How do you nurture happiness at home during the often turbulent adolescent years? How can parents and carers avoid the pitfalls that fracture relationships with teenagers? More importantly, how can we help young people build resilience, independence, and a sense of connection amid the rush for new experiences?

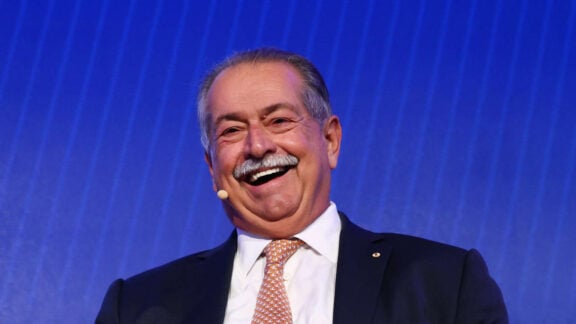

Melbourne clinical psychologist Dr Jari Evertsz, with roots in Greece, hears these questions often. With over 20 years in clinical and policy settings in Australia and overseas, as well as in juvenile justice and high-security prisons, she’s seen both the struggles and the turning points. As the director of Grow Psychology she is recognised for her expertise in addressing difficult behaviours in children and teens.

Dr. Evertsz’s book, The Well-Behaved Teenager (and other myths), is a type of guide for parents and carers, who might feel overwhelmed, and disconnected. The psychologist also writes for those who may be unsure of how to navigate this ever-changing and oft demanding phase of life.

“Seeing and hearing the same things being said, many weeks of the year, week in and week out… people describing very similar situations and feeling very stressed, got me thinking that if it’s happening so often, let’s try and put the experience that I’ve had down on paper. They don’t necessarily need to go and see a counsellor to give some new ideas a try,” Dr. Evertsz says.

Using examples of common everyday teenage behaviours and outlining the science behind them, Dr. Evertsz shows how a few practical adjustments can improve the family environment and strengthen relationships at home.

This phase can be more rewarding than most think

Dr Evertsz wants one message to resonate, that raising teenagers doesn’t have to be that tough.

“Worrying less about being the parent of a teenager, means you can really enjoy it,” she says. “Once you think that things are going to turn out okay, and you’ve got some strategies to hand, it’s a lovely phase.”

Dr Evertsz urges parents to consider what’s happening inside their child’s brain and try to understand.

“People often think that if teenagers exhibit difficult behaviours, it means that they have underlying poor values, or that they will not turn out to be good people.That’s not true.

Dr Evertsz doesn’t want to focus on the “the hormones issue” and says “we’re all aware of that”.

She points to two things that influence how teenagers process situations, “the inhibitory mechanisms in the brain” and “rigidity” on how teens process situations.

“The inhibitory mechanism— acts like police officers issuing us with cautions and safety warnings” and Dr Evertsz says “it is not keeping pace with the very fast growth of the teenage brain in other areas, such as finding new experiences, thrill seeking, wanting to make new social connections.”

The second, factor, “rigidity”, regardless of teens’ “processing speed” can inhibit rational responses.

“If you’ve ever tried to have a sensible argument with a teenager, you might find that they just keep coming back to the same point of view. They’ve got this cognitive rigidity still in mid-teens which develops later.”

Teens’ capacity for flexibility is still under construction. That’s why how you communicate matters.

“To be as calm as possible so that a conversation is a discussion, not an argument. It must be simple, not go on too long because otherwise you will lose them… and then you can start to have a beautiful discussion, because they will feel unthreatened.”

Intervention is never too late in the teen years

Although Dr Evertsz’s early work involved helping teens in crisis, she became increasingly interested in intercepting issues before they spiral.

“By the time these young people arrive in those settings, things have become so complex that it’s very hard to intervene effectively,” she says.

“That experience made me very alert to risk signs… and very aware of the influence of people’s environments upon them.”

She believes though that adolescence is still a powerful opportunity to make change, especially at home.

“It’s a very effective time to intervene. And it’s important to intervene with the whole family, not just with the child, because they can’t change the environment that’s around them, which often plays a big role in feeding some issues.”

