouti, “a picturesque village where locals used to go for summer strolls and buy traditional dishes like oven-baked kleftiko to enjoy with their families,” Christodoulou says.

This memory might seem out of place in our conversation, but it isn’t. Christodoulou’s desire to counter every bad moment she describes with a sweet memory of something beautiful is evident. The memories make the situation even more painful.

The residents of Kapouti, the Kapouthiotes, descended towards Morphou, loaded with fear. The prospect of Morphou’s occupation by the Turks was very likely – panic began to spread. Rumors and anxieties multiplied as the roads connecting Morphou to Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, were now closed. The fear of being cut off and isolated grew.

Christodoulou was about to give birth. If labour pains struck during the journey to Nicosia, the obstacles would be insurmountable. The main roads were closed, and the route to nearby Mitsero, which usually took 45 minutes, now nede three hours due to detours and blackout conditions.

“When they started saying the Turks would arrive, and people began gathering their personal things, I told my husband, ‘Do you think I should put my jewelry in a box in case I go into labour so my mom and sister can bring it?’ And that’s how I saved my jewelry, nothing else.”

CHILDBIRTH UNDER BOMBARDMENT

Around midnight on August 12, rumours began circulating that the Turks occupying Morphou.

Maria Christodoulou can’t forget that day, the reality of war marked the most profound event of her life – birth.

“They were shouting, ‘The Turks are coming!’ when I went into labour. My husband took me to a private clinic in Nicosia – the same one where I gave birth to my son – because we were family friends with the doctor and his wife.”

Fortunately , the doctor was already at the clinic for another delivery, “of a young Greek woman whose husband was in the Hellenic Force of Cyprus (ELDYK) and was at war while she was giving birth in the clinic.”

“When I arrived, the doctor said, ‘Hurry up,’ because the baby was ready to come after three hours in the car.”

The doctor couldn’t turn the lights on in fear that Turkish planes would bomb the area. He lit candles and, with the help of the nurse, delivered the baby. They placed Christodoulou in a room as the other young woman who gave birth. Both cried – Maria had a baby girl, and the other a boy. The doctor trying to comfort them joked, “You gave birth together; now you should marry them.”

“All I could think about was my other baby, my husband, my mom, my dad, my sister. I wanted to leave as soon as possible to go and find them,” says Maria, who felt uncertainty and insecurity being away from her loved ones under such dire circumstances.

THE FAMILY FLEES TO MITSERO

After Christodoulou and her family fled to Mitsero, where they had acquaintances.

“We had a friendship with a couple of teachers from the primary school in Mitsero. Kostas, who was also the school principal, and his wife suggested we go there if things got difficult.

“Just before we left Morphou, they said, ‘Here, we are safe from the Turks.’

“My husband took everyone in their cars. I remember my father had just bought a pickup truck for our orchards, and he loaded them all in the back.

The couple of friends had a small apartment next to the one provided by the school for themas teachers. The apartment housed the school’s gym equipment, books, and other things. It had one bedroom, a small kitchen, a hallway, and a storage room. That’s where all my relatives went—12 people in total.

There was the issue of supplies which Maria Christodoulou’s father resolved.

“There wasn’t milk for the babies, my father took his car and drove around the surrounding areas to buy whatever he could find: meat, fish, legumes, whole cartons of milk.

“He bought food for all the children – the village was now filled with refugees, he would give what he brought to everyone and kept a few things for us,” Maria explains.

MARIA REUNITES WITH HER FAMILY

A day after she gave birth, August 14, the second phase of the Turkish invasion began, with the Turks entering Morphou, bringing terror and destruction.

“The day after I gave birth to my daughter, August 14, the second invasion began. No one could come to the clinic because the roads were closed due to the bombings. My father and my husband spent the entire night transporting people to Mitsero.

“Around 4am on August 15, my father came to the clinic. He banged on the door loudly, and we were scared it was the Turks. When he told the doctor who he was, they let him in, and he said he wanted to take me. The doctor warned him that it wasn’t wise due to the risk of hemorrhaging.

‘I will take my child with me,’ my father said.

‘If anything happens, I will bring her back.’

He took the bag that had only my maternity clothes and a pregnancy dress. I put on the dress, holding my baby in my arms, got into my father’s car, and we escaped.

Above war planes flew, and I was prayed. I cried and cried and cried,” says Maria Christodoulou, and her eyes well with tears .

“We arrived in Mitsero. My son saw me and was overjoyed. ‘Mom, mom, my mom,’ he cried.

“I thought, ‘We’ve become true refugees,'” says Christodoulou.

FATHER SAVED BY A MIRACLE…

“When we arrived in Mitsero and my father dropped me off at the house, and said, he’d go to Morphou to open the cupboards, pack the sheets, blankets, and our clothes, and bring everything here.’

“– ‘Dad, don’t go; the Turks will catch you.’ I cried”

“– ‘No, I will go to feed the chickens too’ he was adamant”

Despite us pleading with him, he didn’t listen. He drove off.

“At the entrance of Morphou, men with shaved heads and ponytails stopped him and pointed their guns at him. They had a Greek policeman with them. They asked him to follow them to the police station where they had planned to execute him.

“Although my father did not understand , he sensed the danger from their actions and the policeman’s warning to be careful. The men started walking and my father followed as they ordered.

“He let them get a bit ahead and then turned down a side street they didn’t know and hit the gas as hard as he could. They started shooting at him, but he managed to escape through routes they didn’t know.”

THEN THE MIRACLE…

Maria continues says that her father, who was “saved by a miracle, became a miracle for others”.

“On the road my father randomly chose to escape, he found three soldiers from our village who had gotten lost and didn’t know how to return. He helped them hide in his car and brought them to Mitsero.

