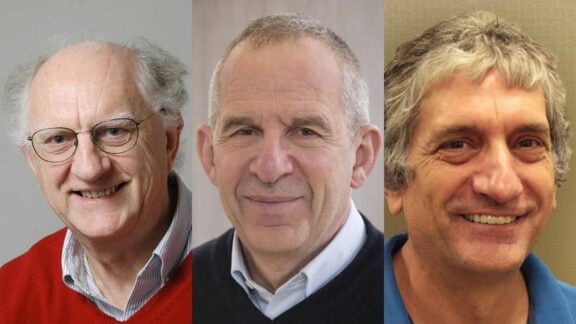

On the living room table Vangelis Alexiou has laid out the black-and-white photographs of his youth. Among them is a unique snapshot of his parents, taken by him when he was still a teenager, a few years before he set out for Australia.

In the blurry picture, his parents, Nikolaos and Angeliki, stand proudly, but their faces reveal the pain and hardship they endured.

We often document in Neos Kosmos, the experiences of Greeks who emigrated to Australia – the nostalgia for their homeland, the obstacles they overcame to build a better life for themselves and their children. Yet we rarely hear about the lives of the parents they left behind.

These parents, who spent the prime of their lives in the darkness of war, Nazi occupation followed by the Greek Civil War – watched as their children left one-by-one, to seek their fortune overseas. To Australia, a land so distant, most of them did not believe they would ever meet again.

People used to grow up, live and died in the same place – the intergenerational connection was strong and constant for centuries, so migration seemed like a final goodbye. It wasn’t just that they saw their children leave; it was that with their departure, their world as they knew it was changed forever.

Longing for a return

Nikolaos Alexiou, born in 1910 in Paliochori, Fthiotida, lived with the hope that his only son -and one of his four children who emigrated- would someday return. This was, after all, what his son had promised him, and the reason why Vangelis Alexiou refrained from buying a house in Melbourne while his father was still alive. He didn’t want to take away the hope that gave him comfort.

From a very young age, Vangelis was his father’s support—the first child and son during very difficult years. It was to him the doctor would say, when he was only 5 or 6 years old, to pass on to his father, the sad message that his little brother was very sick and would die.

When the partisans came and gathered all the men of the village of Krikello in Evrytania—his mother’s village where they lived—among them was his father, who had to abandon his family and flee to the mountains in 1947.

Shortly afterward, when the order came to evacuate the villages of Evrytania, Vangelis, only eight, was forced to grow up quickly to help his mother and sisters survive in Galatas, where they fled.

“The most destructive war is the civil war because people know each other. They know each other’s roots,” Vangelis says, as he recounts his father’s life.

“He was a gentle man. His life was hard, tragic, full of conflict. He alone knows what he went through,” he says, describing how his father was captured and taken to prison in Lamia, from where his siblings helped acquit him, allowing him to reunite with his family after almost three years.

They returned back to their family home in Krikello, a deserted village, in 1950, when the civil war had ended and people began rebuilding their lives from scratch. Vangelis was 15 years old when he decided to leave for Volos to learn the trade of a tailor, but he also wanted to finish high school.

“I was determined to finish high school,” he says, explaining that it was also his father’s dream to see him study and find his place in society, honouring the family name. But, he also had five sisters to take care of.

And so, instead of joining the Army, he was given the opportunity to join the military police.

“I joined the Gendarmerie because I had obligations, I had five sisters who needed to get married. During those times, for a girl to get married you had to pay, as if it was a business deal.”

During his posting in Thessaloniki, Vangelis went to work, simultaneously attending night school whilst also working in a tailor shop to meet the growing financial demands. There, he would meet and fall in love with his future wife, Eleni, who was just 17 at the time.

When he settled the dowry for the first sister that got married – a house in Thessaloniki – he had to find another way to pay the bills. Emigration to Australia presented itself as the only solution.

“I signed off a loan so things got tight. I couldn’t stay in Greece any longer.”

“But my father was full of sorrow. ‘Why are you leaving?’ he would say to me…”

Vangelis did the paperwork for his migration secretly, from Paleochori, so as not to upset his father.

When the time for his departure finally came, he went to see him, and to comfort him, he took Eleni along, the woman he was pledged to marry. “I took her to the village and told him ‘Father, this is your daughter-in-law.’ And then I left.”

The last time he saw his father

It was 1964. This was the last time he saw his father alive. A telegram from Fthiotida in August 1971 informed him of his father’s sudden passing at the age of 61. He was found dead from a head injury in a field just a few meters from his home.

Vangelis doesn’t believe the official version, that his father’s death was an accident, and shows me an article published in Neos Kosmos referring to Dimitris Verioni’s book, Deaths During the Junta. In it, the author presents 247 named cases of deaths for which the regime and its circles were responsible or blamed.

“I didn’t get enough of him, I didn’t experience him much as a father, because I was always far from him,” he says.

The article he read seems to have awakened in him the pain of his father’s untimely -and to him- suspicious death.

He had left for Greece immediately on hearing the tragic news, and made some attempts to investigate the circumstances of his death, but the cost of a private investigation was a small fortune -specifically 25,000 drachmas. A huge sum in those times. And besides, the lawyer discouraged him from going ahead.

History and photos – a narrative of life

“They say, ‘History judges fairly, but it takes time’. That is why I wanted, if I could, to offer something to my father, to do him justice.”

It would take Vangelis another 50 years to return to Greece.

As we sit in his home in Albert Park— 53 years since from father’s death—we look at the photos hanging around the living room. The images tell stories of the beautiful family he created thousands of miles away from the place he was born. Vangelis Alexiou’s life, the hard work in the tailor shop he maintained on Mills Street for decades, would surely have made his father smile, knowing his son had made it.

On the occasion of Father’s Day, the life of Nikolaos Alexiou serves as tribute to him and all those fathers who sacrificed their best years in war and conflict, who didn’t get a chance to raise their children, enjoy fatherhood, or meet their grandchildren born far away.