“Be Good” is no strategy

A common pitfall, Dr Evertsz singles out is the phrase from parents: “Be good” or “Behave yourself.”

“It’s conveys absolutely no information about what you’d like to see in a young person,” she says.

Instead, she says best to use something specific and relational like, “‘I’d really appreciate it at grandma’s today if you could say hello to them and have a little chat, sit for a little while with them… then no one will mind if you disappear after that.'”

Opposing styles of parenting and the real problem in between

Dr Evertsz says that being overly soft versus authoritarian can be damaging.

The soft approach she says, “doesn’t teach any coping mechanisms”.

“The child feels that they can always be rescued and they don’t need to have any personal input into a situation. Everything is done for them,”

On the other hand being overly “authoritarian” doesn’t teach anything apart from learning to keep very quiet and away from trouble.

“It doesn’t teach any skills, emotional intelligence. Instead it provides a climate of fear and hostility, which is very sad,” Dr Evertsz.

Even more common is a mismatch of these styles by parents, soft and hard.

“We’ve all come from different family styles ourselves, and so we may have quite ingrained beliefs about what is the best thing for our children.”

In these cases the child sits in the middle, not really benefiting from what the parents could offer.

“But if they [parents] can agree on as much as possible of what they don’t want to do anymore, and be there to support each other, they can still make a difference down the line.”

The truth is that both the parent and the teenager crave a close relationship. They don’t want to be alienated from each other, and they don’t really want that level of conflict. That’s a big desire underneath that most people really have, she says.

When the peer group is the risk

In situations, where the family relationship is fractured, outcomes can become dangerously unpredictable.

Dr Evertsz says it can all become “the luck of the draw”.

“You hear about many people who’ve come from very tricky backgrounds and have managed to do very well, but it’s a huge risk factor,” she says.

“Nothing’s guaranteed for a teenager – they can’t control very much in their lives, and since their peer group is so important… if their peer group is a toxic or dangerous one, then you’re in very difficult territory.”

Dr Evertsz encourages families to seek multiple forms of support when there’s a whole collection of things going on. Whether it’s school counsellors, mentors, or even specialised learning adjustments, when undiagnosed learning difficulties are behind their child’s difficult behaviour. “Sometimes the parents can’t manage it all on their own.”

Culture, connection and community

In her introduction to her book, Dr Evertsz points out a sobering reality, Australia has some of the highest youth suicide rates in the world, especially among young men.

In contrast, Greece has some of the lowest suicide rates in the world.

“We’re not sure why” Dr Evertsz says, and adds, “we can have suspicions”.

“The strength and the breadth of family support is a reason, and the different male culture in the country.”

She links risks to Australia’s “hyper-masculinism” and stigma around emotional expression, which men’s organisations are working hard to shift.

For many migrant families in Australia, the absence of extended family networks can leave a significant gap. Dr Evertsz stresses the importance of rebuilding those intergenerational connections through community.

“If you’ve got a migrant family arriving and they’re isolated, then the children won’t experience what they would have back home, which is regular contact with people of all ages.”

“The Greek community in Melbourne and Australia is active. There’s lots of resources, lots of activities, lots of people,” she says.

Communities like these, with strong intergenerational ties, can mirror the protective benefits of a large extended family, offering young people in migrant settings the stability, connection, and emotional support they might otherwise miss.

If we could redesign the teenage years of today

If we could redesign teenage years what could one change? is a common refrain.

Dr Evertsz calls for “more discussion at schools with the students acting as leaders; lots of outdoor time and physical activity”.

She says that teens need to do things with their peers without adult supervision.

She wants to see more “joy” in teens’ lives and “adrenaline highs” by activities that are social, like team and individual sports, adventure walks and volunteering.

“I think volunteering should be embedded in the lives of all children and teenagers.”

Dr Evertsz also calls for “regular get-togethers with people of all ages from the community that you value the most, is essential.”

With everything that’s expected of parents today, we ask her to define the core role.

“As parents we have many different roles and tasks – a good role is to be the person who sets the tone and standard for communication and problem-solving in the family.

Dr Evertsz calls for moderation, fairness and listening for parents.

“Parents who show interest in the other person even when things are tricky, will always be appreciated.”