“Those boys were lucky, and so was my father, who wasn’t killed. I remember when he returned to Mitsero, he was as white as a wall from fear and anxiety. One of those soldiers is here in Melbourne. Whenever he saw my father, he would say, ‘Uncle, you saved my life'”, Christodoulou says.

MORPHOU: “THE PROMISED LAND”

Christodoulou never returned to Morphou, though she did visit relatives in Limassol in 1995. Her heart remains there. It is anchored in memories of the place that nurtured her and that she loved so much.

“In Morphou, where we lived, it was like the Promised Land. It was a rich area. There were orange groves, and the people were prosperous. It had schools, and students from all the surrounding areas would come by bus to attend one of the high schools there.

“Unfortunately, my siblings who visited recently told me that now everything is in ruins.”

THE FAMILY HOME

The family home in Morphou has undergone changes since they left. It houses Turkish Cypriots from Paphos. Christodoulou’s son visited the family home and had emotional moments with the new occupants.

“My son went twice with his family to our house. The first time he went, he told me that the people living there realised who he was from the photos that had remained in the house.”

“The mayor of Morphou was living in my house, and he told him that he had kept some of my and my husband’s belongings in the attic.”

The new occupants, had also found a room filled with children’s toys, which were her son’s toys from when he was little.

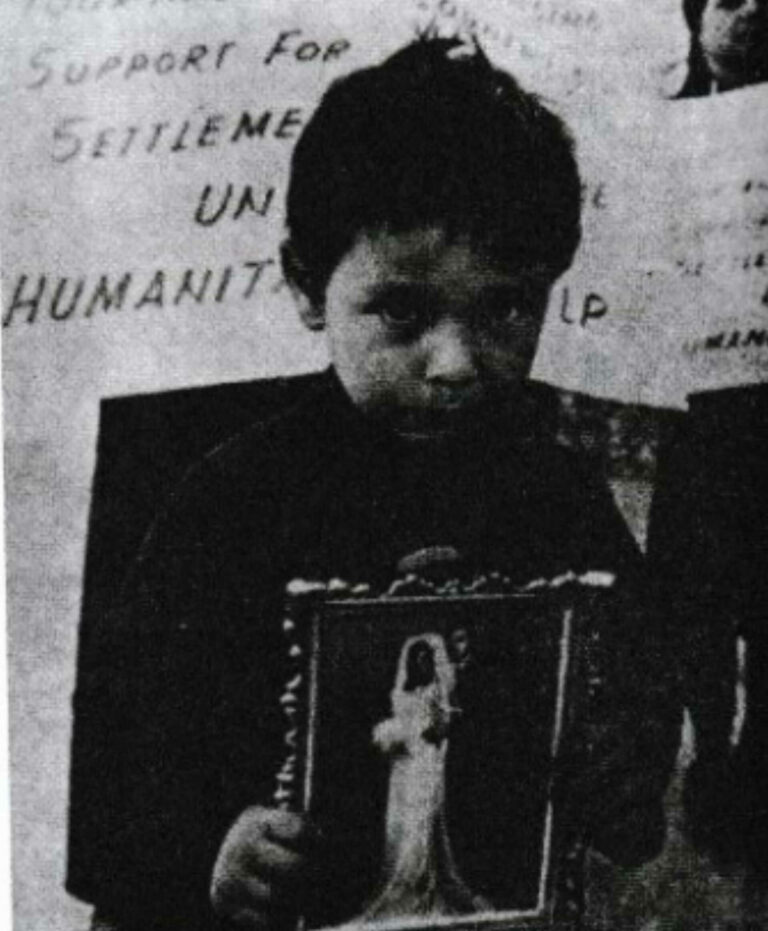

Before he left, they gave him an old, empty album with a cover depicting Cyprus and had placed a sprig of jasmine from Maria’s garden and two of her wedding photos inside.

The photos reached Maria, but they were never hung on the wall of her home in Melbourne. The reason was the pain they caused her daughter.

“My daughter, when she saw the photos, wouldn’t stop crying, so I took them and put them high up in the closet so she wouldn’t see them and get upset. Sometimes, my sister and I take them down, look at them, and then put them back up there,” says Maria.

“AND YOU ARE PEOPLE, AND I AM PEOPLE”

Maria Christodoulou grieves for what was left behind, and a life that was cut in half. She grieves for the Turks in Cyprus who, before the invasion, were her own and with whom they lived together harmoniously and lovingly, and suddenly had to become enemies.

“We coexisted with the Turkish Cypriots it was natural. We had no differences; we were united. Turkish people would come and go from our house because they were very good people who appreciated and helped us, just as we did them.

I remember with love Uncle Arif, Aunt Irene, and their children, Tilper, Zifer, Ahmet, and Halil, who now live in Sydney. Uncle Arif used to come from his village, Elia, and bring us cheese and greens,” Maria says and continues:

“At my wedding, about a third of the guests were Turkish. They came loaded with lambs and chickens for our celebration. These moments remain alive in me, and I never forget them.”

When asked if her feelings changed after the invasion, her answer is brief and categorical.

“My feelings have not changed for these people, even now,I will invite them to my home. The Turks were a minority in Cyprus and tried to learn Greek to communicate with us, and we accepted them as if they were our own. They were good people, as if they were Greek,” she says.

WILL IT BE AGAIN IN YEARS TO COME?

Maria Christodoulou knows that as much as she wants to, she will only live in her home again in her dreams.

She tells me jokingly, “I make plans in my mind and wonder, will we take Morphou back again with the passing of time – like we say about Constantinople? I don’t think so. If they give it back to us, we will build a summer house to go there for holidays.”

– Does this story hurt you, Maria?

– It hurts me a lot. I love Cyprus; it is a very beautiful island…